S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

10 Jun, 2021

By Molly Christian and Zack Hale

The Biden administration's push for Congress to enact a national U.S. clean electricity standard, or CES, is pitting utilities with substantial natural gas-fired capacity against environmental groups that want the fuel excluded from potential clean power standards. Those tensions represent yet another hurdle to establishing a mandatory federal CES, a key piece of U.S. President Joe Biden's goal of decarbonizing the power sector by 2035.

Since the start of his presidency, Biden promoted the creation of a nationwide CES to help reach climate goals and made the policy part of the infrastructure-focused American Jobs Plan released in March. But major pieces of Biden's infrastructure plan need approval from Congress, and negotiations with lawmakers on the issue have grown increasingly fraught.

On June 8, infrastructure talks between Biden and leading U.S. Senate Republicans broke down, with GOP lawmakers consistently pushing for a smaller and more streamlined package focused on traditional projects, such as new or upgraded roads and bridges.

Democrats could try to move Biden's infrastructure plan through budget reconciliation, a process that allows legislation to pass with simple majorities in both chambers of Congress, but some climate hawks in Congress are questioning whether provisions such as a CES will make their way into an infrastructure bill.

"Climate has fallen out of the infrastructure discussion, as it took its bipartisanship detour. It may not return," Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., a member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, tweeted on June 7. "I don't see the preparatory work for a close Senate climate vote taking place in the administration," and Congress is "running out of time" to advance such legislation, Whitehouse added.

Meanwhile, U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., who chairs the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and is a key swing vote in the narrowly divided upper chamber, frustrated more liberal members of his party by seeking time to clinch a bipartisan compromise through regular order.

Manchin is working with several other senators on a bipartisan infrastructure proposal. Although the offer could include climate provisions, Manchin may be hesitant to back a CES proposal if he feels it is too punitive for fossil fuels, with the West Virginia lawmaker's home state a major coal and gas producer.

Gas tensions

Along with broader uncertainty over infrastructure legislation and the role of climate policy within it, divides have surfaced over how a potential CES should apply to natural gas-fired generation.

With gas currently fueling around 40% of U.S. electric output, most leading CES bills in Congress in recent years have made room for the energy source. Gas replaced a substantial amount of more carbon-intensive coal-fired capacity in the past decade and could incorporate carbon capture technologies to achieve little to no emissions.

"We can't forget the role of natural gas and what it plays in reducing emissions," Jennifer Loraine, managing director of public policy at Duke Energy Corp., said in an interview. "So a CES should recognize that by providing a permanent partial credit for [natural] gas."

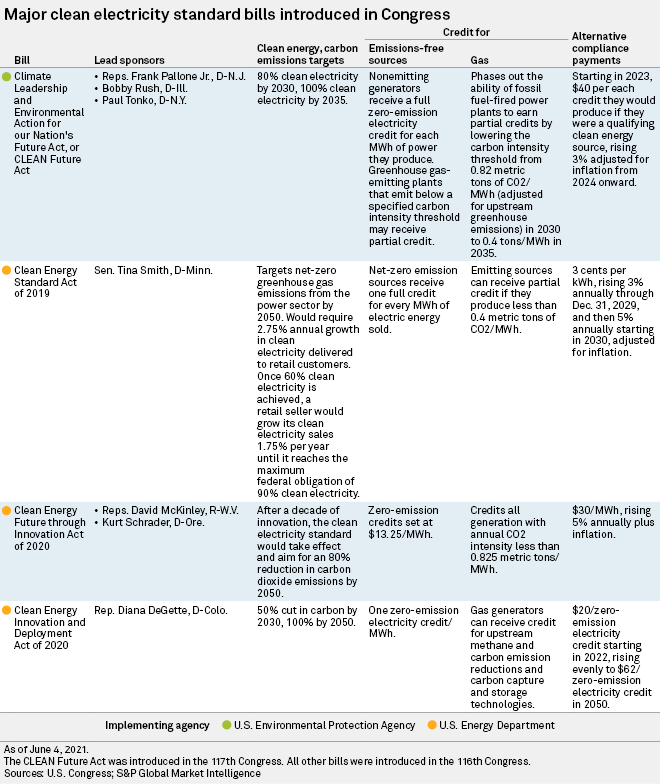

A broad climate bill that U.S. Rep. Frank Pallone, Jr., D-N.J., and other Democratic leaders of the House Energy and Commerce Committee introduced in March included a CES that aligns with Biden's goal for 100% emissions free-power by 2035.

The bill would initially allow natural gas-fired plants to receive partial clean electricity credits if they emit less than 0.82 metric tons of CO2 per MWh, adjusted for upstream greenhouse gas emissions. That threshold falls to 0.4 metric tons per MWh in 2035, meaning less gas generation would qualify for the CES over time.

But the lower 2035 limit still roughly equals emissions from a natural gas combined-cycle plant without carbon capture installed, said Abhoyjit Bhown, head of carbon capture research and development for the Electric Power Research Institute.

|

|

Other CES bills in Congress give similar credit to gas-fired plants and on more extended timelines.

