Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

6 Jul, 2022

By Siri Hedreen

| A regional hydrogen hub would include a transportation network anchored by a hydrogen production plant, like the one in Fort McMurray, Alberta, above. |

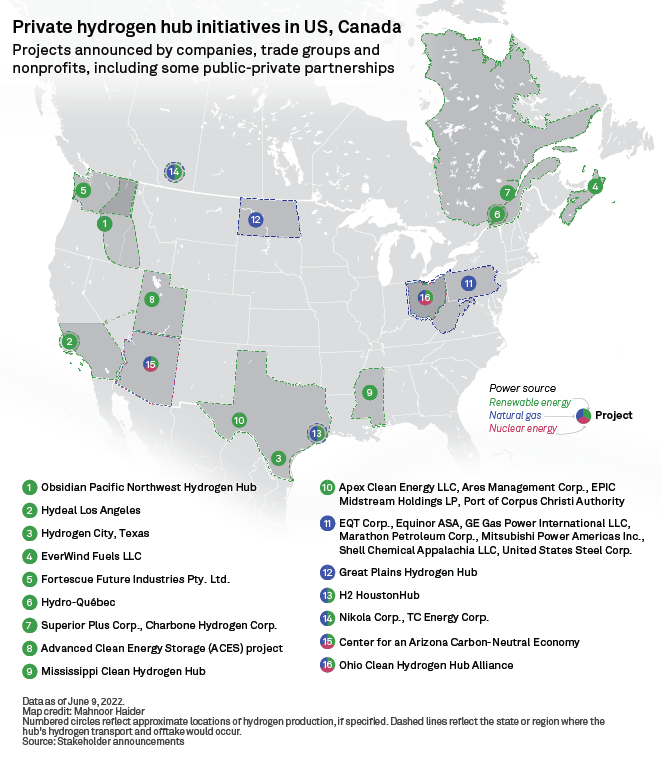

The U.S. government's multibillion-dollar effort to spur a national hydrogen economy has prompted developers to step forward with at least two dozen public- and private-sector hydrogen hub initiatives to date.

Before federal funding was available, Obsidian Renewables LLC had already started planning for its Obsidian Pacific Northwest Hydrogen Hub anchored by a green hydrogen production facility in Hermiston, Ore., powered by "behind-the-meter" wind and solar. Now the Oregon-headquartered renewable energy developer hopes to join forces with proponents of other hydrogen projects to pitch a Pacific Northwest hub to the U.S. Energy Department.

In 2021, the U.S. bipartisan infrastructure law committed $9.5 billion in federal funding for "clean" hydrogen, including $8 billion for the development of at least four regional hydrogen hubs, $1 billion to reduce the costs of green hydrogen and $500 million for clean hydrogen recycling and manufacturing.

The "DOE has made very clear they don't want to see multiple proposals from specific regions. They don't want to deal with hundreds of proposals. They want big ones," said Ken Dragoon, director of hydrogen development at Obsidian. "One of the big challenges with these hydrogen hubs is, once the $8 billion notion was released, everybody and their brother has decided that they've got a hydrogen hub proposal."

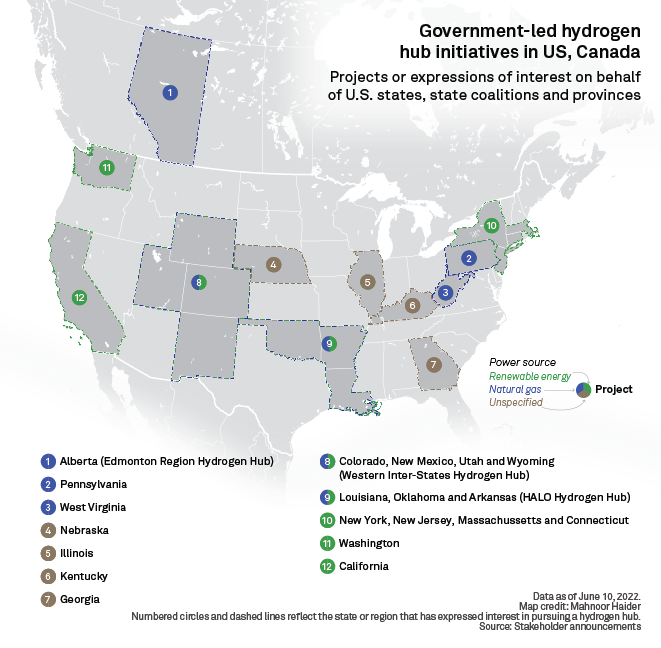

The Canadian government, meanwhile, projects hydrogen to deliver 30% of the country's end-use energy by 2050. The Canadian federal government has yet to float a specific dollar figure solely devoted to hydrogen. But multiple provinces have followed up with their own plans, including Alberta, the biggest hydrogen producer in the country, setting a goal of C$30 billion in capital investment to develop the clean-burning gas.

Variable carbon footprint

Hydrogen can be used to store and transport energy for a range of potential end uses, including heating, transportation, metals production, fertilizer and electric power generation. Some industry and policy experts have called hydrogen the "holy grail" for decarbonization because hydrogen produces only water when burned, unlike fossil fuels' carbon releases.

