Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Apr, 2021

By Yannic Rack

| Exhaust from a gas-fired power station in Berlin. Some utilities are building new gas plants even as they set phaseout dates for the fuel. Source: Sean Gallup/Getty Images News via Getty Images |

.

|

In a strategy presentation in February, Miguel Stilwell de Andrade, CEO of EDP - Energias de Portugal SA, pledged that his company, one of Europe's biggest utilities, would not own any natural gas-fired power plants in 2030, the date by which it wants to reduce its direct emissions to net-zero.

The commitment came less than a month after another power giant, Enel SpA, said it would get out of gas by 2050, its own target date for carbon neutrality. "That's clearly a future where there is no gas," said Salvatore Bernabei, CEO of the utility's renewables business.

The statements were some of the clearest indications yet that natural gas, long hailed as a transition fuel by policymakers and industry advocates in Europe and elsewhere, is starting to lose its luster for the largest energy producers as they strive to reach net-zero.

Yet even as they tout expiration dates for gas, many utilities are still building new power plants that burn the fuel, betting that early-stage or costly technologies such as hydrogen electrolysis and carbon capture and storage will give them a long-term future.

In Italy, Enel wants to convert several coal plants it owns to natural gas over the coming years. Meanwhile, Engie SA plans to build four gas plants in Belgium, where RWE AG has just acquired a 920-MW project. The latter has also won contracts to build gas-fired backup capacity in Germany.

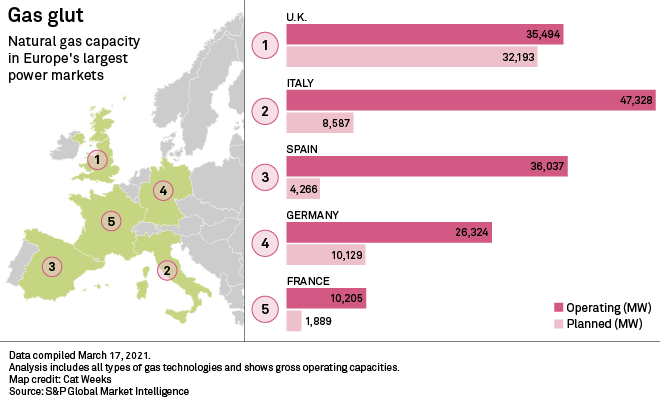

Across Europe's five largest power markets, developers have announced more than 60,000 MW of gas plant projects, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. That adds up to almost twice the entire power capacity of the Netherlands, even if challenging economics mean many of the projects are unlikely to be built.

Government policies are driving some of the projects that are advancing. Coal and nuclear phaseouts are set to squeeze power supplies in Germany and Belgium, for example, and many governments incentivize operators to bring gas plants online as standby capacity in case of shortages.

'Big challenges'

The situation increasingly resembles a tightrope walk for utilities charting a path to their climate targets.

Dominic Nash, head of European utilities research at Barclays, said companies will face an uphill battle trying to achieve net-zero while also making sure that they can balance out intermittent renewables and keep the grid stable.

"I don't think net-zero for utilities is crazy," Nash said. "I don't think there's any reason why they cannot do it. But there are going to be some big challenges to get there."

In the meantime, gas has become the new battleground for environmental policy in the EU.

The European Investment Bank, Europe's largest public lender, has already tightened its lending policy to largely exclude financing of new gas infrastructure from the end of this year. And the European Commission, the EU's executive, is under pressure to all but exclude natural gas from its upcoming green taxonomy, a rulebook for investors looking to put money into sustainable activities.

Even if the bloc bows to political and industry demands to leave the door open to natural gas, EU climate czar Frans Timmermans has made it clear that time for the fuel is limited.

"Fossil gas is a fuel that will need to be scaled back at considerable speed as we pursue the transition to net-zero," Timmermans, the EC's executive-vice president for the European Green Deal, told the gas industry at a recent event.

| An LNG terminal on the Isle of Grain, in the U.K. Companies' climate targets often do not account for the emissions generated by trading and selling gas to customers. |

'A lot of risk'

Utilities emphasize that they are only building new gas plants that can be retrofitted to zero-emission operations later on. But some analysts warn that building new capacity is nonetheless becoming a daring proposition since it is unclear whether technologies like carbon capture will ever be viable on a large scale.

"There's a lot of risk in doing this," said Catharina Hillenbrand von der Neyen, head of power and utilities at the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a think tank. "You could get on that path to uneconomic [operations] pretty quickly ... as an investor, I'd be extremely nervous about a company who wants to do a new gas plant with a 30-year lifetime."

In Italy alone, developers risk as much as €11 billion in stranded gas investments since the capacity market for backup power "significantly distorts" their investment case, according to a Carbon Tracker analysis. New-build plants are no longer cost-competitive compared to cleaner alternatives like renewable energy and batteries, according to the think tank.

