Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

19 Jan, 2022

By Jack Hersch

Debt and equity market participants have been uneasy about the potential impact of the U.S. Federal Reserve raising its federal funds rate target, perhaps as soon as this March. But judging by how the markets reacted to previous rate hikes, that concern may be misplaced. It calls for a closer look.

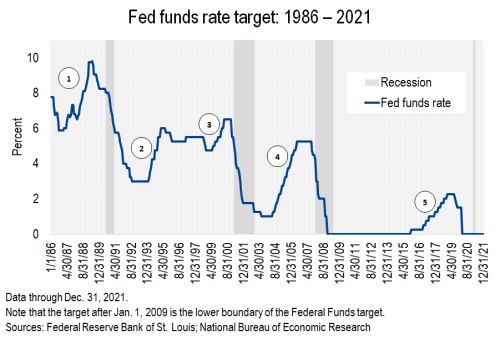

Since the mid-1980s, the U.S. Federal Reserve raised the Fed funds rate for extended periods five times: in 1987-1989, 1994-1995, 1999-2000, 2004-2006 and 2015-2018. Equity markets rallied during each of those periods, high-yield rallied 80% of the time and leveraged loans, tracked by the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan index only since 1997, rose during the last three rate hikes. Note that equities are represented by the S&P 500 and high-yield by the ICE BofA U.S. High Yield Index.

Generally speaking

Market nervousness has been exhibited in 2022 by lower equity and high-yield markets, and higher 10-year U.S. Treasury yields (perhaps not surprisingly, given their variable-rate structure, leveraged loans continue to rise). The behavior is not unique to this year: One month into the last five rate-hike periods, equities were lower four times, while high-yield and leveraged loans were lower around half the time.

MORE DEEP DIVES: Do low yields, rising inflation foretell economic slowdown?

But that early weakness almost always gave way to rallies: equities were higher at the end of all five periods, leveraged loans were higher after the three periods that were tracked, and high-yield was higher four times and down just 3% the fifth. It is also notable that the economic braking action of a rising Fed funds rate in those periods did not immediately translate into declines in gross domestic product. Although recessions followed four of the rate-hike periods, the official start of each was, on average, more than one year after the final hike.

In the sections that follow, LCD looks at leveraged loan, high-yield and equity returns at four points during each of the five prolonged Fed rate-hike periods: 1) the month-end before the first rate hike; 2) the month-end of the first rate hike; 3) the month-end of the last rate hike; and 4) the month-end 12 months after the last rate hike.

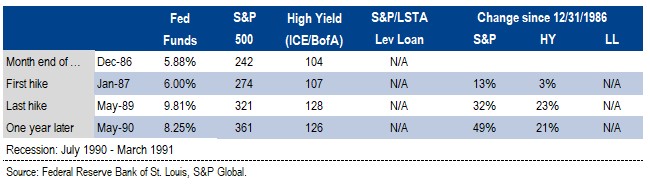

Hike Period 1: 1987-1989

The Fed funds rate had been declining steadily since peaking above 11% in 1984. The Federal Reserve began lifting the rate in January 1987 in a move that did not end until May 1989 (with a brief exception around the October 1987 stock market crash). That eventually led to the 1990-1991 recession.

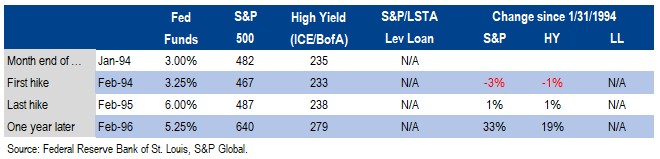

Hike Period 2: 1994-1995

In February 1994, the Federal Reserve raised the Fed funds target by 0.25 point, to 3.25%, initiating a series of raises that continued through February 1995, taking the rate to 6%. While 1994 was a generally difficult investing year, with a major sell-off in government bonds and weakness in equities and high-yield, no recession ensued, and markets eventually turned much higher.

