Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

27 Sep, 2021

The future of wood biomass fuel for electricity generation in the United States balances on a knife-edge awaiting federal and state policy to determine if it more broadly qualifies as clean energy, experts and executives said.

Biomass fuel production, however, continues to grow in the Southeast to meet demand from abroad, with companies investing in plant expansions or additional facilities, even as some executives in the sector differ on its future.

Maryland-based Enviva Partners LP, which bills itself as the world's largest producer of wood biomass pellets, has a large production footprint in the Southeast, the world's "wood basket," and plans to continue expansion as export demand increases, with a hopeful outlook on future U.S. and global biomass policy.

"If governments and industry are genuine about tackling net-zero, we need to deploy negative emissions technologies urgently and at scale," Enviva Chairman, CEO and President John Keppler said in an interview. "The only way to get there is with sustainably sourced bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, which doesn't just offer opportunities to decarbonize the energy sector, but also heavy industries such as steel, lime and cement, making it an overarching tool to achieve our climate goals."

Environmentalists, climate scientists and biomass industry leaders are at odds over whether wood biomass qualifies as a carbon-neutral fuel. In the European Union, the question is more settled that it is carbon-neutral, and demand from abroad is driving the expansion of wood pellet production in the Southeast. But at home, those producers must navigate wildly differing policy treatments among states and at the federal level, threatening future growth.

Opportunities

Keppler said Enviva sees net-zero by 2050 goals by states and utilities as an opportunity for growth in new sectors "at a much faster rate than we could have ever imagined."

Whether that represents "a monetization opportunity" for companies like Enviva is a "real open question," Keppler said. To serve growing Asian and European markets, Enviva's strategy includes continued development of new production plans and marine terminals, with fully contracted plants in Lucedale, Miss.; Epes, Ala.; and a terminal in the Port of Pascagoula, Miss.

Drax Group CFO Andy Skelton said his company, which both produces wood biomass pellets and uses them to generate electricity at the 3,870-MW Drax Power Station in the United Kingdom, also sees broad and growing support for the fuel in Europe and Asia and considers its bioenergy with carbon capture and storage technology key to a net-zero future.

"We're exploring options to develop new [bioenergy with carbon capture and storage] plants — including in North America and we've recently partnered with Bechtel to explore such opportunities," Skelton said, adding that the company recently acquired Pinnacle Renewable Energy Inc. to increase production capacity and port access in Western Canada and the U.S. South. About two-thirds of Drax's biomass is sourced from trees in the Southeast U.S. The company also expanded capacity at two of its Louisiana plants, plans to add a new Demopolis, Ala., plant as part of the Pinnacle acquisition and add three new satellite plants in Arkansas, Skelton said. The majority of the new capacity will be commissioned in the fourth quarter of this year.

But while Keppler and Skelton forecast a robust long-term future, Active Energy Group PLC CEO Michael Rowan sees at least a partial expiration date for both "the big dogs," such as Enviva and Drax, and smaller companies like his.

"You've got to be realistic," Rowan said. "What we have in biomass is a transitionary technology. We know we want to get to the golden goal of renewable energy," and the CEO sees biomass playing a role in that transition. "We do produce less emissions, but we know ultimately that in 15 years' time there's going to be another human solution for energy. That is how we fit into the equation."

Rowan's company is working on another type of wood pellet called "CoalSwitch," designed for use in existing coal plants and "virtually agnostic as to feedstock source," aiming to reduce overall emissions. Part of the company's strategy is to meet the immediate transition needs of assets that might otherwise be stranded or converted to natural gas. Such an alternative could be attractive to countries with many coal plants still in operation, including the U.S., which is Rowan's focus, unlike many other biomass producers.

"You've got a huge coal business, and it won't go away very quickly unless you want all the lights to go out," Rowan said. "That's where CoalSwitch can fit and where we're getting some significant support."

Growing interest is coming from industrial businesses that use smaller amounts of coal and want to improve emissions, as well as PacifiCorp and some East Coast utilities, Rowan said, though he declined to provide further details.

In 2020, biomass overall, including wood and biofuels such as ethanol, equated to about 4.9% of U.S. primary energy consumption, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, and just under half of that was wood biomass. Transportation and industry accounted for the majority of consumption, with wood primarily used in combined heat and power plants for process heat and to generate electricity for their own use, according to the EIA.

Much of the wood harvested in the U.S. for use as biomass fuel, often processed into wood pellets, is shipped primarily to the European Union, and some argue that processing and shipping add to the total emissions of biomass.

At least part of the industry's future as a more significant electricity-generating fuel in the U.S. hinges on whether federal and state policy will classify wood biomass — technically renewable because trees can be replanted and eventually regrow — as a "clean energy" that qualifies for government incentives or will help utilities and private industry reach emission reduction goals, said Julio Friedmann, senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University, who formerly led the U.S. Energy Department's research and development program in advanced fossil energy systems.

But if other countries, particularly in Europe where demand is already high, proceed with subsidies and other incentives for this type of energy generation, and the cost remains competitive, the Southern U.S. could see its wood biomass production future solidify.

