S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

15 Apr, 2021

By Yannic Rack

| The open pit lignite mine and coal-fired power plant complex at Bełchatów, central Poland. |

.

|

Bełchatów Power Plant, located near its namesake town in central Poland, about 100 miles southeast of Warsaw, is a structure of superlatives. Run by Poland's largest electricity company, PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna SA, the roughly 5,000-MW behemoth is the largest coal-fired power station in Europe's most coal-addicted major economy and the single largest CO2 emitter on the continent.

PGE had once pledged to secure Bełchatów's operations well into the next decade, but that now looks uncertain. The company recently abandoned plans for a new lignite mine at the site, as it follows in the footsteps — albeit belatedly — of nearly every other major utility in Europe in pivoting away from fossil fuels and shooting for net-zero emissions by 2050.

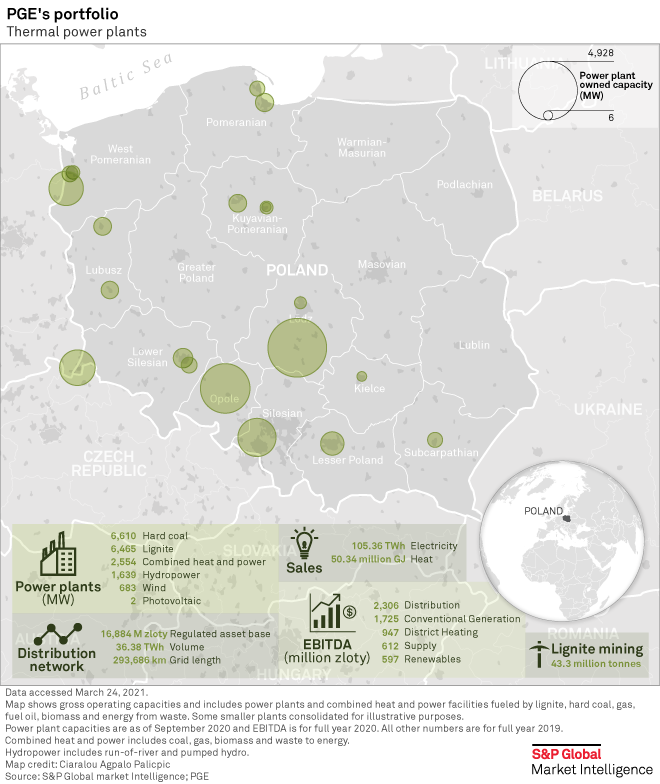

But the company faces a tough task. Poland still produces roughly three-quarters of its electricity from coal, and state-controlled PGE, like no other major utility in Europe, relies on hard coal and its dirtier cousin, lignite, to run its operations. In 2020, 86% of the group's power was produced from coal and 45% of its EBITDA came from conventional generation and district heating, which also includes natural gas and some other fuels.

That business model has rapidly become unsustainable as carbon prices rise and investors ditch coal-heavy assets from their portfolios, a reality that recently led PGE to abandon the new mine at Bełchatów.

"The development of new deposits would be absolutely unprofitable under current regulatory and market conditions, especially because of the CO2 prices," said Paweł Strączyński, until recently the company's CFO, referring to the EU's cap-and-trade emissions market. "With €42 [per tonne], you can absolutely forget about any new investments."

The company has depreciated its conventional power plants by more than 8 billion zlotys over the past two years. Its EBITDA dropped to 5.97 billion zlotys in 2020, down from 7.14 billion zlotys in 2019, due in part to deteriorating margins in its power plants.

Carving out coal

To adjust to this new reality, PGE is betting on a jumpstart. Prodded by the company, the Polish government is now deliberating over a plan to split off the mines and coal-fired power plants owned by PGE and its smaller state-controlled competitors into a fully state-owned entity that would manage their phaseout over the coming decades.

The Polish government owns just over 57% of PGE, but the company says its net-zero strategy has also been informed by conversations with institutional shareholders involved in the Climate Action 100+ initiative, including the investment arms of Italian insurer Assicurazioni Generali SpA and the Church of England.

Executives at PGE paint the spinoff proposal, which is expected in the coming months, as a make-or-break moment for the utility's future as it tries to raise money to finance its growth in low-carbon alternatives such as wind and solar power. The EU's green taxonomy, a new guide for investors to assess sustainable projects, is expected to further tighten financing for companies dependent on fossil fuels.

"The process of carve-out is absolutely necessary for us to realize our strategy," Strączyński said. "With coal assets in our portfolio, we will have definitely less chance to find cheap and secure financing for our green investments."

S&P Global Market Intelligence interviewed Strączyński in March, before he abruptly resigned from PGE and was appointed CEO of Tauron Polska Energia SA, one of PGE's competitors. PGE said it stood by Strączyński's comments and that the company's strategy had not changed.

A PGE spokesperson said the former CFO's move in fact suggests that "the transformation plans of Polish utilities are on the right track." Government ministers have said that if the EU approves the coal spinoff, it could be followed by a merger of PGE, Tauron and Enea SA to create a stronger Polish power player. That would mirror a model of consolidation already pursued by Poland's oil and gas industry.

