S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

3 Jan, 2023

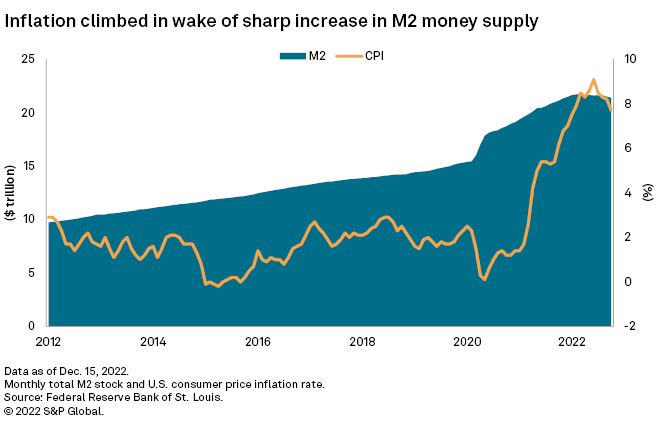

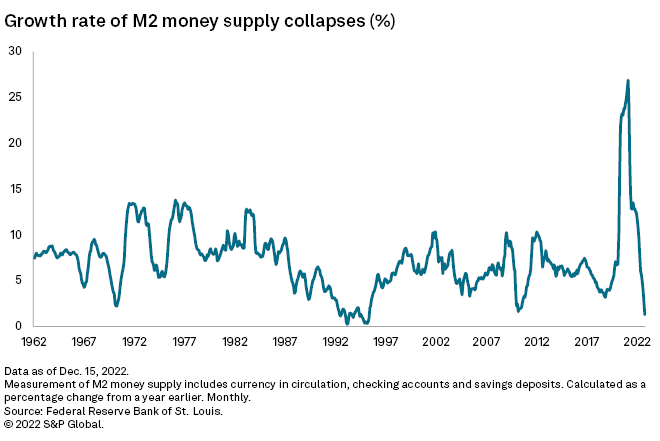

The Federal Reserve's aggressive push to tighten financial conditions has pulled some of the record-shattering money supply out of the U.S. economy, a sign that persistently high inflation is in decline.

The supply of M2 — cash, personal savings and market accounts that consumers can access — fell to $21.352 trillion in November 2022 from a peak of $21.740 trillion in March 2022, as the Federal Reserve's higher interest rates have taken effect. Inflation, meanwhile, slowed to 7.1% year over year in November 2022 from its June 2022 peak of 9%, the highest level in 40 years.

The drop in money supply is contributing to the slowdown in inflation as there is less cash in the economy to be spent on goods and services, reducing the supply-demand imbalance that helped push prices higher. The reduction is just one of the tighter monetary conditions currently putting some downward pressure on inflation, though a strong labor market and rising prices for services are pushing back.

"The recent decline in M2 is certainly helping the decline in inflation, along with other big things that are pushing down inflation, such as falling energy costs and shelter costs that are finally beginning to cool," said Luke Templeman, a research analyst at Deutsche Bank. "These are a function of other structural economic factors that will continue to pull down inflation next year."

Supply growth pushes prices

M2 was bolstered during the pandemic by the Federal Reserve's quantitative easing and government stimulus efforts. While that provided desperately needed liquidity for businesses, it seeped into the broader economy, including roughly $931 billion in direct payments to individuals through the end of 2021.

The total stock of M2 increased from $19.373 trillion at the start of 2021 to a peak of $21.740 trillion in March 2022. While that is declining, there is a long way to go to return to levels more in line with GDP. The total stock of M2 jumped from 70% of GDP to 90% and is now back to 84%.

At a time when global supply chains were in tatters, the stimulatory effects to demand contributed to the rise in inflation.

"Central bank asset purchases were far too large. They led to excessively high rates of money growth and, after a lag, to the inflation of late 2021 and 2022," Professor Tim Congdon of the University of Buckingham, a monetarist and former adviser on economic policy to the U.K. government, wrote in a Nov. 29, 2022, note.

The extent to which money supply determines inflation is hotly disputed by economists. Monetarists argue that the burst in inflation was an inevitable consequence of the Federal Reserve printing money, guided by the doctrine of Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman, who argued for low and stable money growth in the late 1950s.

"The current cyclical episode — like many before it — argues both that large fluctuations in money growth cause large fluctuations in the growth of demand and output, and that rapid growth of money results in inflation," Congdon said.

However, quantitative easing has been a recurring feature of central bank policy since the financial crisis in 2007-2008, a period marked by low inflation before the arrival of COVID-19.

"The massive increase in liquidity surely was stimulative but that doesn't have to transition into inflation," said Ken Matheny, executive director U.S. economics at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The supply of money, however, has little bearing on monetary policy decisions, Matheny said. Fed policy instead focused on reducing demand by disincentivizing spending through higher borrowing costs and the wealth effects of weaker stock prices and lower house prices.

Deposits decline as household finances creak

A more encouraging sign for the Fed is that while bank lending is still increasing, it is showing signs of slowing, while deposits are shrinking.

At the end of November 2022, loans and leases in bank credit for all U.S. commercial banks were up 11.8% from a year earlier, while deposits were down 1.3%, according to the Federal Reserve.

"Banks in aggregate are not deposit-constrained, so they are raising deposit rates more slowly than the Fed," said Lyn Alden, an independent investment research provider. "As a result, money has shifted over to [the Fed overnight reverse repurchase facility] instead."

Through the reverse repo program, the Fed sells securities to banks, allowing them to meet collateral requirements, and then buys them back the next day.

At the same time, the personal saving rate, the ratio of personal savings to disposable personal income, fell to 2.3% in October 2022, the lowest level since July 2005. The rate surged to a record 33.8% in April 2020 when government-mandated lockdowns caused spending to plummet.

Falling savings rates suggest households are using more of their income to meet their spending requirements, likely reducing demand for discretionary goods and services.

Other factors driving rising prices

Still, there are other signs that inflation may be stickier than originally believed.

The drop in M2 supply should indicate disinflation — a temporary slowing of inflation — or even falling prices, also known as deflation, said Michael Crook, chief investment officer at Mill Creek Capital Advisors. The rise, however, in the rate at which money is exchanged in the economy, also known as velocity, is creeping back up and offsetting that effect.

"Velocity is simply too unstable to make accurate forecasts based on changes in M2," Crook said.

While inflation roughly tracks M2, the movement in the money supply is not a "mirror image" of inflation, and Crook suggested inflation may take longer to fall as some components, such as services inflation, appear reluctant to move amid a strong labor market.

Broken international supply chains forced up the price of goods during the pandemic, driving inflation. The cost of goods is now falling, and it is now higher labor costs, feeding into rents and the cost of services, that are driving price rises.

Economists at Market Intelligence expect the increase in rents and services costs to reverse, but higher wages may prove to be longer lasting.

"What we've seen is wages have picked up, labor prices have picked up and inflation has. I wouldn’t call it a wage-price spiral, we haven't completed the loop, but we're getting close," Matheny said.