Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

28 Jan, 2021

|

China shipped 62% of the world's solar cells and modules in 2020, according to SPV Market Research. |

A surge of investment into America's solar industry last year meant big business for a group of manufacturers whose supply chains wind through China's autonomous Xinjiang region, an industrial hub where the U.S. State Department has said Beijing is committing "genocide and crimes against humanity" in its treatment of Uighurs and other Muslim minority groups.

Four of America's top solar panel suppliers during the fourth quarter of 2020 were companies that source the raw material polysilicon or other components from factories in Xinjiang, according to research firm Panjiva, corporate filings and Horizon Advisory, a consultancy that recently said it found signs of forced labor in China's solar industry.

The solar industry's exposure to Xinjiang creates regulatory

It is unclear how many of the solar panels shipped to the U.S. late last year contained material from Xinjiang. The Solar Energy Industries Association, a trade group, urged members in October 2020 to reroute their supply chains away from the region after U.S. Customs and Border Protection began seizing imports from Xinjiang and the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill that would ban goods that are made there unless the producers were proven not to have used forced labor.

While segments of the solar industry have moved quickly to avoid being implicated in potential labor abuses, though, analysts and market participants say some manufacturers in China have been slow to respond.

"There are some who have no news of this development or are completely dismissive of this threat," Andy Klump, CEO of Clean Energy Associates Ltd., a supply-chain manager, said in an email. "Those who have yet to make any changes to their solar supply chain will be caught off guard when the legislation passes, as the process to track and adjust their supply chain can take months."

'Genocide' in western China – U.S.

In a statement issued the day before President Joe Biden was sworn into office on Jan. 20, former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo accused the Chinese Communist Party of committing genocide and humanitarian crimes in Xinjiang, including the use of forced labor.

Antony Blinken, Pompeo's successor, said he agreed with the declaration. "I think we should be looking at making sure that we are not importing products that are made with forced labor from Xinjiang," Blinken said during his Jan. 19 confirmation hearing.

The Congressional-Executive Commission on China, a panel of U.S. lawmakers and administration officials that found forced labor in Xinjiang to be "widespread," said the House bill targeting imports from the region "will remain a priority ... in the 117th Congress."

With pressure building in Washington, solar manufacturers who fail to ensure that their supply chains are free from labor abuses could lose business in the U.S., said John Smirnow, general counsel and vice president of market strategy at the Solar Energy Industries Association.

China denies it is committing human rights abuses in Xinjiang. On Jan. 20, Beijing sanctioned Pompeo and other Trump administration officials. "[We] oppose interference in China's internal affairs under the pretext of Xinjiang and human rights, and we will firmly uphold national sovereign and security," China Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying said at a press briefing.

A spokesman for China's JinkoSolar Holding Co. Ltd., one of America's top solar panel suppliers, said the company does not use forced labor and "has already undertaken necessary steps to ensure that the U.S. supply chain uses long-term, contracted polysilicon, and ingot, wafer, cell, and assembly facilities from outside Xinjiang."

In December 2020, however, JinkoSolar said in a filing to the U.S. SEC that some products it sells into the U.S. could contain material from Xinjiang. The company said it "may" reconfigure its supply chains for U.S. customers if Washington enacts tight trade restrictions on the region.

"Any such maneuver could result in significantly higher manufacturing and other costs to us, delay our product supply to the U.S. market, and reduce demand for our products," JinkoSolar said in the filing.

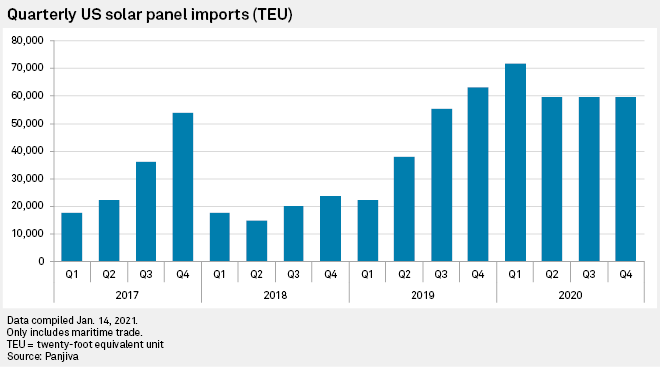

With U.S. panel imports up double digits in 2020, JinkoSolar, which operates a factory in Xinjiang, said sales to the U.S. accounted for approximately 31% of its revenues during the first nine months of the year compared to about 25% in all of 2019.

Several U.S. solar companies, including Sunrun Inc. and Sunnova Energy International Inc., told S&P Global Market Intelligence that they have asked vendors to certify that they do not use forced labor.

"We are committed to working with solar module manufacturers that align with our principles and ethical standards," AES Corp., which recently merged power plant developer Sustainable Power Group LLC into its U.S. clean energy business, said in a statement.

Most of the solar companies contacted by S&P Global Market Intelligence did not respond to messages seeking comment. The Trump administration tried using tariffs to pull some solar manufacturing back to the U.S., but so far the import taxes have had little effect.

Opaque supply chains

The U.S. still does not make nearly enough solar panels to meet domestic demand, and imports shot up 40% in 2020 as investment in the country's solar market rose 17%, according to data from Panjiva and research firm BloombergNEF.