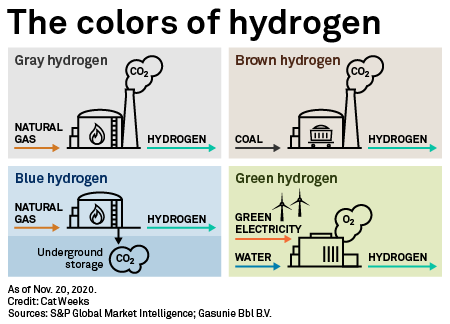

But hydrogen production can have a more variable carbon footprint, depending on the power source. Green hydrogen, powered by renewable energy, and pink hydrogen, powered by nuclear energy, are produced by electrolysis, or the separation of hydrogen and oxygen in a water molecule. But the zero-emission process is also the most expensive. Instead, about 95% of hydrogen worldwide is produced by steam reforming of natural gas, referred to as gray hydrogen.

Blue hydrogen is produced the same way as gray, but carbon dioxide emissions are mitigated using carbon capture and storage, a nascent technology that captures the greenhouse gas from smokestacks and pipes it underground.

The bipartisan infrastructure law requires the DOE to back at least one green, one pink and one blue hydrogen hub, and at least two hubs must be in natural gas-rich regions. Whether blue hydrogen should be considered clean hydrogen is a point of contention, and its inclusion in the DOE's plan has ruffled feathers. According to some environmental groups, carbon capture mitigates emissions from the production of hydrogen but not from the extraction and transport of the natural gas feedstock, and the technology has yet to be deployed at scale. Other stakeholders tout blue hydrogen as a low-emission "bridge" to a zero-emission economy.

Bidding wars

Many natural gas companies have welcomed the rise of hydrogen, both for the fuel's potential compatibility with existing natural gas infrastructure and for blue hydrogen's reliance on gas as a feedstock. This gives regions such as the Gulf Coast, the prairie states and Appalachia a leg up in the race to deploy hydrogen.

"The entire Gulf Coast region is ripe for this sort of development," said Brett Perlman, CEO of the Center for Houston's Future. In May, the community development nonprofit put out a 60-page report making the case for Houston as the epicenter of a global hydrogen economy. "While we're focused on Houston and Texas, ultimately, at the end of the day, we want this to grow into places along the Gulf Coast that mirror, if you will, where the infrastructure already exists."

Other initiatives — including the Great Plains Hydrogen Hub in North Dakota proposed by Mitsubishi Power Americas Inc. and Bakken Energy LLC, and the provincial government-backed Edmonton Region Hydrogen Hub in Alberta — also seek to capitalize on their own regions' natural gas economies. In addition to the existing pipeline networks, these regions come with further intangible assets.

For regions without that existing physical infrastructure, the focus has largely been on green hydrogen. In March, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul launched a massive coalition, joined by the governors of Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Jersey as well as dozens of industry and university partners, to pursue federal funding for a northeastern hydrogen hub powered by offshore wind and solar. The states of Washington and California have made similar declarations. In eastern Canada, several companies have announced their intent to produce hydrogen from wind and hydropower.

In some of these regions, natural gas-fueled hydrogen is either politically challenging or physically unfeasible — or both. "On the West Coast, there just isn't going to be blue hydrogen from natural gas. It just isn't acceptable," said Dragoon, pointing to decarbonization commitments in California, Oregon and Washington. "Now, proponents of blue hydrogen think they're going to capture the carbon and put it underground. Well, OK, maybe they'll do that. We don't really have anywhere to put it here in the Northwest."

CO2 captured from smokestacks must be piped, in liquefied form, to an underground well created by natural geologic structures. Not every region has the requisite geology.

With clean hydrogen yet to be proven at scale, proponents of some projects are taking a wait-and-see approach. In Arizona, four energy providers and three state universities, comprising the new Center for an Arizona Carbon-Neutral Economy, joined forces in May to pursue a regional hydrogen hub. The coalition expects to include in its hub proposal green, blue, pink and, potentially, turquoise hydrogen (produced from methane cracking to solid carbon and hydrogen), though nothing is set in stone, according to project member Ellen Stechel, co-director of Arizona State University's Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation.

The Arizona coalition's participants include major utilities Pinnacle West Capital Corp. subsidiary Arizona Public Service Co., the Salt River Project, Fortis Inc. subsidiary Tucson Electric Power Co. and Southwest Gas Holdings Inc.

In natural gas-abundant Ohio, blue hydrogen is the focus, but green and pink hydrogen are still on the table. "Our members recognize that a blend of multiple colors is the quickest path to success," said Michael Guastella, a spokesperson for the industry-led Ohio Clean Hydrogen Hub Alliance.

Shovel in the ground

Feedstock availability is a key consideration. But red tape is just as much a force to be reckoned with, according to energy developers.

"Uncertainty in permitting is a big driver for site selection for us," Dave Edwards, director and advocate for hydrogen energy at L'Air Liquide SA, said at a recent hydrogen hub panel hosted by Steptoe & Johnson LLP.

In May, the industrial gas producer opened its largest liquid hydrogen plant, in North Las Vegas, Nev., to provide hydrogen to mobility market customers in California. According to Edwards, the facility took about two years to permit — "quite rapid, by most industrial standards" — and another two years to construct. "The reason we're in Nevada is because we could do that in two years," Edwards said.

Some states, such as Texas, have what Dragoon called "drive-by permitting" policies that may give them an upper hand in becoming a first mover.

Developing a new energy infrastructure is "never easy, in any part of the country," Perlman said. "But we do have a climate in Texas where you can develop things. We don't have the same level of NIMBYism that exists in other parts of the country."

As such, when choosing a site, "the real driver isn't actually on the production side. It's almost always on the off-take side," Edwards said. "Where are your off-takers going to be? Do you have a primary customer? If there is a primary customer, where are they located, and in what form do they need the hydrogen?"

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.