Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

10 Nov, 2021

|

|

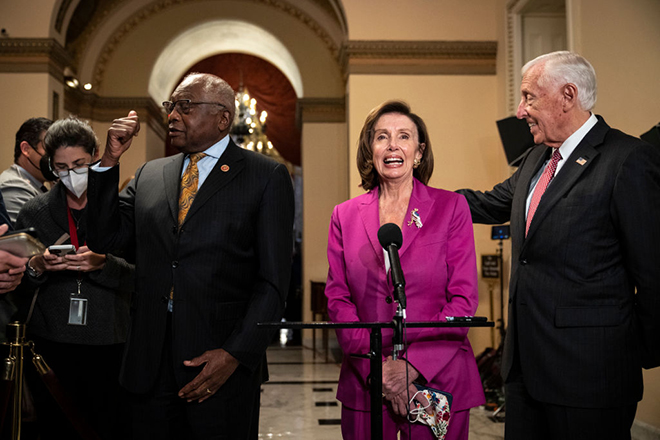

From left to right: House Majority Whip Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and House Majority Leader Rep. Steny Hoyer, D-Md., speak to reporters on their way to the House Chamber at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., on Nov. 5. The House passed the $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill after months of negotiations. |

The massive infrastructure bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on Nov. 5 could stimulate demand for domestically sourced materials through expanded "Buy America" requirements, but the country will not be able to supply all of the metal it needs to build the projects funded in the $1.2 trillion bill.

Dubbed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the legislation is expected to jolt demand for industrial metals and battery materials as the country pumps funding into everything from solar panels and electric vehicle charging stations, to roads, bridges and public transportation. That includes injecting $65 billion into the nation's power infrastructure. The Senate voted in favor of the bill in August, and U.S. President Joe Biden said he intends to sign the legislation soon.

Nestled in the roughly 2,700-page bill is a suite of provisions aimed at bolstering U.S. competitiveness by taking more control of supply chains. But those programs will take time to bear fruit. In the meantime, the U.S. will gradually become a very large buyer of industrial metals and battery materials at a moment when steel, iron ore, copper, lithium and several other metals are already in tight supply.

"In general, the U.S. has been playing catch-up in supply chains," said Andrew Leyland, head of strategic advisory at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, specializing in lithium-ion battery supply chains. "The U.S. cannot rest on its laurels when it comes to attracting their supply chain. This bill from the federal government is the first step in doing that I think. But what's really lacking in the U.S. is the upstream supply chain. That's effectively the [battery] cathode and anode production, the chemical processing and then the mining of the raw materials."

Running at capacity

The Biden administration has set reinvigorating U.S. supply chains as a top goal since inauguration. The infrastructure bill's success will depend in part on the country's ability to expand its domestic manufacturing of industrial metals such as steel at a time when the U.S. is already well into its economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and major steel companies are operating near full capacity.

Steel demand could increase by an estimated 5 million tons, roughly 5% of annual U.S. steel production, for every $100 billion in infrastructure spending, according to the American Iron and Steel Institute. And about 50,000 tons of steel would be needed for every $1 billion of infrastructure investment.

"Oftentimes, when we think about something like an infrastructure bill, the idea is that it would backfill demand that had disappeared from the private sector because of a reduction in broader economic demand," Moody's Investors Service analyst Ben Nelson said in an interview. "At this point, the recovery is well underway, so metals are actually tight and prices are very high."

Contractors rebuilding highways and bridges or establishing a network of electric vehicle charging stations, among other ambitious infrastructure projects in the U.S., will still rely on imports of materials such as steel.

"[The U.S.] is already not meeting our internal need for steel," Nelson said. "We buy it from other places. So to the extent the need increases, without capacity expansions, the industry is already running really hard."

The National Mining Association, which represents U.S. mining interests in Washington, D.C., called on the administration to take additional action to support the mining of high-demand metals and materials within the country.

"Mined materials are the building blocks of our nation's roads and bridges, power plants and water treatment facilities, transmission lines and charging stations," Rich Nolan, president and CEO of the National Mining Association, said in an emailed statement. "While much more work needs to be done to support domestic mining, we are grateful to members of both parties who championed these important provisions."

Boosting the critical mineral supply chain

"We will get America off the sidelines on manufacturing solar panels, wind farms, batteries and electric vehicles to grow these supply chains, reward companies for paying good wages and for sourcing their materials from here in the United States and allow us to export these products and technologies to the world," Biden said in a Nov. 6 statement.

Biden's infrastructure package authorizes the U.S. Energy Department to dole out $6 billion in funding through new loan and grant programs aimed at advancing battery material processing, as well as battery manufacturing and recycling. The bill also codifies an initiative within the U.S. Geological Survey to collect critical mineral resource location data and support an energy and minerals research facility, including testing a "full-scale integrated rare earth element extraction and separation facility and refinery." Furthermore, a part of the act sets out to make the nation's labyrinth of permitting processes more efficient to support critical mineral mining projects on federal land, including streamlining the environmental assessments and environmental impact statements required under the National Environmental Policy Act.

But the U.S. has a long way to go beyond the infrastructure bill if it wants to be a major player in battery markets, analysts said.

"I expect these subsidies, grants and the loan support to increase incrementally as the industry grows," Leyland said. "You can expect more funding for these types of programs as we move forward. I'd say it helps. It's not a game-changer on its own, partly because private industry still needs to finance most of this in the U.S. and partly because the [battery metals] industry is still relatively small."

It will also take time to see if the bill's investment in grants and research will translate into concrete manufacturing activity in the U.S. or if companies will continue to rely on metal imports, explained Ian Lange, an economist at the Colorado School of Mines and a former economic advisor for the Trump and Biden administrations.

The lack of upstream and midstream infrastructure in the U.S. means critical minerals are often mined beyond the country's borders and undergo various chemical processes — such as concentrating, refining and smelting — in China. China has a firm grip on the processing of several critical minerals and is also the epicenter for battery anode, cathode and electrolyte production. The U.S. lags far behind in capacity.

"The research and development, that's always easy to do, to pass or put into bill, but trying to find out what that actually does is hard," Lange said. "It's hard to see what's to be gained from some of those things."