Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

29 Jan, 2021

Both sides of the building gas ban debate have kicked off the new year with a flurry of grassroots and legislative activity. Heading into 2021, the movement to restrict gas use in new construction in Washington and Massachusetts towns and cities continued to evolve, while state lawmakers sought to prohibit local governments from pursuing the policy.

Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan proposed an amendment to the city's energy code update that would prohibit fossil fuel combustion for space and water heating in new commercial buildings and multi-family residences. The effort marked the third attempt in Seattle to restrict gas use in new buildings since 2019.

One week earlier, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee put forward sweeping legislation that would phase out natural gas use in buildings through 2050.

In Massachusetts, more than a dozen towns and cities have launched a statewide campaign seeking authority to restrict gas use in new buildings, after the attorney general's office struck down the state's first gas ban.

The Massachusetts legislature on Jan. 4 passed a climate roadmap that included a potential mechanism for granting that authority. Gov. Charles Baker vetoed the bill, but said he was willing to work with the chamber on climate legislation in the next session. The Baker administration's own climate roadmap stressed transitioning to electric space heating.

States move to preempt local building electrification mandates

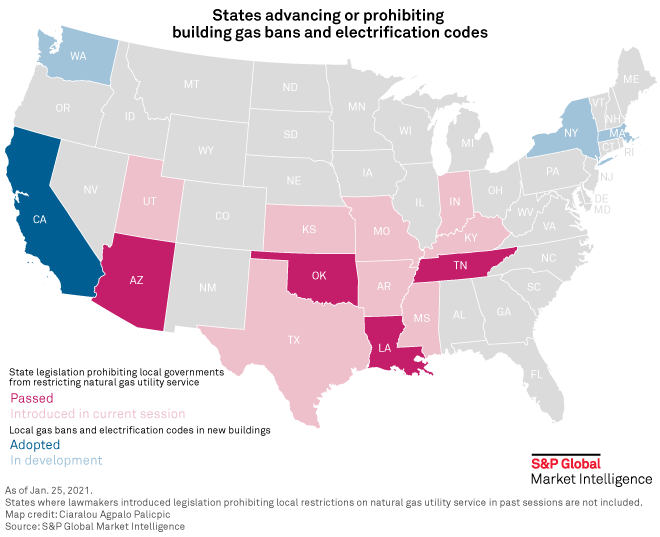

Lawmakers in at least nine states have introduced bills that would prohibit local governments from adopting California-style restrictions on gas use in new buildings. The legislative push continues a trend from 2020, when nine states introduced similar legislation and four states passed the prohibitions into law.

Like last year, the states where the legislation has been introduced are mostly in the South and Midwest: Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Texas and Utah. A Florida state senator filed similar legislation on Jan. 27. Three of those — Kentucky, Mississippi and Missouri — took up the legislation last year, but did not put it on the governor's desk. Lawmakers in Georgia and Minnesota have not yet introduced the bills, as they did in the last session.

Republicans control the state legislatures in all nine states and occupy the governor's mansion in each state except Kansas and Kentucky. Support for the bills has typically fallen along party lines, with Democrats often arguing against preempting local governments. However, the law passed in Tennessee generated bipartisan support and Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards signed Louisiana's prohibition into law.

Companies that have backed the bills include CenterPoint Energy, Inc., Duke Energy Corp., One Gas Inc. and Southern Co.

Karen Harbert, president and CEO of the American Gas Association, said the bill sponsors are representing the views of their constituents rather than the sentiments of a smaller group of gas opponents. In her view, most Americans do not want to be told what type of energy to use in their home. "That's a real American thing, right? I want choice," she said in an interview.

The Sierra Club, which supports building electrification, said the laws would hamstring local governments as they seek to mitigate climate change. "Cities need to have all options available when addressing climate impacts in their communities while continuing to be responsive to the will of their residents," the group said in a blog post.

California movement expands by several electrification codes, shrinks by one

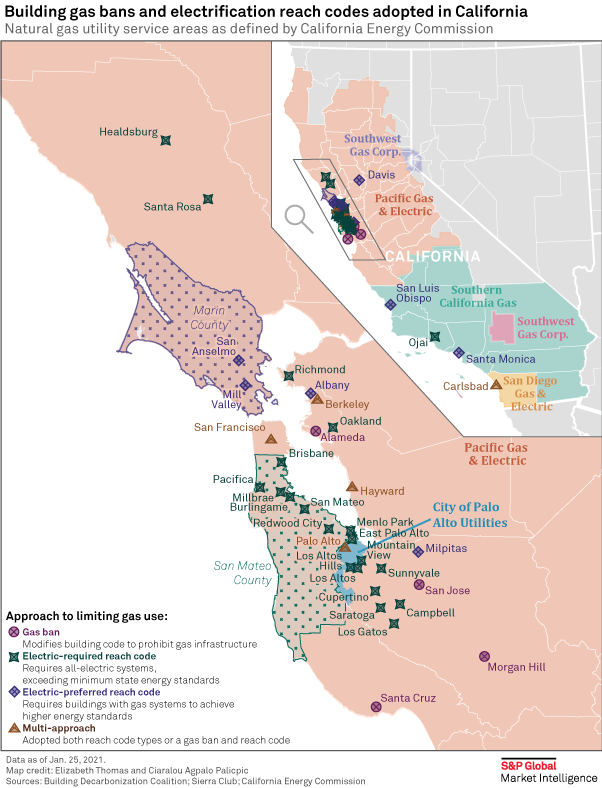

The Oakland City Council on Dec. 15, 2020, passed an ordinance requiring all-electric construction in new buildings, making Oakland the eighth-most populous Golden State city to restrict building gas use. The ordinance was remarkable for its lack of exemptions. It included a standard exception for cases in which all-electric construction is infeasible, but none of the typical carve-outs for commercial restaurants and industrial or research facilities.

The same day, San Jose, California's third-most populous city, expanded its existing building gas ban for small residences to most new construction.

Sunnyvale, Calif., on Dec. 1, 2020, adopted an ordinance requiring all-electric construction in both residential and non-residential buildings, the first part of the city's four-phase plan for decarbonizing buildings. The city allowed relatively few and very narrow exemptions.

It will permit natural gas for use in commercial kitchens, but applicants must show there is no electric alternative and install EnergySTAR-rated gas appliances. It also includes an exception for laboratories, factories and hazardous materials sites, as well as laundry facilities in large hotels. In later phases, the city would close the kitchen and hotel loopholes and require electrification in additions and alterations to existing buildings.

During debate in October 2020, the council added a new exemption for fuel cells, which convert natural gas into electric power on-site. The last-minute change previewed the San Jose city council's decision to adopt a similar exemption weeks later at the urging of Bloom Energy Corp., a fuel cell-maker based in that city and previously headquartered in Sunnyvale. In both cities, council members raised concerns about the reliability of the California electric grid following widespread blackouts.

The city council in Albany, Calif., on Jan. 19 adopted an ordinance that will require new homes, office buildings and commercial spaces built with natural gas infrastructure to achieve higher energy efficiency performance than all-electric buildings.

Elsewhere in California, the Windsor Town Council voted on Jan. 6 to rescind its all-electric construction mandate as part of a settlement with developers who sued over the ordinance, the North Bay Business Journal reported. Windsor was one of three communities in Sonoma County north of San Francisco that adopted the ordinances. Town officials said they intended to pursue an alternative ordinance, according to the Journal.

In Southern California, the Santa Barbara City Council on Jan. 12 asked city staff to report back with a proposed building electrification code for new construction. It asked staff to also look into electrification incentives for existing buildings and a workforce transition plan for impacted laborers.