Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

23 Sep, 2021

By Sanne Wass

The higher price that investors pay for green bonds on the primary market is justified by the instruments' strong performance and flexibility on the secondary market, according to industry players and new research.

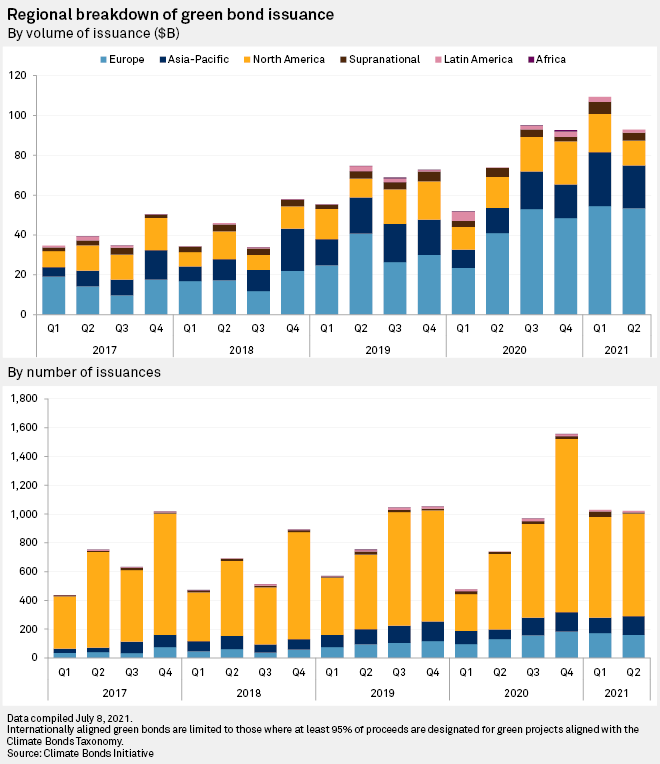

The supply of green bonds reached a record high in 2021, with companies globally issuing more than $200 billion worth of such debt in the first half of the year. The Climate Bonds Initiative, or CBI, found that the premium on green bonds, also referred to as the "greenium," is evident globally and is particularly strong for U.S. dollar debt. Savings for borrowers range between 1 basis point and 10 bps on a global basis, according to ING.

Although this means investors on average pay a higher price for green bonds in the primary market, continued high demand for the instrument means the greenium has typically expanded in secondary trading, Erik Bennike, head of credit at Danish pension fund PensionDanmark, told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"We justify the greenium and still buying into the green bonds by using a simple economist argument," said Bennike, speaking on the matter at the CBI 2021 conference Sept. 7. "The demand currently vastly outpaces the supply in this area. And if you don't have an expectation for that to change materially, then buying stuff that is expensive, but has the potential to be even more expensive, still makes sense."

The perception of inferior investment returns is the greatest barrier to investing in green bonds, according to 44% of 231 institutional investors polled by NN Investment Partners earlier this year.

Tradeweb, an electronic trading platform, has also tracked an expanding greenium in the secondary market, said Simon Maisey, the company's global head of corporate development, in an interview. The performance of green and non-green bonds issued by the German government is the easiest way to measure such a greenium, he said, given Germany pairs new green issuance with a vanilla twin that shares similar characteristics.

Last year, the German government issued two green bonds, each partnered with vanilla equivalents. On a 10-year bond issued in September 2020, the yield difference from its vanilla twin has risen to close to 7 bps in recent months, from an initial 1.5 bps, while on a five-year bond issued in November, this number has increased to almost 5 bps, from an initial 1 bps, according to Tradeweb.

The CBI's research, which also recorded strong performance of green bonds in the immediate secondary market, found that green bonds come with superior liquidity, while yield volatility tends to be lower.

"Even in a crisis, you could always find a buyer for a green bond," Caroline Harrison, senior research analyst at the CBI, said in an interview. "And that's the time when investors need to fund redemptions; maybe they've got people pulling money out of their funds and they need to be able to repay and things like that. So at that point, it is crucial really to have that flexibility as an investor."

