Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

9 Aug, 2021

By Brian Scheid

|

|

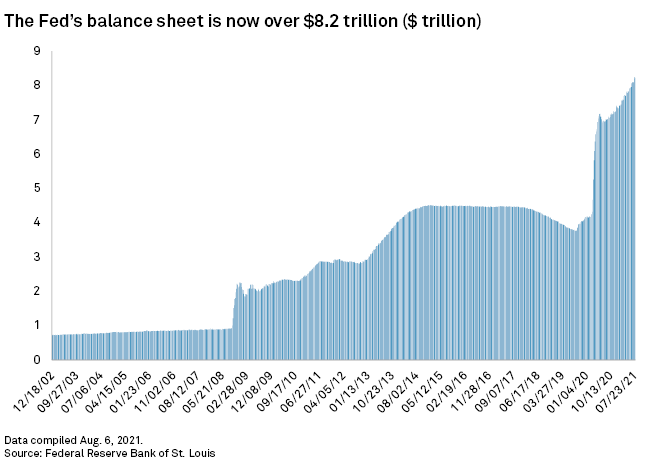

After more than doubling its asset holdings over the last two years to more than $8 trillion, the Federal Reserve is facing growing criticism over its swelling balance sheet as a substantial market disruptor.

The central bank's holdings and continued $120 billion per month in securities purchases are upsetting markets — sending stock valuations to new highs and pushing corporate and government bond yields artificially low — and the Fed needs to look at trimming its stockpile, economists say.

"By holding these large bond portfolios [the Fed] is pushing down yields, pushing up asset prices by implication, pushing down spreads and reducing credit discipline," Paul Gruenwald, global chief economist with S&P Global Ratings, said in an interview. "That was great for fighting the global financial crisis and the COVID crisis, but is that what the Fed should be doing over the longer term?"

The Fed's balance sheet steadily declined throughout much of 2019. Since then, pandemic-era monetary policy has added more than $4 trillion to its holdings, which hit roughly $8.235 trillion as of Aug. 4, equivalent to about 36% of U.S. GDP.

Before the pandemic, trimming the Fed's holdings was a priority for Chairman Jerome Powell after the central bank's balance sheet ballooned under a quantitative easing program in response to the 2008-09 financial crisis. Powell said in March 2019 that the Fed's goal would be to shrink the balance sheet to "the smallest level consistent with conducting monetary policy efficiently and effectively."

However, the balance sheet continues to grow as the Fed forges on with its monthly securities purchases. If the Fed completely winds down these transactions by the end of next year, economists forecast another $1.4 trillion could be added to the balance sheet, bringing its total holdings equivalent to about 38% of GDP. Powell indicated that the optimal size of the balance sheet should be about 16% of GDP.

Still, Fed officials are not publicly discussing plans for balance sheet reduction as the path of post-pandemic recovery, and the potential timeline and structure of tapering bond-buying, have taken precedent.

