S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

7 Sep, 2022

|

|

Fears of COVID-19 infections have waned in recent months for many American workers. That has not resulted in a massive return to the workforce, though — a fact that worries many economists looking at the long-term future of the U.S. economy.

|

A structural decline in the U.S. labor participation rate represents a long-term drag on U.S. economic growth as shifting demographics and a decline in immigration limit the potential workforce.

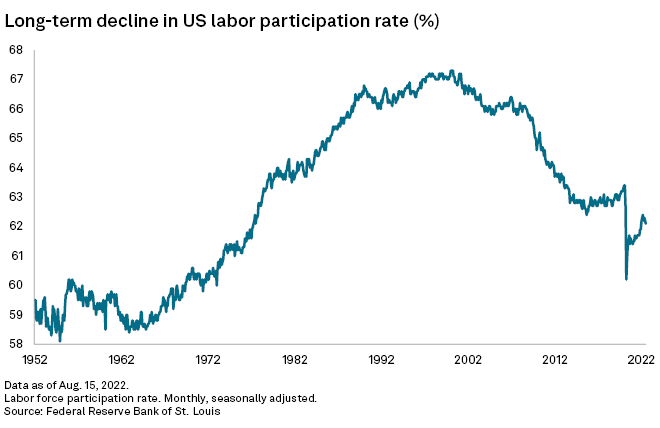

The percentage of working-age Americans either employed or looking for work sank from 63.4% to 60.2% during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. While that figure has recovered somewhat to 62.4%, the longer-term outlook is for further decline. U.S. workforce participation, in fact, has been falling steadily for more than two decades since peaking at 67.3% in 2000.

Early retirement and fears of catching COVID-19 in the workplace kept older workers at home, while expensive childcare and a lack of enthusiasm for low-paid, low-skilled jobs in the service economy have put off a cross-section of society. Annual population growth stalled at 0.1% in 2021, the lowest rate in the country's history, so a falling participation rate means the U.S. faces long-term constraints to the labor supply that reduce the potential for growth in a country that has 11.2 million job openings and only 6 million people currently looking for work.

The difficulties in drawing Americans back to work combined with a reduction in immigration — partly due to COVID-19 and partly due to policy — are "starving the labor market for new workers," according to Chris Varvares, vice president and co-head of U.S. economics at S&P Global Market Intelligence.

"So, when you wonder why there are so many job openings, the economy is attempting to grow with very slow growth in the labor force," Varvares said.

Grinding down

Demographic changes mean the trend will likely worsen. While Market Intelligence expects a short-term recovery in the labor participation rate to 62.7% as the lingering effects of COVID-19 fade, the rate is forecast to grind down to 60.7% by 2035.

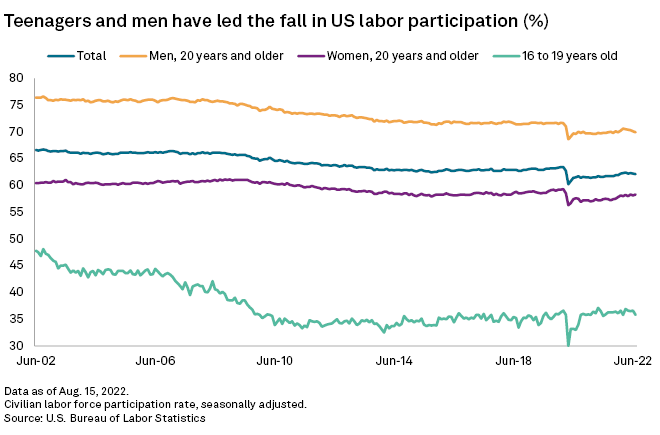

Part of the long-term decline is due to more teenagers staying in school. The labor participation rate of 16-19-year-olds fell from over 48% in 2002 to 37.7% currently. Participation is dwindling at the other end of the age range, as well, as the baby boomer generation reaches retirement age. The demographic surge caused by high birth rates in the '50s and '60s — and the relative affluence of many of those people — means that an unusually large percentage of the working-age population is in a position to retire early. Meanwhile, reduced birth rates in subsequent decades have slowed the pace of younger people coming into the workforce to replace their grandparents.

This dynamic will not last forever. As the distribution of ages in the labor force smooths out, more workers will likely remain on the job; but these trends will persist for another 10-15 years until the boomer and Generation X anomalies are cleared out, pushing the participation rate lower, according to Wendy Edelberg, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and director of The Hamilton Project, an economic policy initiative within the institution.

"If labor force participation stays depressed, that means that even as the economy in the U.S. begins to bounce back, there are not going to be the workers there to fulfill that demand, and that's going to drive up prices in an unwelcome way," Edelberg said.