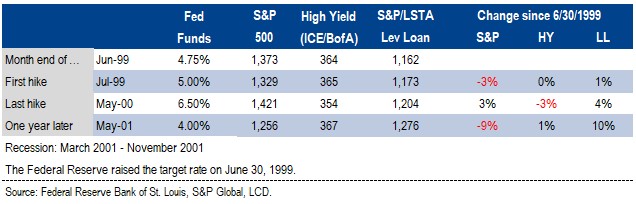

Hike Period 3: 1999-2000

After allowing the Fed fund rate to drift down to 4.75%, from 6%, the Federal Reserve in late June 1999 began a new series of hikes that continued through May 2000. By the last rate hike, the Nasdaq composite was on its way to losing more than 80% over two years, the S&P 500 would eventually surrender almost 50%, and high-yield would give back about 14%. Leveraged loans would appreciate over that time, albeit on a bumpy trajectory. Despite the eventual damage, the S&P 500 rose during the rate hike period, as did leveraged loans, while high-yield slipped by 3%. The U.S. economy declined between March and November 2001.

Hike Period 4: 2004-2006

A series of Fed fund rate rises began roughly two years after the first bear market of the new century bottomed. Starting in July 2004, the Fed raised rates steadily for two years. After the final hike in June 2006, markets continued trekking north. High-yield peaked in the spring of 2007, while equities topped out in October 2007. Subsequently, Lehman Brothers collapsed and the Great Financial Crisis struck.

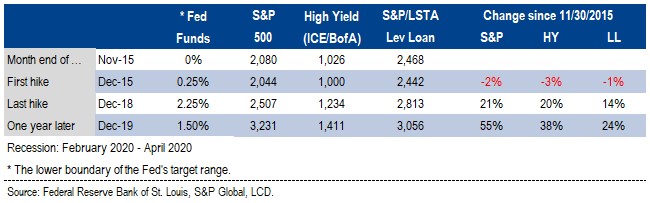

Hike Period 5: 2015-2018

Following the Great Recession, the Fed held fed funds near zero for seven years before gingerly beginning to raise its target in December 2015. The target rate range — the Federal Reserve shifted in December 2008 to setting a target range from a target rate — rose steadily until December 2018, after leveraged loans, high-yield and equities had all turned significantly lower that autumn. Eventually, markets renewed their rally until the pandemic-driven collapse in March 2020.

Is it different this time?

Throughout market history, both bulls and bears have occasionally been tempted to say, It's different this time. But differences often are in the eye of the beholder. While there may be many differences between the five most recent rate-hike periods and the one we appear about to embark on, two may have influences on current markets that are worth contemplating.

The first is inflation, which is rising faster now than at any time since the early 1980s. Inflation has risen (and ebbed) numerous times since then, but never to the levels now being recorded. It might be a difference-maker.

The second is valuations. Measured by trailing price/earnings ratios, the S&P 500 is more expensive now than at the start of any of the other rate-hike periods, except for 1999-2000. The S&P P/E ratio is around 30, while preceding the June 1999 rate hike, the ratio was around 33. P/E ratios hovered around 19 as of January 1987, February 1994 and July 2004, and 22.7 as of December 2015, according to data from the Nasdaq's website.

Private equity EBITDA multiples are also higher now than at any time in the past. They currently average above 12x, about 50% above the multiples of the mid-2000s, according to S&P Global Ratings.

In a 2019 Wall Street Journal article, columnist Mark Hulbert noted a widely held belief that "low rates justify above-average price/earnings ratios." Presumably, that would hold for private equity multiples as well. Hulbert's article pointed out that the theory, however, may not be supported by history.

Regardless of the theory's validity, higher Fed funds rates eventually lead to higher capital costs. For investors, both stronger operating earnings and higher valuation multiples can offset the negative impact of rising rates. If not, then it might very well be different this time.