Path to net-zero

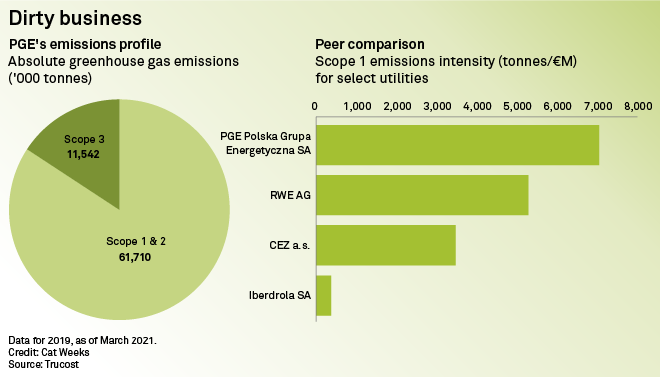

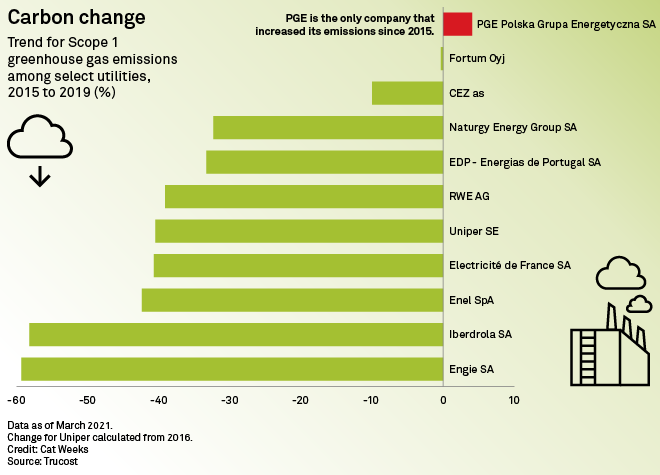

PGE was the only major utility in Europe to increase its direct emissions between 2015 and 2019, according to data from Trucost, and it has the highest emissions intensity per revenue out of its peer group.

The company has now pledged to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and wants to cut the bulk of its CO2 output by the end of this decade, although its strategy rests heavily on the state-sponsored coal spinoff.

Even then, its portfolio will still rely heavily on hard coal and natural gas, which is less polluting but still emits CO2. And the company's climate targets do not even include the Scope 3 emissions created by PGE's customers or in its supply chain.

The company says some of its coal-fired combined heat-and-power plants, which are not part of the spinoff plan, could still be online in 2030. It plans to eventually replace the coal and gas in those plants with zero-emission gas, such as hydrogen produced with renewable energy, or even small modular nuclear reactors.

"Gas will be an absolutely necessary transition fuel, especially for district heating," Strączyński said. "In the 2040s, however, we already assume that natural gas will become a thing of the past."

By 2030, PGE also wants to increase the share of renewable energy in its portfolio to 50%. The company owns a small portfolio of onshore wind parks and wants to build 1,000 MW of additional capacity by the end of the decade, alongside at least 3,000 MW of solar photovoltaic plants.

Its flagship initiative, however, is a pair of offshore wind parks in the Baltic Sea, which the company is developing with industry leader Ørsted A/S. The joint venture was awarded 25-year subsidy contracts for the two plants on April 7. PGE also wants to spend more money to strengthen its power grids and build out its retail offering.

The utility says it can finance a quarter of the 75 billion zlotys investment to reach its 2030 targets with EU funding. It has already applied for two dozen projects under Poland's national coronavirus recovery plan, which the country will submit to the EU in order to get access to the bloc's €672.5 billion stimulus package.

Another quarter of the required investments will be PGE equity, with the rest from banks and investors.

'The last investment'

Strączyński said it would be "absolutely crazy" to pull the plug on the new unit now, just before it is supposed to come online. But as things stand, the project will mark the last time PGE spends money on either Bełchatów or Turów — maintenance aside.

"It is absolutely the last investment for us in the lignite sector," Strączyński said.

For environmental campaigners, that is not good enough. Greenpeace has sued PGE, demanding that the company stops any further fossil fuel investments and reaches net-zero emissions at its existing coal plants by 2030 at the latest.

"They're pursuing coal assets while asking the government to bail them out," said Joanna Flisowska, head of the climate and energy unit at Greenpeace Poland, referring to the proposed coal spinoff, which she said merely gives PGE "an excuse to do nothing."

The Czech Republic is also suing Poland over extending PGE's mining license at Turów until 2026. It says the mine is having negative environmental impacts, including reducing drinking water supply across the border, and wants PGE to shut it down. The company says this would spell economic disaster for the region and fly in the face of a just transition out of coal.

In fact, PGE wants to extend its mining license in Turów until 2044 to supply fuel for the power plant's new unit. In Strączyński's view, part of Poland's coal plants will likely be needed until 2049, the eve of the EU's net-zero target. But Poland was the only country not to sign up to the bloc's climate goal, and government ministers suggested as recently as last year that some coal power plants could stick around until 2060.

"The coal assets will be necessary for the Polish energy sector for many, many, many years more," Strączyński said. While PGE will not put any more money into the fuel, he said the state could of course decide something else.

As of April 14, US$1 was equivalent to 3.80 Polish zlotys.

Trucost is part of S&P Global Market Intelligence.