S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

25 Apr, 2022

| People walk by a branch of Rosbank, the Russian subsidiary that French bank |

European banks operating in Russia have to decide between two unappealing options — either make a hurried and probably costly exit that leaves international clients stranded, or stay put and deal with the complexities of international sanctions as well as the risk of a backlash at home.

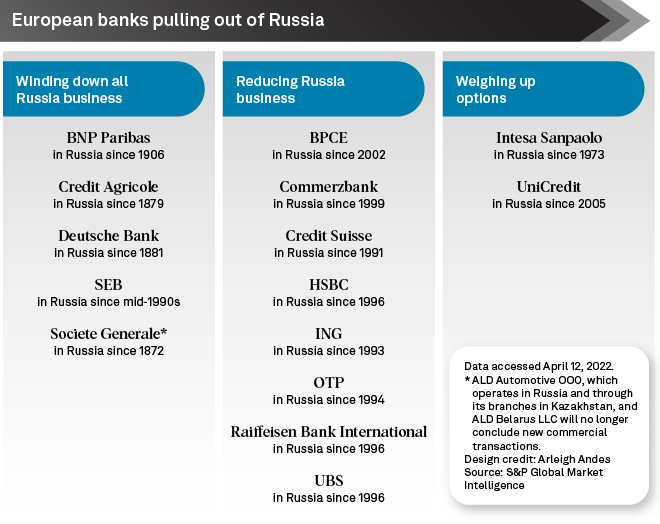

Société Générale leads five banks rapidly exiting Russia, with the French lender saying it will take a loss of about €3.1 billion on the planned sale of its local unit. By contrast, its two biggest overseas rivals in Russia, UniCredit and Raiffeisen Bank International AG, are remaining for now, even amid international protests, following President Vladimir Putin's invasion of Ukraine.

Leaving Russia is a potentially costly move because European banks have large exposures they would struggle to off-load amid global sanctions. According to the Bank for International Settlements, they have more than $84 billion of exposure to the country. They would also have to abandon profitable and still-legal activities, such as agricultural or commodity financing, as well as ditching contractual obligations and potentially abandoning global clients wanting help in winding down their own Russian operations.

"Exiting is not a smooth process," Gwen Green, an international compliance attorney at Holland & Hart, said in an interview. "There's a lot to untangle."

Banks must assess the full scope of their exposure, calculate the potential financial losses they would have to absorb and decide what to do with their local staff, Green said.

But remaining in Russia poses reputational risks and lower potential rewards as the impact of sanctions on Russia's economy erodes the historically high returns banks are used to, Sam Theodore, senior consultant at credit research company Scope Insights, said in an interview. Banks can absorb the loss of their Russia businesses thanks to strong capitalization and high loan loss provision buffers rolled over from the COVID-19 pandemic, Theodore said.

European banks should sever all ties with Russia and leave sooner rather than later as they will not be able to ensure that part of their Russia-based corporate lending, local tax payments or public debt holdings does not end up supporting the Ukraine war, Theodore wrote in a March 24 report.