Political divide

Keppler said biomass cuts emissions and creates jobs, but scientists and advocates at the Southern Environmental Law Center and the Dogwood Alliance, among others, argue that wood biomass simply isn't as clean or as renewable as the industry purports. Some biomass producers faced pushback in the communities where they planned to or already set up shop, particularly vulnerable communities already facing economic and environmental hardship, and often communities of color in the South.

While some federal and state lawmakers, especially from heavily forested states, have for years urged the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Energy Department and other agencies to adopt policies favoring biomass and classify it as renewable, states including North Carolina, Virginia and Massachusetts have passed policy limiting wood biomass or excluding it from renewable portfolios.

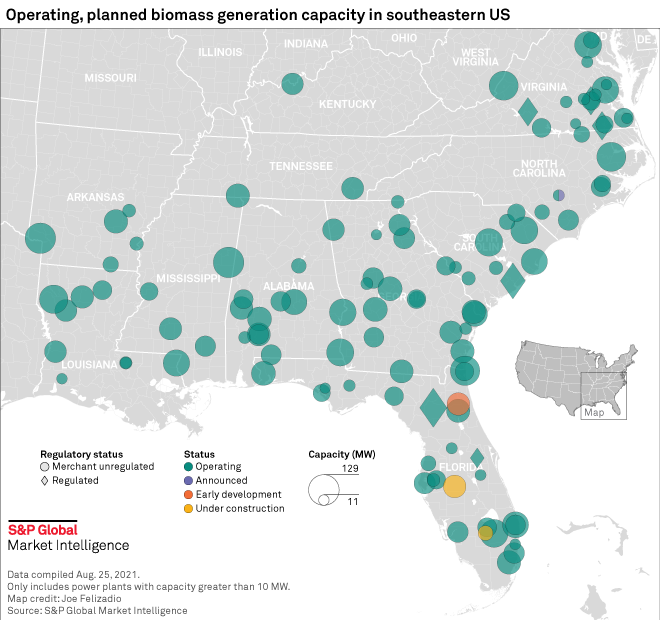

Georgia is second only to Florida in overall biomass electricity generation capacity, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data.

"Europe has shown us that treating biomass energy as clean energy makes sense and is effective at reducing greenhouse gases," Georgia Public Service Commission Vice Chairman Tim Echols said. "Creating biomass power generation in America doesn't happen by accident because it costs more. That means that the forestry industry, those who might use biomass energy and especially energy regulators must create carve-outs like we have here in Georgia in order to keep biomass energy viable."

Although the Trump administration was more supportive of wood biomass, Biden's EPA Administrator Michael Regan in 2019 told The [Raleigh, N.C.] News & Observer, when he led North Carolina's environmental agency, that he didn't "see a future in wood pellets," and "it doesn’t seem that this industry has the brightest future in selling itself as a carbon-neutral or sustainable industry." Shortly after taking office, Biden rescinded the EPA's draft ruling on the carbon neutrality of wood biomass.

'On a knife-edge'

The debate over the carbon neutrality of wood biomass has left the industry in a kind of limbo, with Rowan, like other industry leaders, keeping a close eye on U.S. policy developments.

"It's on a knife-edge," Rowan said. "We've heard it could go either way, and I can't see the way." Active Energy hopes the Biden administration will treat biomass as another bridge to a cleaner power system. "I'm not saying the industry should be extinct, but ... That's why you keep your plant sizes small and nimble," the CEO added.

U.S. wood biomass consumption for electricity has varied over the last 20 years, from a low of about 126.4 trillion Btu in 2001 to a high of 251 trillion Btu in 2014. In 2020, wood biomass reached a nine-year low at 185 Btu, according to EIA data.

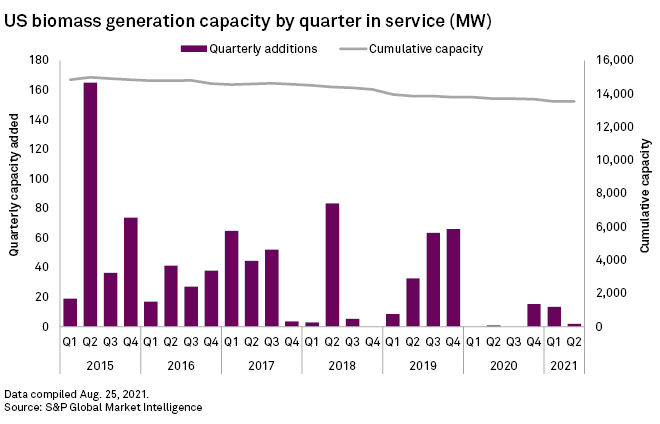

Relative to other fuels, few U.S. power plants use wood biomass, with the largest generating less than 130 MW, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. The largest operating biomass power plants in the U.S. by capacity are all located in the Southeast and more are planned, with the largest slated for Florida. But biomass generation capacity has also been declining since about 2015, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence quarterly in-service data.

With uncertainty surrounding the industry's future, some doubt whether it will become a significant source of U.S. electricity generation, even if the country continues to supply the rest of the world with wood pellets.

"Unfortunately, biomass generation will never be treated as mainstream and therefore never significant in the U.S.," said Echols. "That doesn't mean that we shouldn't make progress where we can."

"I do not see us going to wood pellet biomass power in the United States ever," Friedmann said. "It's just not competitive with clean options."