S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

8 Mar, 2022

By Sanne Wass and Camilla Naschert

| A nuclear power plant in Nogent-sur-Seine near Paris. Access to capital for owner EDF will be widened by the inclusion of nuclear in the EU taxonomy. |

Europe's ethical investors may soften their attitude toward nuclear power after the carbon-free technology won EU recognition as a sustainable activity.

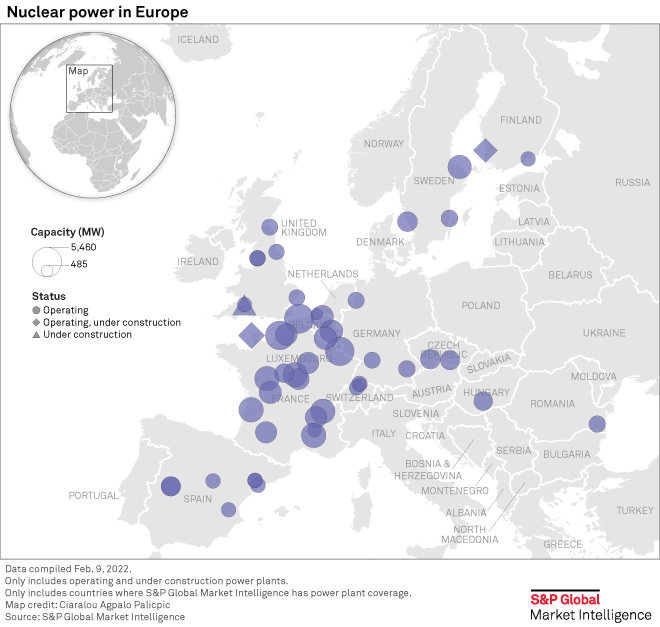

Nuclear will join the EU's green taxonomy next year, potentially easing investor concerns about whether it should be considered environmentally friendly. The move could in turn open new funding sources for European nuclear operators, such as Electricité de France SA, or EDF, and Fortum Oyj, as the industry faces up to €550 billion of investment needs through 2050, based on EU forecasts.

"The perception is shifting" among environmental, social and governance investors, said Marina Petroleka, global head of ESG research at Sustainable Fitch. "Suddenly nuclear is back in the conversation."

The new green status adds to growing momentum for the power source in Europe as technology developments and greater appreciation for nuclear's ability to consistently supply carbon-free power increasingly outweigh traditional worries about radioactive waste and safety levels. The conflict in Ukraine may further accelerate the trend by heightening concerns about Europe's reliance on Russian gas.

Paring this dependence will likely require "a comprehensive energy mix," said Guillaume Mascotto, head of ESG strategy at Jennison Associates, an investment company. That includes prolonging the life of nuclear plants, as well as using renewables and LNG, Mascotto said.

In a potential first sign of this trend, Fortum said March 3 it planned to extend the lifetime of two units of its Loviisa nuclear power plant in Finland to 2050.

Changing investor attitudes

The EU's taxonomy is "clearly setting the expectations and setting a guide," said Kenneth Lamont, a senior research analyst at Morningstar. It will help establish the parameters for nuclear investments and could boost public confidence in the technology in the longer term, Lamont said.

The green finance rulebook may help ease investor concerns about nuclear because it sets out strict safety and environmental criteria that must be met for a project to be labeled green, Goldman Sachs analysts said in a January note.

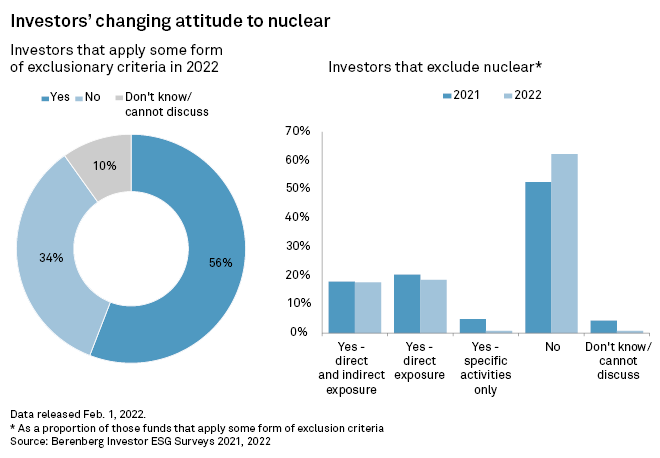

A shift in investor attitude is already underway, with only 37% of funds with exclusions now barring nuclear assets, according to a Berenberg ESG survey of more than 200 fund managers in Europe and North America. That is down from 43% in a similar survey a year earlier, the investment bank said in a Feb. 1 note.

Nuclear's inclusion in the green taxonomy could further boost acceptance, providing a spur to shares of EDF and Fortum, which are both involved in constructing new projects, Berenberg said. The investment bank also highlighted Enel SpA, Iberdrola SA and E.ON SE, which have direct or indirect exposure to existing plants scheduled for closure, as potential winners from the change.

Admission to the EU taxonomy could let European nuclear developers sell green bonds to help fund new plants, which was previously unheard of in the region, said Petroleka.

