Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

13 May, 2022

Talks among U.S. lawmakers on a potential bipartisan energy and climate bill have included a possible fee on carbon-intensive products entering the U.S.

Such a tariff could cut emissions globally and make domestic manufacturers more competitive against less carbon-efficient companies abroad. The consideration also comes as the European Union is working to implement a planned carbon border adjustment mechanism.

But talks of adding the proposal to a bipartisan bill are in the early stages, and implementation details have not been established.

In late April, U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., began consulting with both Republican and Democratic lawmakers on forming a possible bipartisan energy and climate bill. The talks started amid a stalemate over the broader Build Back Better social spending and climate legislation, which Manchin has opposed due to its total cost and objections to some family-focused support programs.

The bipartisan negotiations have considered including some climate provisions of the Build Back Better bill, such as tax incentives for clean energy. Lawmakers could also mull reforms to ease the development of natural gas infrastructure as a means to supply more LNG to Europe in exchange for potential measures to curb methane emissions, the Bipartisan Policy Center's Sasha Mackler said in a recent interview.

Carbon import fee in play

One of the participants in the meeting has been U.S. Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., co-chair of the Senate's Climate Solutions Caucus. A spokesperson for Coons confirmed in early May that a border carbon adjustment has been part of the talks but did not provide further details.

In July 2021, Coons proposed a bill to impose a "polluter import fee" on certain carbon-intensive products entering the U.S. The federal government would calculate the fee by averaging expenses for covered companies to comply with any "federal, state, regional, or local law, regulation, policy or program" designed to limit or reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The fee would initially apply to goods such as aluminum, cement, iron, steel, natural gas, petroleum and coal before expanding to other types of imports. Revenues from the fee would support technologies to reduce emissions and help workers and businesses affected by the clean energy transition.

Climate and trade

Conversations around a bipartisan energy bill — and a carbon import fee specifically — are preliminary. But "a growing number of members on both sides of the aisle are seeing the opportunities that exist at this nexus of climate and trade policy," said Greg Bertelsen, CEO of the Climate Leadership Council. The council is a bipartisan group that advocates for a carbon fee and dividends policy.

"A massive amount of emissions are traded internationally," Bertelsen said in an interview. "If we can put market incentives in at borders to encourage lower emissions, that's going to have a meaningful impact on climate change."

With the U.S. lacking a national carbon price, Bertelsen said the government could establish a benchmark for the carbon intensity of goods covered under the program and assess fees on imports if their carbon density exceeds domestically made alternatives. If imports to the U.S. matched the carbon intensity of more efficiently produced domestic goods, emissions would fall by 600 million metric tons annually, according to Bertelsen.

Partnering with allies would increase those environmental benefits. If the U.S. joined the EU, U.K., Canada and Japan and each country's imports matched their average domestic emissions intensity, global emissions would decrease by 1.8 billion metric tons per year, Bertelsen said.

The U.S. steel industry would be particularly well-advantaged under such a program. Steel is one of the most carbon-intensive industries, but U.S. producers are among the world's most efficient.

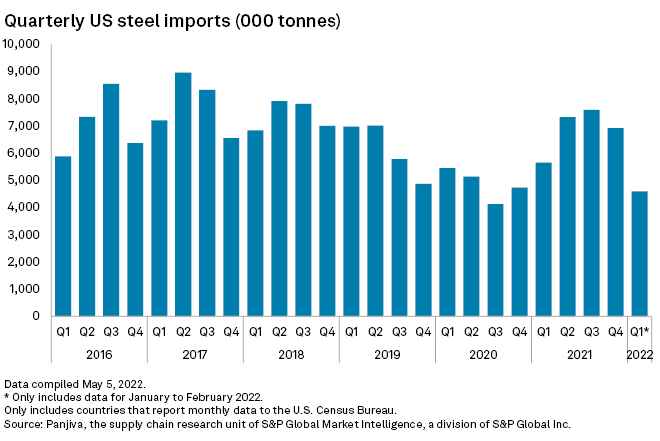

In 2019, U.S. steel production had the second-lowest average carbon intensity by country, according to a report released in April by Global Efficiency Intelligence, a Florida-headquartered consulting firm. But the U.S. is also a large steel importer, meaning much of what the country uses comes from more polluting sources.

"I think steel is probably going to be the first product area where [a carbon import fee is] going to apply because it is so widely traded and there is a lot of data," Kevin Dempsey, president and CEO of the American Iron and Steel Institute, said in an interview. "The U.S. industry has a carbon advantage, and we think it's important for that to be recognized."

While campaigning for the White House, U.S. President Joe Biden endorsed carbon adjustment fees or quotas for countries that fail to meet their climate change obligations.

But the administration never fleshed out a strategy for doing so. Furthermore, the U.S. could face challenges over the tariff before the World Trade Organization, whose rules make it difficult for countries to restrict trade. Consumers of U.S. steel imports could also push back against the proposal over cost concerns, particularly as inflation has rocked supply chains.

Meanwhile, the fee's ability to target imports from less efficient competitors could appeal to both Republicans and Democrats in Congress.

"There is an increasing recognition by members of both parties that dealing with this trade aspect is a key part of any effective energy and climate policy," Dempsey said.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.