S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

6 Jan, 2021

By Richard Martin

|

Levels in Lake Powell, a wonder of the U.S. Southwest, have been falling for years. Source: John Wang/DigitalVision via Getty Images |

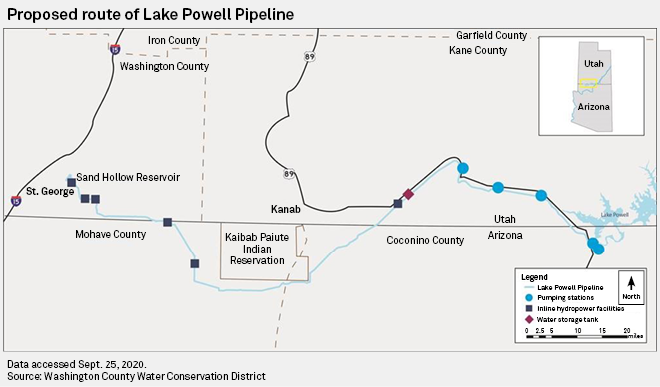

West of Lake Powell, along the Utah-Arizona border, lies a sparsely populated territory of high desert, deeply scored canyons and barren mesas. Here, Utah officials want to build a 140-mile-long pipeline to bring precious Colorado River water west to the thriving town of St. George, in the state's far southwestern corner.

In an era of perennial drought, when the future of the Colorado River watershed, the lifeline of the U.S. Southwest, is the subject of fierce debate in state capitols across the region, the idea of bringing more than 26 billion gallons of water a year to a community of fewer than 200,000 people on the edge of the Mojave Desert strikes many as folly. To officials in Washington County, of which St. George is the county seat, though, it is a critical resource for the future.

Currently the county has one primary source of water, the Virgin River, said Todd Adams, director of the Utah Division of Water Resources, and more will be needed in the coming decades.

"They only have one water source, and they have potential vulnerabilities with the Virgin River," Adams said in a recent interview. "They need a second reliable source."

What's more, St. George, a bedroom community about 120 miles from Las Vegas with more than a dozen golf courses, lavish resorts and a high percentage of retirees, is expected to continue to grow rapidly through mid-century. To serve all those new arrivals, and all those fairways, more water will have to be imported, say local and state officials.

"Based on the population growth projections for Washington County through 2060, it's expected to triple in size to over 500,000," said Adams. "And with that growth, additional water sources will be needed."

The problem is that taking water from one part of the Colorado River watershed diminishes the water available for other parts. And long before St. George reaches its ultimate population level, there may not be enough to go around.

Undead

Approved by the Utah state legislature in 2006, the Lake Powell Pipeline has become one of what opponents and environmentalists have dubbed "zombie water projects": proposals for diversion and transportation in the Colorado River watershed that face significant opposition and may never get built, but that refuse to die.

The pipeline was originally pitched as a source of water and power generation. The initial plan called for a large hydropower generating station along the route and a reservoir for pumped energy storage, but those elements were scrapped to reduce the environmental impact of the overall system, according to Karry Rathje, a spokesperson for the Washington County Water Conservation District. The line will still include six smaller inline hydropower facilities, to manage the water pressure and to reduce the electricity load from the pipeline on the regional grid. Those stations will total 85,000 MWh of generation annually, at full capacity; the full project will consume around 317,500 MWh, making it a net consumer of 232,500 MWh a year.

Reducing the amount of water in Lake Powell, though, could affect electricity production at the two major downstream hydro stations on the Colorado, at Glen Canyon Dam below Lake Powell, built in 1964, with 1,312 MW of generation capacity, and the two plants at Hoover Dam, built in 1936, with a combined capacity 2,078 MW, below Lake Mead. Both dams have become symbols of the 20th-century conquest of the Southwest and of the human depredation of the Colorado River ecosystem. Glen Canyon, in particular, was controversial from its conception; environmentalists today loudly demand its removal.

Together, the two dams produce enough electricity to feed roughly 630,000 homes across the region. Because hydropower generation is dependent on the volume of water stored in the reservoirs, as the levels of lakes Mead and Powell fall, electricity production will follow. Lake Powell has been below its average annual elevation every year in this century, according to data collected by Western Resource Advocates; in 2018 the difference was more than 30 feet.

Electricity production from all three facilities has fallen slightly in recent years, and water experts believe the future could be far worse.

"Higher temperatures and altered precipitation patterns" — i.e., the effect of global climate change — are expected to reduce streamflows in the basin by up to 11% by 2075, according to a 2013 white paper by Aaron Thiel of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee's Center for Water Policy. "These factors, combined with increased summer evaporation rates, could reduce reservoir storage by as much 10-13 percent, and ultimately reduce electricity generation by 16-19 percent in the Colorado River Basin."