American Electric Power Co. Inc. and Xcel Energy Inc. endorsed a CES bill introduced in 2020 by U.S. Rep. Diana DeGette, D-Colo., that aims for 100% clean power by 2050. The legislation would allow generators to receive zero-emissions credits for upstream methane and carbon emissions reductions, as well as carbon capture technologies.

American Electric Power also backed a bipartisan bill introduced in 2020 by U.S. Reps. Kurt Schrader, D-Ore., and David McKinley, R-W.Va. The bill, which targets an 80% cut in power sector carbon dioxide emissions by midcentury, would credit all generation with annual CO2 intensity below 0.825 metric tons per MWh.

In addition, U.S. Sen. Tina Smith's, D-Minn., CES proposal from 2019, which Xcel supports, would allow emitting sources to receive partial credit if they produce less than 0.4 metric tons of CO2 per MWh. Smith's bill would put the U.S. power sector on track for net-zero emissions by 2050.

Smith, McKinley and Schrader are expected to reintroduce their respective proposals this Congress. Spokespeople for DeGette did not respond to a request on when the Colorado lawmaker may repropose her bill.

"It is imperative that a CES encourages innovation and the development of new, dispatchable carbon-free resources that are available 24/7 in all weather conditions," Xcel spokesperson Julie Borgen said. "But it must also allow energy providers to maintain existing nuclear power plants and dispatchable generation like natural gas to ensure reliability and affordability until new technologies are commercially available."

In addition to the substantial amount of gas-fired generation already in operation, the U.S. is set to add nearly 60 GW of new gas-fueled capacity in 2021-2027, according to data compiled in February by S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Companies with the most planned new U.S. gas-fired capacity in 2021-2027 include FGE Power LLC, Ember Partners LP, NTE Energy, NextEra Energy Inc., and Emera Inc., Market Intelligence data shows.

Some green groups cry foul

Although most leading CES bills offer only partial credit to fossil fuel-based generation without carbon capture, some environmental groups think that is too much.

In a letter sent to congressional leaders in May, nearly 700 environmental and social justice groups, including Friends of the Earth and the Center for Biological Diversity, urged Congress to pass a 100% renewable energy standard. They deemed resources such as gas, nuclear energy and fossil fuel-fired plants with carbon capture "false solutions."

"Even a partial credit for fossil fuel resources that attempts to factor in lifecycle emissions runs the risk of subsidizing environmental harm for years to come," the letter stated. "Allowing dirty energy to be bundled with clean energy under a federal energy standard would prolong the existence of sacrifice zones around dirty energy investments and delay the transition to a system of 100 percent truly clean, renewable energy."

In a recent blog post, Friends of the Earth said fewer than 1% of gas-powered facilities would be excluded from receiving a partial credit during the first decade of the CES proposed in the House energy committee's broad climate bill. The group also said most gas plants would qualify for credits under a 0.4 metric ton per MWh carbon threshold.

The limit would only exclude most gas plants, the group predicted, if the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency "accurately and aggressively" measured methane leaks from natural gas infrastructure. But Friends of the Earth said the EPA has failed in the past to accurately measure lifecycle emissions for other fuels, raising doubts about its ability to do so for a CES.

"A lifeline for fracked gas and other false solutions is not better than nothing," said Lukas Ross, a program manager at Friends of the Earth. "If a clean energy standard like the one in Chairman Pallone's bill is included in the American Jobs Plan, progressive climate activists across the country will rise up and oppose the bill."

Reconciliation outlook

If Democrats get on the same page regarding infrastructure legislation, the reconciliation process could help them get around GOP resistance, particularly if Democrats include bold climate measures.

But adding a CES to an infrastructure-focused reconciliation bill would still be difficult. The CES would need to be structured to meet the reconciliation process's budgetary requirements, including that it change government spending or revenues by a certain amount.

"In Washington, there's a cottage industry that's grown up around trying to think about how something that functionally would be similar to a CES could move through budget reconciliation," said Conrad Schneider, advocacy director at the Clean Air Task Force. But Schneider noted that such a program would need to be narrowly crafted to comply with the Byrd Rule, which prohibits provisions deemed "extraneous" to the U.S. budget by the Senate parliamentarian.

With negotiations dragging into the summer, the desire for a deal could ultimately prompt Democrats and Republicans to coalesce around bipartisan legislation resembling the McKinley-Schrader bill, said Samuel Thernstrom, founder and CEO of the Energy Innovation Reform Project. Thernstrom, who is working to build support for McKinley-Schrader, noted that the bill would make major investments in technologies, such as long-duration energy storage and carbon capture, over its first decade before emissions reduction targets kick in.

"I think the list of members for whom it's their first choice is not long today," Thernstrom said in an interview. "But the list of members who are looking at [McKinley-Schrader] thinking, 'You know, I might not get my first choice, but this is something I could get,' I think is significant."

Jeff Holmstead, a former assistant administrator of the EPA's air office who now represents utilities at the law firm Bracewell LLP, said legislation that falls "in the middle" of McKinley-Schrader and DeGette's bill could have "a real shot."

"There are a lot of people in the business community who believe that would be good policy, and it would provide some regulatory certainty," Holmstead said.