Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

11 Jan, 2022

By Zoe Sagalow

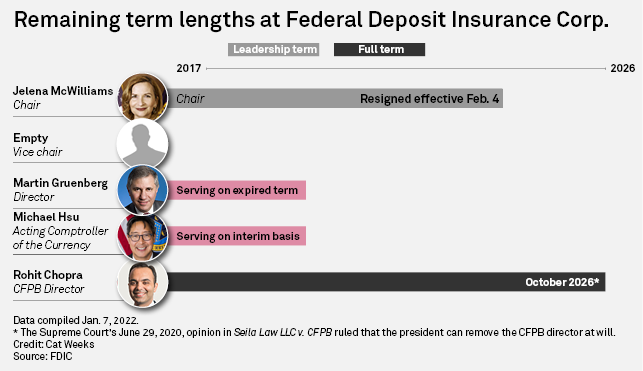

Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Chair Jelena McWilliams' resignation clears the way for the Democratic board members to pursue stronger rules in bank M&A and potentially in other policy areas, such as climate.

Martin Gruenberg, the former FDIC chairman under President Barack Obama and current board member, will take over as acting chairman when McWilliams steps down Feb. 4. Gruenberg and fellow Democrat Rohit Chopra, director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, co-authored a joint statement seeking public comment on whether agency merger rules should account for systemic risk and consumer abuse concerns. They published their request without McWilliams' prior approval.

After McWilliams' departure, Gruenberg will control the FDIC Board's agenda and will probably follow up on his and Chopra's proposal, said Chip MacDonald, financial services lawyer at Jones Day who works on mergers and acquisitions, in an email. That would add to financial institutions' M&A woes, which include a backlog of large deal approvals.

"The climate [for bank M&A] was bad before McWilliams resigned," Isaac Boltansky, director of policy research at BTIG LLC, said in an interview. "The climate will remain bad."

The overwhelming Democratic majority on the board is expected to put pressure on financials in the near term, wrote Edward Mills, managing director and Washington policy analyst at Raymond James & Associates Inc., in a Jan. 3 note to clients. Specifically, banks that merge to form an entity with over $100 billion in assets may draw heavy regulatory scrutiny, as Gruenberg and Chopra cited that figure in their joint statement, which warned of the perils of ongoing consolidation in the industry.

A case-by-case approach would be better than a $100 billion threshold, said Joseph LaVorgna, chief economist for the Americas at Natixis. A merger might result in a bank with $99 billion in assets, just under the threshold, and receive less scrutiny. But a weak bank might merge with a strong bank and exceed $100 billion in assets and be denied even though it is a positive merger. LaVorgna also questioned whether the threshold would be adjusted for inflation.

The McWilliams resignation was just the latest chapter in a series of events that have portended more difficulty for banks seeking to merge. Financial institutions had already been looking for a break in a backlog of large deal approvals that lawyers and analysts attributed to factors like a July executive order by U.S. President Joe Biden calling for updated merger guidelines for banks and tougher scrutiny of deals.

Although Democrats have criticized regulators for approving too many mergers of late, the reason so many are approved is that companies check with regulators in advance, said Thomas Vartanian, a former general counsel of the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corp. and the Federal Home Loan Bank Board in the Reagan administration. If the companies realize a merger will not be approved, they do not propose it, Vartanian added.

Agency independence

The battle at the FDIC drew the attention of Republicans and Democrats in Congress, with Senate Banking Committee Ranking Member Pat Toomey, R-Pa., criticizing Gruenberg and Chopra's "reckless effort" to take over the board. Chairman Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, encouraged the board to proceed with its supervisory work, and House Financial Service Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters, D-Calif., requested the FDIC, Federal Reserve and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency impose a moratorium on approving M&A applications that would result in a banking entity having over $100 billion in total assets.

The actions of the Democratic FDIC board members and the response by legislators signal a more politicized agency, Vartanian said.

"The banking agencies have always been pillars of stability because their job is to encourage financial stability throughout the country," he said. "The more you politicize these agencies the more you're playing with fire by creating circumstances and events that will make financial markets and the economy less stable."

Climate

In addition to tougher M&A rules, the Biden administration has made addressing climate change risks a priority. With McWilliams gone, the FDIC may redouble its efforts on that front as it has lagged other agencies, said Jeremy Kress, assistant professor of business law at the University of Michigan.

The FDIC may provide guidance that would inform banks of climate risks they face and how to address them, and it may incorporate climate metrics into Community Reinvestment Act examinations, said Todd Phillips, director of financial regulation and corporate governance at the Center for American Progress, which focuses on progressive policies.

"In the longer term, I think we could see the FDIC begin doing climate scenario analyses of how banks will fare in different climate scenarios," Phillips said in an interview.

For bankers, this may not require much change in their operations.

"Although there are always new developments, environmental concerns are nothing new for bankers," John Geiringer, a partner in the Financial Institutions Group at Barack Ferrazzano Kirschbaum & Nagelberg LLP, wrote in an email. "They must evaluate the full spectrum of risks, including environmental risks, that could prevent borrowers from repaying their loans."

Potential replacements

McWilliams' resignation on Dec. 31, 2021, likely happened too quickly for the White House to already have a list of names at this point, Vartanian said.

A White House spokesperson declined to comment on Biden's plans for appointing a permanent replacement.

There seems to be less urgency for the Biden administration to nominate someone once there is someone acting in a position, Raymond James' Mills said in an interview.

"Permanent acting directors are not unusual at this point," Mills added.