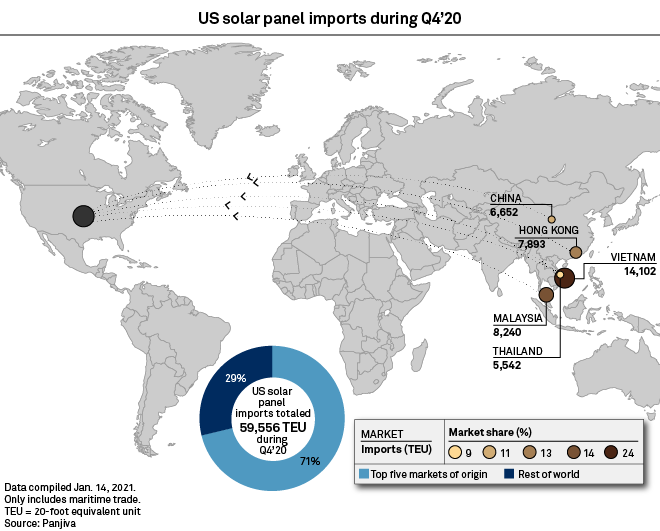

Of the roughly 59,500 shipping containers that delivered solar panels to U.S. ports during the fourth quarter of 2020, more than 70% were shipped from Asia, with nearly a quarter coming from China and Hong Kong.

Globally, China accounted for 62% of solar cell and panel shipments in 2020, according to Paula Mints, chief analyst at SPV Market Research. Including Chinese-owned capacity in other parts of Asia, the country's share of global shipments rises to more than 80%.

That dominance extends to polysilicon, a critical raw material in the manufacture of solar wafers and cells. About 80% of the solar industry's polysilicon capacity is located in China, with a majority based in Xinjiang, according to analysts.

After S&P Global Market Intelligence reported on the solar industry's heavy reliance on Xinjiang for polysilicon, a report from Horizon Advisory said that there are indications that China's top polysilicon companies and other solar manufacturers participate in resettlement programs for Uighurs in Xinjiang, "enlist" resettled laborers at production facilities in the region and implement "re-education" programs for resettled populations.

Products made by JinkoSolar, Trina Solar Co. Ltd. and LONGi Green Energy Technology Co. Ltd. contain polysilicon from Daqo New Energy Corp., according to Horizon Advisory, a supplier whose operations are "intertwined" with a paramilitary group called Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps that was sanctioned by the U.S. in July 2020 for "serious rights abuses." The firm also said a local government agency in Xinjiang reported last year that a JinkoSolar subsidiary qualified for subsidies for "absorbing" laborers and "recruiting Xinjiang nationals." GCL-Poly Energy Holdings Ltd., which supplies polysilicon to Canadian Solar Inc., has also received labor transfers in Xinjiang, Horizon Advisory said.

The firm did not receive outside funding for the report, said cofounder Nathan Picarsic.

A JinkoSolar spokesman said the Horizon Advisory report does not "demonstrate forced labor in our facilities." Daqo said in a statement that it has "a zero-tolerance policy towards forced labor in its own facilities and across its supply chain." Canadian Solar, LONGi and Trina, which were among the top suppliers of solar panels to the U.S. during the fourth quarter of 2020, did not respond to messages seeking comment.

Amid the increased scrutiny, some solar companies have reportedly begun sourcing polysilicon from factories outside of Xinjiang and are trying to use supply-chain tracing systems to verify they are not exposed to the region.

"While traceability in and of itself doesn't sound complicated, in this particular case it might be," said Paul Wormser, vice president of technology at Clean Energy Associates. "Module makers are really good, they have almost universally good traceability to everything that goes into the module assembly operation. ... It's when you go upstream, farther and farther back to polysilicon and perhaps even farther upstream, where the clarity of whether there is any sort of forced labor starts to get more difficult to obtain."

A higher standard

Further complicating matters, sourcing polysilicon from other parts of China may not insulate the U.S. solar industry from potential labor abuses. Uighurs have been forcibly transferred from Xinjiang to work elsewhere in the country, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, which is partially funded by the U.S. government.

"The labor transfer practices and forced labor extend well beyond Xinjiang, even if the genocide against the Uighur minority is particularly concentrated there," Emily de La Bruyère, a cofounder of Horizon Advisory, said in an interview. "They might say that they're going to move production, but the fundamental conditions aren't going to change."

For now, though, the solar industry's chief concern is the legislation in Washington targeting Xinjiang, said Wormser.

Elizabeth Levy, a portfolio manager and research analyst at Trillium Asset Management LLC, said she believes the solar industry will be able to root out potential labor abuses. However, companies could still pay a price with investors, customers and their own employees if they are not seen taking a public position on the issue, she said.

"They're in a tight position because the product that they're providing ... is seen as an unquestionable good. We're not going to be able to solve climate change without the involvement of solar panels. And so the expectation is that a solar company, at some level, is working to save the world," Levy said. "So either they get a pass and people don't look too closely at what they're doing ... or they're held to a higher standard. And I think that, in this case, they're going to be held to a higher standard."