Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

6 Apr, 2021

By Jack Hersch

Inflation has not been a lead story in the U.S. financial press for many years. But with the Treasury yield curve steepening, commodity prices rising and stimulus money filling consumer pockets, it is now a front-page topic. The high yield and leveraged loan markets have encountered only brief bouts of inflation in their relatively short histories, and never at the levels experienced in the 70s and 80s. In the absence of institutional memory, how might those asset classes react if inflation were to take off in today's markets?

Inflation fuel

|

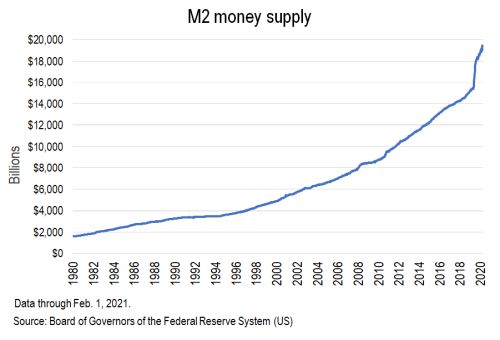

Oxford Economics estimates that from the onset of the pandemic through January 2021, U.S. households saved $1.8 trillion more than they otherwise would have as lockdowns and shutdowns pushed money into savings for lack of discretionary reasons on which to spend cash. The new $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan is now adding more to that sum.

|

President Joe Biden's $2 trillion in proposed infrastructure spending and the possible forgiveness of much of the $1.5 trillion in student loan debt add fuel to this potential inflation fire.

Classic expectations

Classic economic theory holds that the level of inflation invariably follows expectations of that level. But expectations vary. Pete Cecchini, founder and chief strategist at AlphaOmega Advisors LLC and a former chief strategist at Cantor Fitzgerald, takes a line similar to the Fed, saying, "The U.S. will experience sudden demand and associated inflation as people spend their savings and stimulus and as the global supply chain struggles to keep up. But then we will return to low growth."

He points out that the U.S. economy was perhaps heading toward recession at the end of 2019, before the pandemic drove the country there faster than anyone had anticipated. So once the current ocean of cash is spent, Cecchini believes conditions similar to those in late 2019 will return.

More Deep Dives: Airlines Daily Cash Burn | Oil & Gas Volatility/Risk

S&P Global Ratings said in a recent report that it too believes inflation will rise only into the low- to mid-2% range and will be "transitory," not lasting past the end of this year before returning to its "previously low rates."

While the Fed, Cecchini and S&P Global Ratings, among others, expect only a modest inflation bump, Bill Gross, co-founder of PIMCO, takes a more aggressive tack, saying recently in an interview with Bloomberg News that he sees inflation "screaming higher," framing that more specifically as "a 3%-4% number ahead of us."

Credit vs. capital

At the same time, Fridson notes that capital availability might be harmed if high yield investors, particularly pension funds and insurance companies, cannot see a way to match their cost of funds against high yield issuance. That could force an increase in high yield coupons, closing the market window to more highly leveraged borrowers and driving those turned away to the leveraged loan and private debt markets.

In fact, Fridson feels the leveraged loan market will do well in a high-inflation world. "The adjustable rates of leveraged loans would be attractive and would siphon off investment capital from high yield," he says. "Loans would be the winner there."

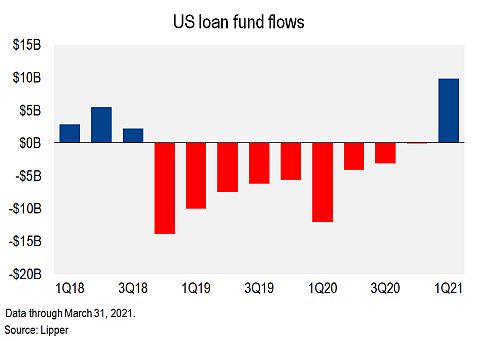

That may be already happening. John Cortese, managing director and co-head of U.S. credit trading at Barclays, is seeing retail flows moving "notably into the leveraged loan market." Retail had almost completely abandoned leveraged loans in the market rate-driven "flare-up" at the end of 2018, he notes, but retail buyers are now returning to the floating-rate asset class.

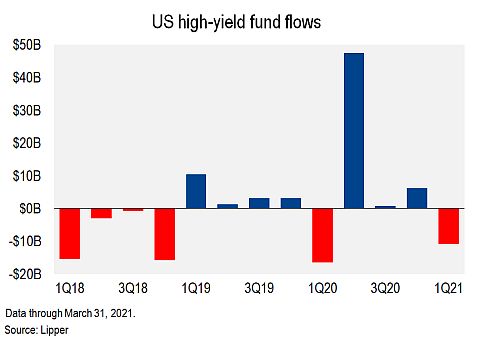

Lipper data supports Cortese's observations. While funds flowed out of U.S. loans every quarter from 2018's fourth quarter through calendar year 2020, 2021's first quarter saw a $10 billion inflow. Meanwhile in high yield, three consecutive quarters of inflows were followed by an $11 billion outflow in the 2021's opening quarter.

|

|

Dan Zwirn, chief investment officer of asset manager Arena Investors LP, expands on Fridson's viewpoint, saying, "In variable rate structures [such as leveraged loans], you would be partially protected from a rise in risk-free rates that would likely come if inflation were to present too much of a problem."

