Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

29 Apr, 2021

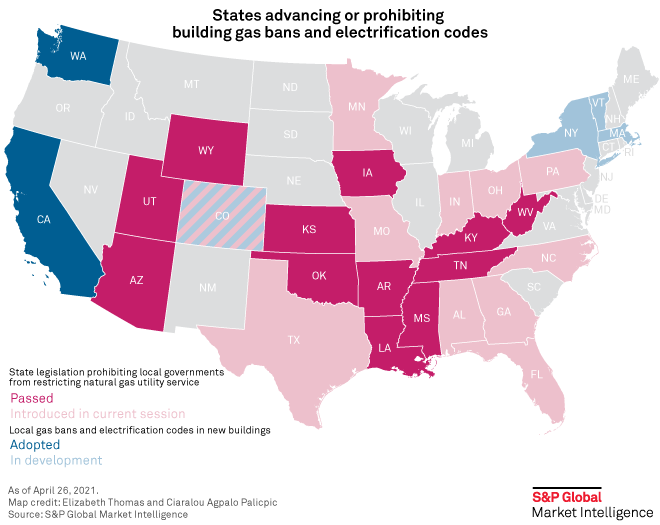

Burlington, Vt., has made swift progress toward joining the ranks of cities implementing policies to restrict natural gas use in new buildings. Meanwhile, roughly a quarter of U.S. states have now passed laws prohibiting building gas bans. Several more could soon follow suit, as climate activists grow concerned about the expanding scope of the so-called energy choice bills in some legislatures.

Burlington expands building electrification movement

Burlington is advancing a plan to encourage all-electric construction by levying a fee on carbon emissions from new buildings that choose to connect to natural gas infrastructure.

The city, the first in the U.S. to source 100% of its power from renewable sources, is seeking authority from the state legislature to implement an ordinance proposed in October 2020 and backed by voters in March. If Vermont lawmakers give Burlington the green light, it would put the state's most populous city on track to restricting gas use in new buildings.

Under the proposed ordinance, if a new building connects to fossil fuel infrastructure, the owner would pay a building carbon fee, equal to $100 per ton of the building's anticipated carbon emissions over its first 10 years of operation. The city would assess the fee at the start of each new decade of building operation. The ordinance would also require new buildings with gas hookups to be wired for conversion to electric heating systems and appliances. All-electric buildings would not face any additional requirements during the permitting process.

"It's an incentive up front to say, the more you can reduce your fossil fuel use, the less your building carbon fee would be, even if you can't get it to zero," Darren Springer, general manager of municipal utility Burlington Electric Department, said. "And then we wanted to be able to reassess it every 10 years to help drive continued progress towards reductions, as opposed to a one-time fee that would only impact decisions being made at construction."

Burlington Mayor Miro Weinberger announced the ordinance proposal on Oct. 6, 2020, following about a year of work to develop building decarbonization strategies by city staff and the Burlington Electric Department, with assistance from the Building Electrification Institute. However, lawyers for the city determined the city council needed charter authority from the state to assess a carbon fee.

The council voted in December to send a resolution to voters seeking an update to the city charter. Nearly 65% of Burlington voters supported the measure in a March 2 ballot. A group of state Democrats introduced House Bill 448 to approve the charter changes on April 14.

Meanwhile, Burlington is advancing a primary renewable heating ordinance, which could serve as a sort of failsafe should state lawmakers reject the charter amendment. Under the proposal, the city would require newly constructed buildings to have a primary heating system sized to meet roughly 85% of load from renewable sources. Since Burlington's electric supply is 100% renewable, using an electric heat pump would bring the building into compliance, Springer said. A building owner could also opt for a geothermal or advanced wood heating system or offset emissions through a renewable natural gas program offered by Vermont Gas Systems Inc., he noted.