Reduced electricity from hydropower could be only one of the obstacles facing big water-diversion projects like the LPP, as policymakers face the new drier, hotter era in the Southwest.

Business risk

Governed by a complex web of agreements and water rights stemming from the Colorado River Compact of 1922, water use in the basin has long outstripped the actual water available. As the climate warms that gap is sure to expand.

A 2017 paper in the journal Water Resources Research, by Bradley Udall of Colorado State University and Jonathan Overpeck of the Colorado River Research Group, found that "As temperatures increase in the 21st century due to continued human emissions of greenhouse gasses, additional temperature‐induced flow losses [in the Colorado River] will occur." Those losses could exceed 20% below the 20th-century average flow by mid‐century and 35% by 2100.

And they could be devastating to the region's economy. According to a 2014 study that was produced by Arizona State University's Seidman Research Institute and commissioned by Business for Water Stewardship, a non-profit organization, the Colorado River supports $1.4 trillion in annual economic activity and 16 million jobs across the seven states of the basin. Water from the river is essential to at least half the gross economic product in each of those states, including 65% in New Mexico and 87% in Nevada, the economists found. A drop in available water of only 10% would endanger some $143 billion in economic activity in a year.

Businesses everywhere are increasingly vulnerable to the risks presented by inadequate supplies of clean water. The 2019 Global Water Report produced by CDP, a nonprofit organization focused on the environmental impacts of companies, investors and governments, found that, worldwide, the total business value at risk due to water shortages and water pollution reached $425 billion. In the U.S. Southwest, that risk grows more acute with each year of persistent drought.

In many ways major water projects, such as the Colorado River Aqueduct, completed in 1941 to bring water to Southern California, and the Central Arizona Project, delivering water to Phoenix and Tucson since completion in 1994, have defined the civilization of the region. In the 21st century, though, the federal government has turned off funding for massive water projects, and multibillion-dollar diversions like the LPP look increasingly like anachronisms.

Despite being identified in a June 2020 executive order from the Trump administration as among the infrastructure projects that should be pushed quickly through the environmental review process, the LPP has sparked near-universal opposition from the other six states of the basin. That opposition crescendoed in September with a letter to the Secretary of the Interior from a coalition of state water agencies and governors' offices in Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Wyoming demanding that the project be paused or abandoned.

"We write to respectfully request that your office refrain from issuing a Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) or Record of Decision (ROD) regarding the Lake Powell Pipeline until such time as the seven Basin States and the Department of the Interior are able to reach consensus regarding outstanding legal and operational concerns raised by the … project," the letter stated.

A week later state officials requested an "extended timeline" from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to complete a review of the thousands of comments responding to the project's environmental impact statement. Construction is expected to start in the late 2020s, according to Rathje.

Building it, opponents argue, would contradict the consensus reached in May 2019, when the seven basin states and federal officials agreed on a "Drought Contingency Plan" through 2026 that established voluntary conservation measures and reduced the amount of water pledged to the lower basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada. Water diversion cutbacks began in 2020 in the lower basin. The Lake Powell Pipeline plan, opponents argue, simply ignores this new reality.

"The whole system is declining — it's a diminishing product that we own," said Zachary Frankel, executive director of the Utah Rivers Council, which has opposed the project since its inception. "Colorado River water users are going to have to start a debate to figure out who's actually going to give up water, and right now it's a tug of war."

Subsidized water

In southern Utah that debate is complicated by a range of factors with origins in the economics and politics of water in the West.

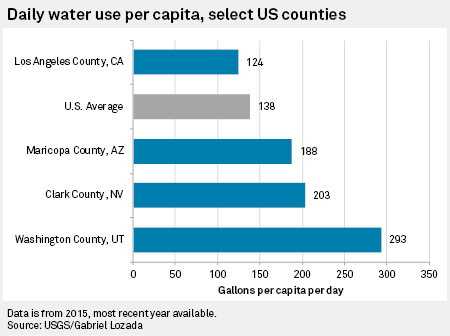

People in Washington County use around 300 gallons of water per capita per day, according to the most recent figures from the U.S. Geological Survey, more than twice the national average and 90 gallons more per capita than residents of Las Vegas, a city of nearly 650,000. And they get their water cheaply: water rates in the county average around $1.50 per 1,000 gallons, less than half of what Las Vegans pay and way below the $5/1,000 gal. that Denverites pay.