Market disruptions

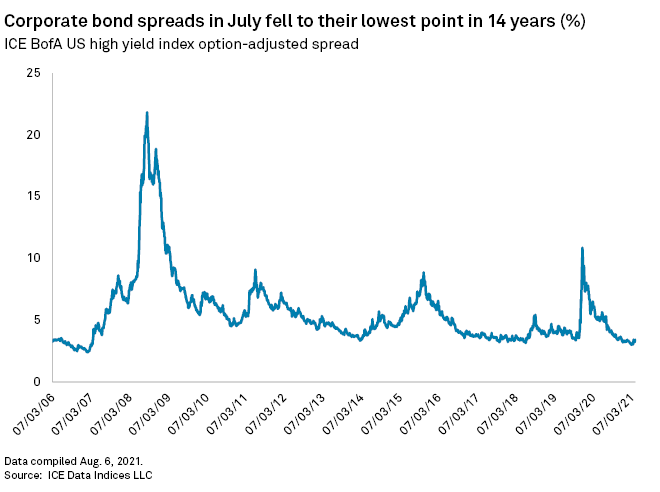

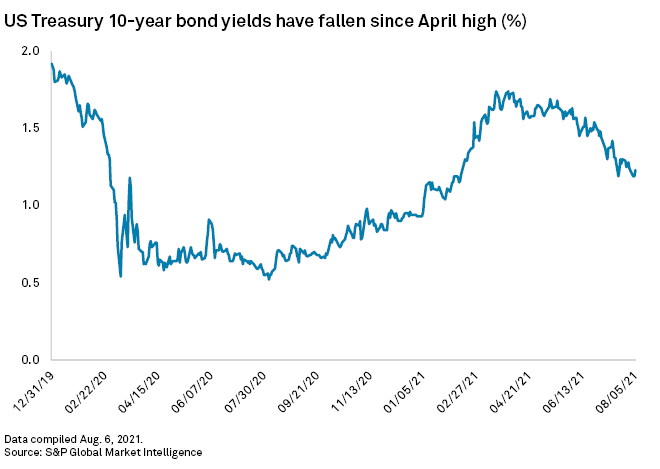

Since the Fed bond-buying spree began in 2020, yield spreads on benchmark corporate high-yield and investment-grade bond indexes hit their lowest points since before the 2008-09 crisis. These spreads, which are the difference between the interest rate premium of corporate debt holdings and safer U.S. government bonds, have narrowed as Treasury yields fell to new lows.

The benchmark U.S. Treasury 10-year yield, which fell as low as 1.19% in July, would be trading at roughly 2.25% if the Fed was not continuing to buy $120 billion in securities each month, said Andrew Brenner, head of international fixed income at NatAlliance Securities.

"I've never seen a Treasury market as illiquid as it's been," Brenner said in an interview. "The Fed is just buying way too much. Way more than the Treasury market can fathom."

The Fed's initial asset purchases from March 2020 through May 2020, at the height of pandemic lockdowns, helped calm the Treasury market at the time but has since had little benefit for the economy, said Mickey Levy, chief economist for the Americas and Asia at Berenberg Capital Markets.

"The economy would have rebounded without the QE had the Fed maintained zero rates but unwound its asset purchases earlier," Levy said in an email.

The large balance sheet created easier financial conditions, higher asset prices and less credit discipline as "marginally viable" companies, or companies with relatively low earnings and high debt, were able to hang on due to the Fed's market intervention and subsequent low interest rates, Ratings' Gruenwald said. Reducing the Fed's balance sheet will produce a long-term good for the economy, allowing rates to move more and those marginally viable firms to fail and new firms to enter.

"That's good for dynamism, it's good for productivity and it's good for growth," Gruenwald said. "All of that has been suppressed while we've had the Fed going big into the bond market."

Gruenwald said the Fed should begin to gradually withdraw from the bond market after it tapers its bond purchases and the central bank lifts its benchmark interest rate from near-0%. The Fed is expected to unveil its tapering plan before the end of the year.

"The idea is not to pull the plug on that tomorrow but to gradually have the Fed withdraw from that market, and rates will rise, spreads will rise," Gruenwald said.

Some discussion of balance sheet reduction is expected to take place over the next few rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee meetings later this year as Fed officials discuss the plan to start tapering bond purchases, said Gennadiy Goldberg, a senior rates strategist at TD Securities.

Goldberg said "the jury is still out" on just how much of the balance sheet the Fed may plan to run off, adding that its recent announcement to put a repurchase agreement facility in place would give the central bank a backstop in case reserves become scarce. The facility will take in certain securities in exchange for one-day loans of cash at a rate of 0.25%.

Brenner with NatAlliance expects the Fed will ultimately decide to reduce its balance sheet by $500 billion to $1 trillion per year over two to three years, ultimately settling between $4 trillion and $6 trillion.

"We're never going back to $800 billion," Brenner said. "The days of a sub-$1 trillion balance sheet are over."