Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

4 Mar, 2021

By Sanne Wass

Amid news of investors suspending funding to Greensill Capital (UK) Ltd., industry players fear it could cause a ripple effect on the supply chain finance market as a whole, to the detriment of small businesses in need of liquidity now more than ever.

While supply chain finance has faced controversy around its accounting treatment and usage, the technique itself is not to blame for Greensill's problems, they said.

Greensill is reportedly preparing for insolvency after Credit Suisse Group's fund management arm and Swiss asset manager GAM Holding AG this week announced they had frozen funds linked to the U.K.-based lender.

For other supply chain finance players, this is "really bad timing," with the market already dealing with reputational issues and the coronavirus pandemic, said Erik Hofmann, a professor at the Institute of Supply Chain Management of the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland.

The Greensill case could trigger "a fatal loss of confidence" in supply chain finance, potentially starting a "domino effect" of investors withdrawing funding, Hofmann said in an interview.

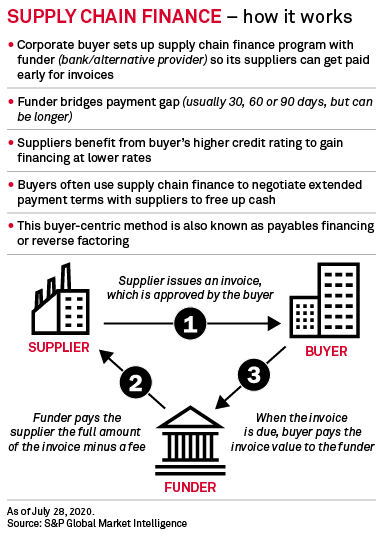

Supply chain finance comprises various financing tools, but the term is commonly used to describe what is also known as reverse factoring, a technique in which a corporate buyer partners with a bank or alternative provider to allow suppliers to be paid early for their invoices.

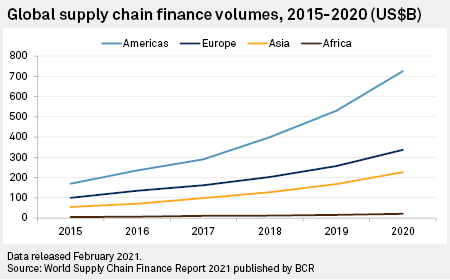

The market has grown significantly in recent years, to a total value of $1.31 trillion in 2020, according to the latest World Supply Chain Finance Report, published by intelligence company BCR last month. In 2020 alone, supply chain finance volumes grew 35%.

Reputational challenges

While banks remain the largest lenders in this space, Greensill, as an alternative provider, has played an important role in bringing the asset class to private investors. The company arranges supply chain finance programs directly with corporates, then packages and sells the assets to investors through funds.

Just last month, Bloomberg heralded Lex Greensill, the company's founder, as "the king of supply chain finance."

"Greensill really did put this technique on the map. They deserve kudos for that," said Tony Brown, CEO of The Trade Advisory, a trade finance consultancy, in an interview.

But with Greensill now in financial trouble, Brown said it could prompt investors to question supply chain finance as an instrument.

|

"When something like this happens, it deflates the enthusiasm that ordinarily should exist for this technique. I worry that it will scare off some investors who otherwise should be attracted to the space," he said.

Supply chain finance has already come under fire in recent years, criticized for being used by some companies to push their suppliers to accept unusually long payment terms. Furthermore, because it is recorded in the corporate's accounts as "trade payables" rather than financial debt, credit rating agencies have warned it could hide a company's true financial leverage.

In past instances, companies have extended payment terms to suppliers up to almost a full year, creating a significant working capital benefit "without any recognition of borrowings," according to an S&P Global Ratings report published last year.

Fitch Ratings has claimed that this "classification loophole" was a "key contributor" to the liquidation of British construction giant Carillion in 2018 because it veiled some of its financial challenges.

The supply chain finance industry undoubtedly faces structural problems it needs to address, both around the instrument's accounting treatment and ethical questions on how companies should be using it, said Hofmann. But these particular issues are not connected to Greensill's current difficulties, Hofmann said.

The driving force behind Credit Suisse's funding suspension relates to concerns about Greensill's exposure to a single client, the U.K.-based steel magnate Sanjeev Gupta, The Wall Street Journal reported. Lapsing insurance policies, which give investors comfort that their money is safe, was supposedly another factor.

"There are so many good things about supply chain finance," said Steven van der Hooft, CEO of supply chain finance consultancy Capital Chains, in an interview.

This form of finance is particularly valuable for small and medium-sized enterprises as it gives them access to funding that may have otherwise been unavailable to them, and at more affordable rates because the cost is based on their buyer's credit rating. Supply chain finance will be crucial to helping these companies restart their activities as economies reopen after the pandemic, van der Hooft said, expecting an "immense need" for the product in the coming year.

Van der Hooft, too, argues that the supply chain finance product itself is not to blame for the problems at Greensill, but he is worried that the instrument will face further criticism following recent developments. A potential ripple effect could cause liquidity to dry up in similar programs and leave suppliers, particularly SMEs, without access to funding, van der Hooft said.

Economic crisis ahead

The coronavirus pandemic and its economic aftermath could further add fuel to the fire. Hofmann said government support measures are currently providing a "protective shield" for many companies, and the scaling back of such efforts is likely to lead to more insolvencies.

This not only poses a risk of losses within supply chain finance, but is likely to also impact the risk appetite of credit insurers, Hofmann said, adding another hurdle for supply chain finance schemes relying on credit insurance as protection against default.