That would potentially cut borrowing costs for huge spending programs due to investor demand for ESG assets. Canadian generator Bruce Power Inc., which sold what it said was the world's first green bond for nuclear power in November 2021, estimated that the bond carried a 3-basis-point "greenium," reflecting the funding cost advantage associated with a green label. The C$500 million issue was 5.6x oversubscribed.

The Bruce Power bond has spurred interest in green finance for nuclear and the taxonomy will likely encourage investors further, said Christa Clapp, managing partner of Cicero Shades of Green. The Norwegian green-bond rating provider endorsed the Bruce Power security.

Easing capital access

A more open-minded investor attitude in light of the taxonomy inclusion will help European nuclear companies including EDF, said Antonio Totaro, deputy head of Europe, the Middle East and Africa utilities and transport at Fitch Ratings.

EDF is funding U.K. plant Hinkley Point C and French reactor Flamanville 3 through its own balance sheet for a total of about €40 billion, Totaro said. But for new plants, including the proposed Sizewell C plant in the U.K., it envisages going to the market for a large part of the funding, which may be supported by the taxonomy, he said.

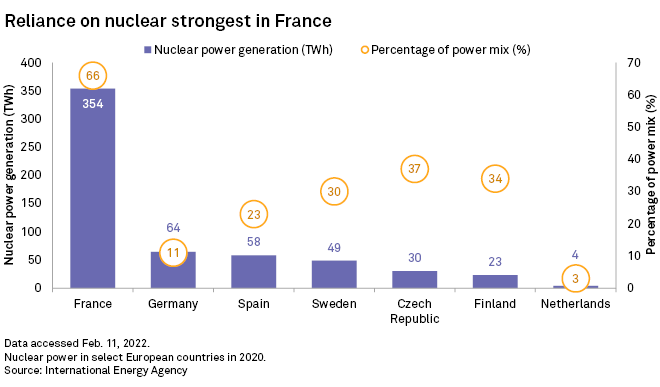

The French government, the majority shareholder of EDF, could also issue sovereign green bonds for nuclear power, according to Thomas Gillet, associate director for sovereign and public sector ratings at Scope Ratings. The addition of nuclear to the EU taxonomy is credit positive for France, Europe's biggest user of nuclear power, Gillet said in a January note.

Companies developing new technology for nuclear will likely also be placed to attract more ESG-labeled investments in the future. The development of smaller, flexible reactors that generate considerably less waste would be an "interesting perspective" for investors such as Pension Denmark, said Jan Kæraa Rasmussen, its head of ESG. The Danish pension fund, which manages €40 billion in assets, may start to invest in nuclear once the new technology becomes scalable, he said.

The French treasury department declined to say whether it would consider offering green bonds to support nuclear generation. Its current green-finance framework does not cover the technology. EDF declined to comment on the taxonomy.

Fortum said it welcomes nuclear's addition to the taxonomy as a "crucial step toward European energy transition." Nuclear can help mitigate climate change because it provides baseload low-carbon power not subject to volatility like wind and solar.

Risks remain

Still, not all investors will start to accept nuclear just because it is on an EU list. The bloc's own lending arm, the European Investment Bank, for instance, has already said that it has no intention of financing nuclear.

Many green funds will likely stay away too, said Isobel Edwards, investment analyst for green bonds at NN Investment Partners. "We already have policies, which we don't change based off the EU announcements," she said.

Investors are in particular concerned with reputational risk and possible accusations of "greenwashing" from environmental campaigners.

Opposition to nuclear remains strong in countries such as Germany, Austria and Luxembourg, which all opposed adding nuclear to the taxonomy. Germany is shutting its last reactors at the end of this year. Some energy experts and environmental groups are also against the change.

This may put investments at risk as opponents will likely seek to challenge and sue new projects, said Alain Vallée, president at French consultancy NucAdvisor, who spent three decades at French nuclear giant Framatome. "Having nuclear included inside the taxonomy will not stop the fight of several countries against nuclear energy," Vallée said.

For now, the opposition is unlikely to have the required numbers to prevent member states and the European Parliament from signing off on nuclear's addition to the taxonomy, according to Berenberg.

Financial concerns may also deter investors from putting money into nuclear. Plants have vast up-front costs, and there is a long wait for profits due to lengthy development and construction times, particularly in comparison to renewables. Recent new-builds, including the Finland's Olkiluoto nuclear plant, France's Flamanville 3 and the U.K.'s Hinkley Point C, all suffered from huge delays and cost overruns.

Such issues further complicate both efforts to raise investment for nuclear and policy makers' reliance on the technology to meet environmental goals. The European sector will need to draw €500 billion of investments into new-generation power stations by 2050 and a further €50 billion into existing plants to achieve the EU's net-zero objective, European Commissioner Thierry Breton said in January.

Still, nuclear's entrance into the EU taxonomy should provide some help by at least opening the door to funding from the ESG sector.

The change will allow "more nuanced views" of nuclear, analysts at Goldman Sachs said in the January note. It could mark the "beginning of a shift away from traditional hardline investment exclusions."