But the advantage of variable rates goes just so far. Zwirn hypothesizes that a rising risk-free rate world "would mean greater pressure to reduce duration, greater pressure on industries where capex is a material use of EBITDA, greater pressure on add-backs, and ultimately greater pressure on acquisition multiples. The model would seem to break in that scenario." Zwirn goes on to explain that buyers probably cannot pay, say, 12 times cashflow and still deliver desirable returns to their investors in a 5% risk-free world.

Another byproduct of higher interest rates, according to AlphaOmega's Cecchini, is a potential rise in savings rates among consumers, which could, in turn, be a drag on consumer demand, leading to a repeat of the 1970s stagflation phenomenon: high inflation, resultantly high yields, but with a stagnating economy.

Fridson concurs, noting that while inflation is almost always associated with good times and a strong economy, 70s stagflation proved to be the exception to that rule.

Bond math

But Schachter adds that "the compression will be not linear." Lower-rated credits historically compress more than higher rated credits in periods of strong GDP growth and rising rates as their businesses will, in general, derive greater benefit from the economy's strength.

The Barclays strategist also points out that the post-financial crisis floor in option-adjusted spreads is around 300 basis points, while roughly 240 bps is the all-time tight for the high yield market. At current spreads there is room for compression, but not much, if history is a guide.

Srikanth Sankaran, managing director and credit strategist at Morgan Stanley, believes that even if inflation ticks up higher than currently expected, "it should be reflected in stronger corporate earnings," at least initially, as companies will pass on higher costs to consumers.

Sankaran believes that investment grade issuers should fare worse than high yield companies, as greater spread cushion and shorter duration will benefit high yield bonds. "The high yield market should be attractive to investors," he says. If inflation overshoots because policy rates are low, he expects that higher-quality high yield and investment grade will be relatively hurt and "debt lower down the credit curve will be the beneficiaries."

Push and pull

AlphaOmega's Cecchini anticipates that the U.S. will see both "cost-push" and "demand-pull" inflation. The demand-pull will derive from the savings and stimulus cash being put to work. The cost-push will emanate from the supply shock caused by the ongoing supply chain disruption as the global logistics system is challenged by the pandemic.

Cecchini believes a cause of cost-push inflation in the past was wage-price spirals — consumer goods prices rose, triggering unions to fight for wage increases, which led to further price increases, which led to new union demands for further wage increases. He expects this will not be as much of a factor this time.

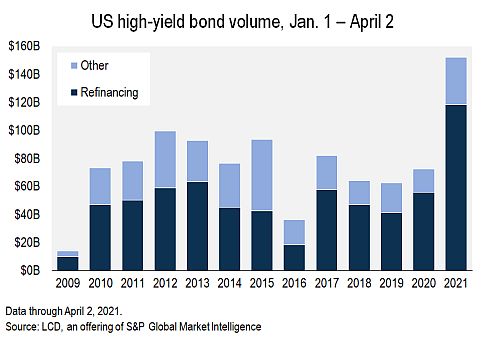

In theory, demand-pull inflation produces higher corporate profits as revenues rise ahead of costs. For that reason, Schachter, of Barclays, believes that from an operating standpoint, demand-pull inflation will ultimately have little impact on the high yield market, arguing that the increased earnings and commensurately higher cash flows will inure to equity. He adds that while healthier valuations and cash flow metrics might normally open the door to refinancing at lower coupons, with enough inflation the commensurate rise in Treasury yields may hold that door shut.

|

On the other hand, Schachter points out that cost-push inflation "is the more pressing risk for markets because it stresses margins" particularly for operating companies, as wages and raw material costs rise ahead of prices. More granularly, Schachter believes corporate consumers of commodities, such as oil-based products and metals, could be harmed by high commodity prices, but he points out that "the scale is really what matters" in trying to gauge the definitive impact on high yield issuers.

Unequal treatment

Fridson believes homebuilders is "a sector investors probably want to avoid," with higher interest rates making homes less affordable, on top of higher construction costs from higher wages and lumber prices that would be passed through to buyers.

Barclays' Cortese notes that CCC-rated companies have already been outperforming as they are directly correlated with growth. Going forward, he sees high yield market players focusing on cost inflation, singling out freight costs and oil prices as two line-items that could negatively impact margins.

He believes companies with higher operating leverage are likely to benefit most, namely companies with "more fixed costs and quote/unquote higher torque to top-line improvement." More specifically, in the high yield market Cortese is seeing buyers of the bonds of companies in chemicals, energy, metals and mining, in general companies that will benefit from an rising rate cycle, whether it is "a growth story, an inflation story, or both."

But Fridson suggests that the impact of inflation on commodity producers, such as metals/mining and energy producers, will be nuanced. "They might be in their own unique cycle," Fridson says, one that moves independently of inflation.