Gas ban firewall grows across central, southern US

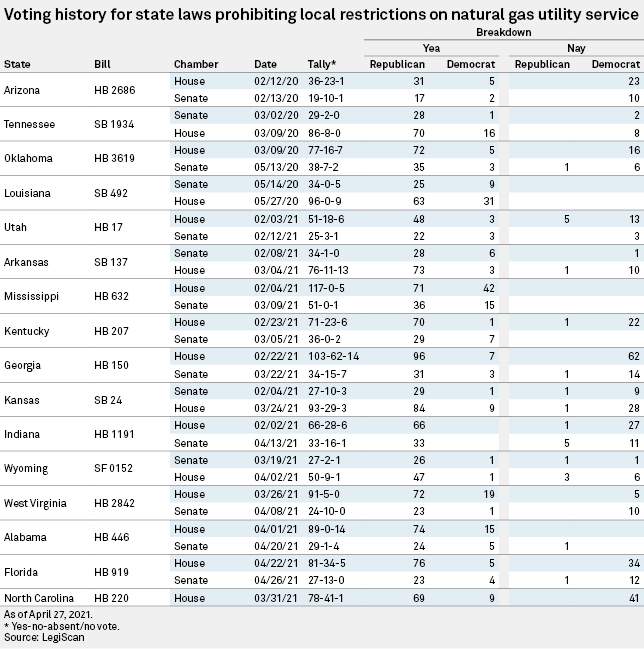

Since late March, governors in five states have signed into law bills that prohibit local governments from adopting building gas bans, bringing the 2021 tally of new state laws to eight and the total since 2020 to 12.

Kentucky's law prohibits counties and local governments from adopting any "law, ordinance, policy, resolution, code" or executive action that has the purpose or effect of prohibiting or restricting access to natural gas, manufactured gas or electric utility service, based on the energy source. The law also protects pipeline transportation of gas and crude oil for sale to utility customers. Lawmakers amended the original bill to prohibit restrictions on the sale of liquefied petroleum gas, or LPG, including propane, propylene, butane and butylene.

In Kansas, the newly adopted Energy Choice Act applies specifically to natural gas and propane, barring any "binding action" that prohibits or has the effect of prohibiting their use. It specifies that municipalities retain the right to pass measures that limit their own use of the fuels.

Iowa's law prohibits cities and counties from "intentionally or effectively" prohibiting the provision of natural gas service to any person, business or municipality. It additionally prohibits them from blocking the sale of natural gas or propane to those end-users. It also prohibits cities from restricting natural gas service in the course of "granting, extending, amending, or renewing" a utility's franchise.

A Wyoming law blocks cities and counties from enacting any ordinance, resolution or policy that prohibits or has the effect of prohibiting customers from connecting or reconnecting to electric, natural gas, propane or other energy utility service provided by a public, municipal or cooperative utility.

The West Virginia law states that counties and local governments do not have the power to pass codes, ordinances or land use restrictions that prohibit customers from purchasing, using, connecting or reconnecting to a utility service based on the type of fuel. It also says they cannot prohibit a public utility, private business or department of public utilities from furnishing utility service, or block them from using vehicles and equipment to provide utility services based on energy source.

Some bills stuck; several perched at the finish line

Four state legislatures have also passed bills in both chambers or laid legislation on their governor's desk. Meanwhile, legislation in Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Texas has yet to get a full chamber vote.

In Minnesota, whose legislature considered but did not pass similar legislation in 2020, Republicans introduced House File 2264, protecting access to natural gas and propane, in March. Minnesota is the only state to take up the legislation this year where control of the House and Senate is split between Democrats and Republicans.

The Alabama legislature sent House Bill 446 to Gov. Kay Ivey that would prohibit not only local governments, but also the state from adopting an ordinance, resolution, regulation or policy that prohibits or effectively restricts access to utility service from a provider authorized to do business in the state. It protects propane use and specifies that governments cannot deny a building permit based solely on the type of utility service planned for the project. Lawmakers struck a provision from an earlier version of the bill that said the law does not apply to municipal utilities.

Meanwhile, Florida lawmakers expanded the scope of House Bill 919, initially focused on prohibiting local restrictions on access to utility service for tenants and property owners. The final version blocks local governments from prohibiting or restricting fuel sources "used, delivered, converted or supplied" by electric and gas utilities; gas transmission companies; power generators; and LPG dealers, dispensers and cylinder exchange operators. An amendment specified that the law does not apply to municipally owned utilities.

Food & Water Watch warned that because the bill is so broadly worded and expansive — and because it applies to measures passed prior to the law's effective date — it could be used to overturn a wide range of local ordinances that promote clean energy and 100% renewable power. That could have a chilling effect on local climate action and lead to legal fights over existing ordinances, according to Brooke Errett, a senior organizer for Food & Water Watch in Florida.

"It seems the intent of the legislation is to wipe out these moves toward clean energy," she said. "Beyond it just wiping out these resolutions, [the concern] is what steps are cities going to be able to take without being exposed to the potential litigation from utilities?"

Indiana lawmakers also expanded early legislation beyond simply clarifying that cities, towns and counties lack the power to prohibit access to utility service based on fuel type.

The final version also says local units cannot require builders to use certain energy-saving components, designs or material types in construction, or mandate building retrofits that favor specific energy-saving or -producing devices or materials. It additionally prohibits local measures that restrict use of gas-powered home heating equipment, appliances and decorations; outdoor grills and stoves; and fossil fuel-powered vehicles or machines.