Some companies seem to be waking up to the fact that gas may not have much of a future.

Drax Group PLC recently abandoned plans to build two large natural gas units at Britain's largest power station after failing to secure capacity payments from the government. Only two months earlier, the company sold its last remaining gas plants in the country.

In Spain, where the government does not pay operators for standby capacity, analysts have warned that only a handful of the country's 51 combined-cycle gas plants would be economically viable by the end of the decade under the current regulatory framework.

Naturgy Energy Group SA, Spain's largest owner of gas-fired capacity, has requested government approval to temporarily shut down some of its units. Gas plants in the country have been running at much lower capacities than they were designed for, according to an analysis by consultancy PwC cited by Argus Media.

In February, Naturgy said it had written down the value of its gas-fired plants in the country by €1.15 billion in 2020 due to the drawn-out effects of the coronavirus pandemic on energy prices and the EU's increased target for emissions reductions by 2030.

The EU climate goal, in particular, "changes the perspectives that we have in the long term," said Jon Ganuza, the utility's global head of controlling.

'Smoke and mirrors'

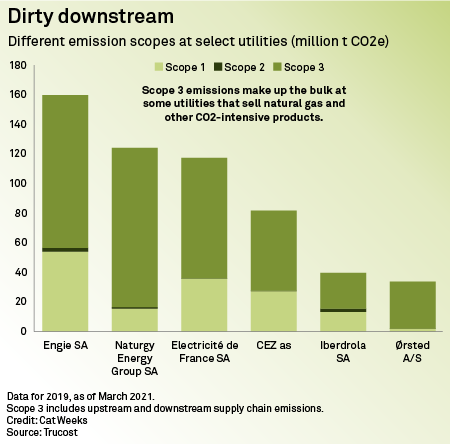

Gas is not only found in utilities' power plants, however. As more companies announce net-zero targets, focus is increasingly shifting to harder-to-abate emissions — including those created when customers burn fuels, known as Scope 3 emissions.

For some power companies that trade and sell natural gas, these far outweigh the direct emissions from their power plants, known as Scope 1, which utilities have mainly focused on when setting their climate targets. Only nine of the roughly two dozen largest utilities in Europe have set net-zero targets that include their Scope 3 emissions.

|

Naturgy's Scope 3 emissions in 2019 were almost seven times as large as its Scope 1 emissions, according to emissions data from Trucost. The company is a major trader of LNG and, with more than 5 million supply points, claims to capture almost 70% of Spain's natural gas market.

At other utilities, including Engie, Iberdrola SA and Electricité de France SA, Scope 3 emissions are roughly twice as high as Scope 1 emissions.

A spokesperson for Naturgy said the company's strategy to lower its emissions includes offering environmentally friendly alternatives to its customers, such as renewable gas and natural gas with emissions offsets. Naturgy only has targets to reduce its Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, which it says are under review. Scope 2 emissions mostly comprise those from purchased energy.

Ørsted A/S, perhaps the company most frequently held up as a poster child for the energy transition, reduced its direct emissions to 1.8 million tonnes in 2019 — far lower than any of its peers. Yet the company's emissions from the wholesale buying and selling of natural gas still accounted for more than 30 million tonnes of CO2 that year. It has since reduced Scope 3 emissions by around 9 million tonnes due to the sale of its LNG business and the temporary shutdown of a gas field in the North Sea.

A spokesperson said meeting the company's emissions-reduction targets, which include halving Scope 3 emissions by 2032 and eliminating them by 2040, will require gradually phasing out its natural gas business while engaging closely with its suppliers to reduce their emissions as well.

Other companies are stepping up their game, too. Fortum Oyj and EDP have both said they are developing more stringent Scope 3 reduction targets this year. But analysts say the focus on Scope 3 emissions in the industry is still too low.

"They're excluding this massive pool of their carbon footprint. There's all this smoke and mirrors in this market," said Kyle Harrison, senior associate for corporate sustainability at BloombergNEF.

However, Harrison said that as utilities move toward eliminating their direct emissions and shift their businesses accordingly, their remaining carbon footprint will likely shrink as well. And while net-zero target-setting still resembles the "Wild West," he believes an effort by the Science Based Targets initiative to come up with a standardized net-zero framework will help illuminate companies' blind spots.

"There's going to be a lot more scrutiny on how will they do it," Harrison said. "Utilities will have to start taking that a lot more seriously."

EDP's Stilwell de Andrade emphasized that the company's 2030 net-zero target means it still "has a few years" to figure out how to get out of gas, which could include simply selling its plants.

As carbon-neutrality targets become the norm, more companies will soon face the same choice.

"You won't achieve net-zero with a gas fleet," said Harrison. "It's cleaner than coal, but it's not going to get you there."

Trucost is part of S&P Global Market Intelligence.