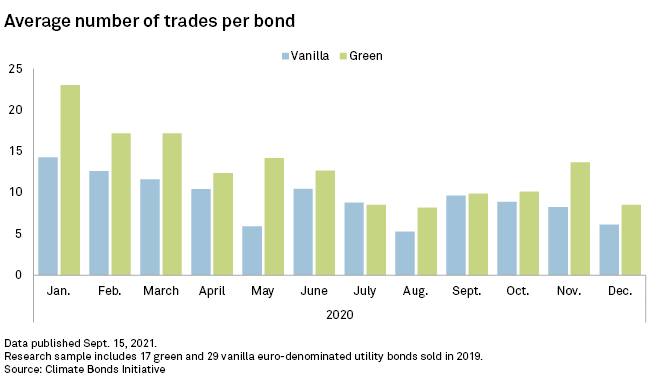

On average, green bonds in the CBI's sample of utility bonds traded more frequently than vanilla equivalents in 11 out of 12 months in 2020. In March 2020, when capital markets were hit by the pandemic, the research recorded 48% more green bond trades than vanilla. The largest difference was in May 2020, when green bonds traded 2.4 times more frequently, it found.

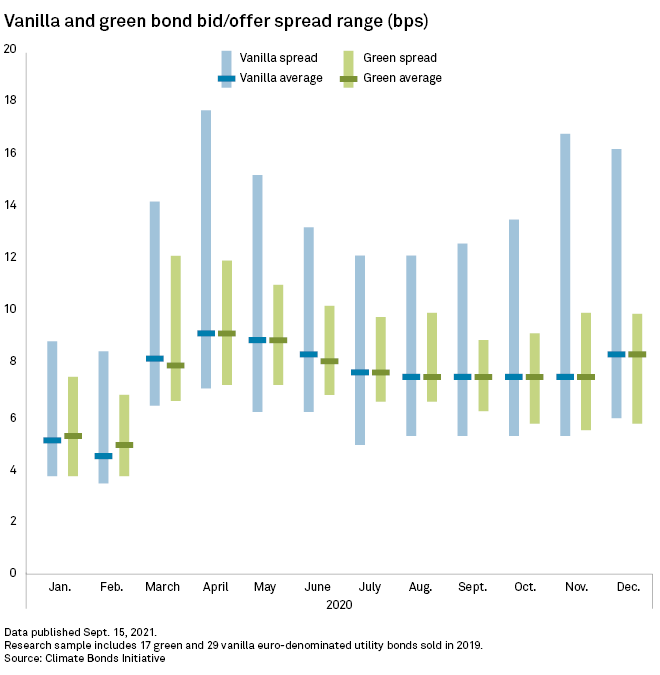

Furthermore, the average bid/offer spread, the difference between the highest price that a buyer is willing to pay and the lowest price that a seller is willing to accept, and a measure of market liquidity, was narrower for green bonds every month in 2020, suggesting a greater number of buyers and sellers.

The future of the greenium

Whether this greenium will persist has caused some disagreement among market participants and observers.

"There is not much to suggest that greenium is getting smaller, because there is such a massive demand for these products, especially from a large number of specialized investment strategies and funds. Even though supply is increasing, it takes some time before it catches up to the demand there is at the moment," said PensionDanmark's Bennike.

At the CBI conference, he suggested it could take years before green bonds are to converge in pricing compared with traditional bonds.

Others are less convinced of the long-lasting greenium on green bonds, with Sebastian Zank, deputy head of corporate ratings at Scope Ratings, expecting it to disappear this year.

The pricing difference between green and non-green bonds has so far been driven by "over-demand" for the instrument, Zank said in an interview, adding that growth in supply and better familiarity with green bonds are enabling investors to be more critical and selective.

"The investors will return to the driver seat," Zank said.

While green bonds are still gaining more interest from investors than non-green bonds, the attraction is getting smaller, with average oversubscription on green euro-denominated bonds falling to 2.9x in the first half of 2021 from 4.2x in the previous six-month period, according to the CBI.

When looking at the risk profile for green versus vanilla bonds, there is "absolutely no justification for a lower pricing for green bonds and the like," Zank said.

"One should never assume that just the green paint is mitigating risks," he said. What will ultimately matter is whether a green project is helping to improve future cash flows, which not all may be doing. In fact, some environmental, social and governance-labeled bonds could cause a deterioration of credit metrics if they require investments that are not counterbalanced by cash inflows, Zank said.