Cost of exiting

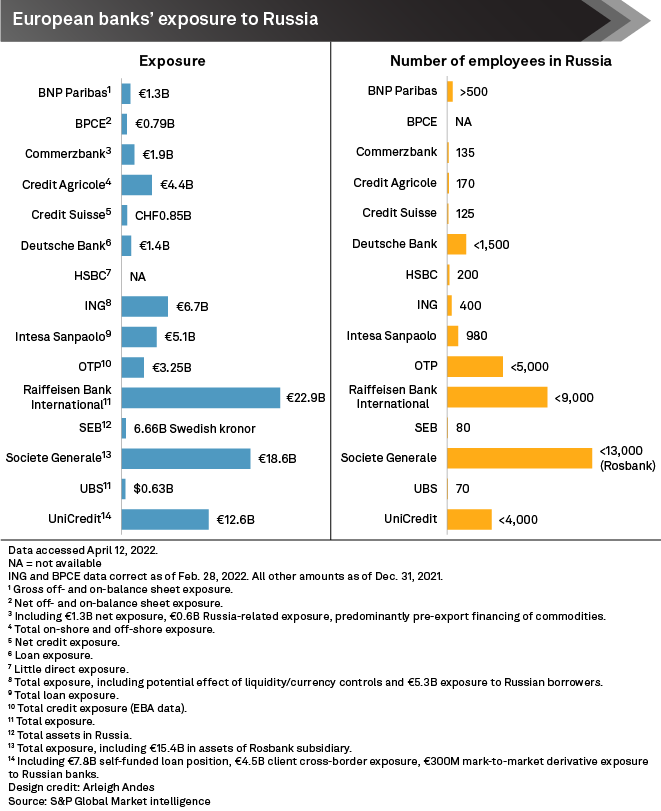

European banks face the highest potential cost of exiting Russia as they account for most of the $121 billion of total foreign banks' exposure to the country, BIS figures show. RBI, UniCredit and Hungary-based OTP Bank Nyrt. each have thousands of employees in the country.

RBI has the highest exposure of €22.9 billion, according to data compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence. The Austrian bank said it would explore options, including an exit, after initially saying it would stay. Raiffeisen Bank Russia "will continue to substantially reduce its lending and will not actively seek to acquire new client relations," a spokesperson told Market Intelligence.

Italy-based UniCredit is also biding its time. The bank has exposure of €12.6 billion, most of which is a self-funded loan position. Unwinding a bank with 4,000 employees and more than 1,500 corporate clients, and absorbing a loss of up to €7.5 billion, "cannot and should not be done overnight," UniCredit CEO Andrea Orcel said in a March 15 statement.

UniCredit continues to monitor and "thoroughly assess" the evolving geopolitical situation, a spokesperson told Market Intelligence. OTP is winding down its Russia-based corporate lending and has stopped investing in and trading of Russian government securities, a spokesperson said.

SocGen is the only European bank with a large overall exposure and Russian retail banking operations that has decided to exit, having agreed to sell Rosbank to the latter's previous owner, Russia-based Interros Capital. It is also selling its insurance operations and said its ALD leasing business will not conduct new commercial business. If the deal goes through, SocGen will likely take a write-off of €2 billion along with a noncash charge of €1.1 billion.

Most that have sought to pull out so far either have little direct exposure or few local staff, or no retail banking business with local deposits. Germany's Deutsche Bank AG and French bank BNP Paribas SA both have been reducing their Russian operations for the past few years. Crédit Agricole SA's more sizeable exposure is tied to corporate clients only. Sweden's Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB (publ) is also exiting.

For those that remain, mounting reputational pressure is leading to a reassessment of Russian operations, Barbara Laidlaw, head of global reputation risk and public affairs at U.S.-based PR agency Allison+Partners said in an interview.

The market expects them to move quickly. Given the public outrage around Russia's aggression in Ukraine, shareholders are likely urging banks to set out a Russia strategy, and they cannot be seen to be "dragging their feet," Jeremy Cohen, partner at London-based business management consultancy Blurred told Market Intelligence.

Most of the leading European banks, even with limited exposure, rushed to issue statements on their Russia business in March and April.

'Last boots on the ground'

Still, a swift exit could be tough. Banks are expected to help clients unwind their own positions in Russia, Laidlaw said. More than 600 companies have announced their complete or partial withdrawal from Russia since the invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, according to research by the Yale School of Management. Many European banks have confirmed they are assisting clients unwind Russia-linked transactions.

Banks also have their own contractual agreements with clients they cannot simply walk away from, according to Daniel Tannebaum, global head of sanctions at consulting firm Oliver Wyman.

Global banks also support ongoing foreign trade in sectors unaffected by the current sanctions. Some Western banks are heavily involved in financing agricultural products and other commodity transactions, which are still legal, Tannebaum said in an interview.

"Until the commerce fully stops, the banks will be the last boots on the ground because someone will need to finance the activity," Tannebaum said.