Zach Renstrom, the general manager of the Washington County Water Conservation District, disputes those numbers, saying that the state of Utah includes evaporation from reservoirs and re-used water in its water-use calculations.

"Our citizens don't take more showers or flush their toilets more or have more vegetation," said Renstrom. "It's really just the methodology."

Still, simple economics indicate that if people in southwest Utah paid more for their water, they would use less.

"Water use in Utah is subsidized, mostly by property taxes," said Gabriel Lozada, an associate professor of economics at the University of Utah who has extensively modeled the Lake Powell Pipeline project. "So people in urban areas don't see what the right price of water is. Unsurprisingly, Utah urban dwellers use a lot more water. The price of water we face is way way too low."

And Washington County residents will eventually have to pay for the new pipeline, after the state fronts the construction costs. That, says Lozada, in turn would raise water rates — thus obviating the need for the pipeline as residents use less water. The possibility of rising prices leading to more conservation, and thus less demand, has not factored, at least publicly, into the developers' considerations.

"In many scenarios it's possible for Washington County to raise rates enough to pay back the cost of the pipeline," said Lozada, "but they'd be so high that demand for water would be so low that no one would want to buy the water in the pipeline."

Renstrom claims that Lozada and other opponents have an underlying agenda.

"I think a lot of it is flat-out anti-growth," he said. "What I hear, when people say it's going to cost too much, at the end they're asking, 'Do we really want all these people moving here?' There is a strong anti-growth vocal minority."

A shrinking pie

Similarly unstated is another incentive to build a new pipeline now: Utah has the right, under existing agreements, to take more water out of the river than it currently uses. In theory the state has an allocation of 23% of the average flow of the Colorado. Current annual use totals much less than that. Many observers say that building the Lake Powell Pipeline is like trying to stick a straw in a milkshake before others drink it up.

"The state of Utah agreed to a certain size of a slice of the overall pie," said Jack Schmidt, a professor of watershed sciences at Utah State University who holds the Janet Quinney Lawson Chair in Colorado River Studies. "Therefore they have unused water. They have the right to build a new pipeline because they still have water to develop. But that only applies if you're taking a slice from the size of pie that existed in the middle of the 20th century. It has nothing to do with the size in the 21st century, or going forward."

The complicated law of the river, supporters counter, gives Utah higher priority or more "senior" rights than other offtakers.

"We're not just getting rights in 2020," said Renstrom, the water conservation district manager. "These are older water right we'll be using, so if there are additional calls on the river, the later rights will be cut off before ours."

Those distinctions could well become moot, depending on the negotiations to establish a drought plan more permanent than the contingency plan agreed to in 2019. Preliminary talks are already underway. If Utah and other Upper Basin states agree, or are compelled, to reduce their allotment of water, it's unlikely that a major project like the LPP would go forward, which is another reason the proponents want to break ground soon.

The argument over the Lake Powell Pipeline is a proxy for a larger debate about the future of the economy and society in the West, between competing visions of unlimited growth and boundless prosperity, on the one hand, and a new era of scarcity, conservation and more modest expectations on the other.

The biggest consumer of water in the Southwest, by far, is not cities like St. George but big agriculture. Since the early 20th century farmers have been growing water-intensive crops like alfalfa and cotton in the desert, using groundwater and Colorado River water. That era could be coming to a close. As the region urbanizes, converting farmland to towns, average water use goes down. Even a golf course uses less water than an alfalfa farm. A 2015 report on Utah's future water resources and needs by the state's Legislative Audit Division found that the Utah Division of Water Resources "understates the growth in the water supply when estimating Utah's future water needs."

"The division has not attempted to identify the incremental growth in supply that will occur as municipalities develop additional sources of water," the auditors wrote. "That additional supply will mainly come from agriculture water that is converted to municipal use as farmland is developed."

At the same time, municipal water districts in the West, such as Las Vegas, are actually using less water per capita as their populations grow.

"The widespread presumption that population growth means growing water demand drives much of the politics of water planning in the Colorado River Basin," write Eric Kuhn, the former general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservancy District, and John Fleck, director of the University of New Mexico's Water Resources Program, in their 2019 history of Colorado River management, Science Be Dammed. "But it is wrong. Simply put, we are consistently using less water. In almost all the municipal areas served with Colorado River water, water use is going down, not up, despite population growth."

That means the fundamental presumption at the heart of the Lake Powell Pipeline — that in order to grow, Washington County needs more water from the river — is likewise flawed. And it offers hope that as the climate warms and the region dries, it's possible to forge a new relationship between the Colorado River and the communities that depend on it.

"We have been getting it wrong for a century," write Kuhn and Fleck. Time to get it right is growing short.