Short-term recovery will bow to demographics

The U.S. labor market has between 3 million and 3.5 million fewer people than it would have had without the pandemic, according to The Hamilton Project.

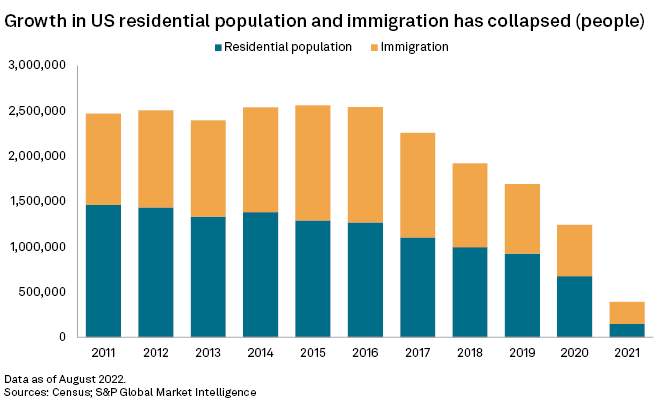

Although COVID-19 was most fatal for older people in retirement age, an estimated quarter of a million deaths occurred in the working age range of 18-64. Meanwhile, COVID-19 accelerated a decline in immigration from around a million a year to less than a quarter of that.

As the labor supply shrank, the pandemic also reduced the participation rate of working-age adults.

About 2.6 million more people than expected retired in the period since COVID-19 reached the U.S., according to research by Miguel Faria-e-Castro, a research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. At the same time, many people who are immunocompromised or have vulnerable family members remain reluctant to return to places of work where they could pick up a virus that is still killing about 500 people a day.

This phenomenon is expected to reverse, for a time.

"Higher wages, better job opportunities and the rising cost of living will bring workers back into the labor force as savings erode, even as overall job growth slows," Ellen Zentner, chief U.S. economist at Morgan Stanley, wrote in an August 5 research note. The bank expects the temporary increase in labor force participation to be driven by prime-age workers.

Historically, the labor participation rate has, to a degree, correlated with economic growth. The downward trend was interrupted between 2016 and 2020, a period when the unemployment rate was low, forcing wages to rise and enticing people back to work.

"When there are rising wages, some marginally attached workers will reenter," said Varvares of Market Intelligence. But the participation of men aged 20 and up has surprised many analysts by declining in recent months, even as wages rose.

Jobs gone forever

Among the reasons that men have fallen out of the workforce is the impact of the opioid crisis, which has ripped through the country, claiming over 100,000 lives in drug overdoses in the 12 months ended in April 2021 and leaving many more grappling with addiction. At the same time, industries that once offered large numbers of less-educated men relatively high-paying jobs have shrunk or evaporated altogether. The coal industry, for example, lost 30,000 jobs between 2010 and 2020, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Most of those positions are not coming back.

"There are plenty of jobs for those who are looking, just not the jobs that once were there, especially the high-paying manufacturing jobs for less educated men," Anne Case and Nobel prize-winning economist Angus Deaton wrote in their 2020 book Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. "This is why so many people are not looking for work."

Should wages rise high enough, and the pressure of the cost of living prove burdensome enough to drive the level of men in the workforce back to even pre-COVID-19 levels, it would mean hundreds of thousands more people in the labor market.

Particularly for working-age men without a university degree, labor participation "is a big deal," Edelberg said. "If that recovered, it wouldn't solve our labor force problem at any stretch, but it would sure help."

Women have also fallen out of the market. The rise in participation of women was a key driver in the growth of the total U.S. rate from the 1960s through the end of the 20th century, but after peaking around the 2008-2009 financial crisis, that rate has also fallen.

Rising childcare costs have made it more difficult for mothers of young children to work, and women have not been untouched by the opioid crisis. But lessons from abroad suggest that changes to government policy could reverse this trend.

The case of Japan

There is one sure way to recruit more workers: let in more immigrants who will take lower-paid, less-skilled jobs. That would require reforming immigration policy, a goal that has remained elusive for decades.

In Japan, the challenges to labor supply are far greater than in the U.S. A collapse in the birth rate has left Japan with a shrinking and aging population. This forced the country to address its cultural tradition of women staying home rather than going out to work, as well as loosen its historically strict limits on foreign workers.

Japan's female labor force participation has risen from 47.8% in December 2012 to 54.7% in June 2022, boosted by government policy.

"An increase in the flexibility of working style enables females to work as full-time workers, and the government is trying to shift to equal pay for equal work," said Harumi Taguchi, a Tokyo-based principal economist at Market Intelligence. "These have been important policy measures from the Shinzo Abe administration through to the current Kishida administration."

Policies to encourage older workers to stay in employment up to the age of 70 have also been enacted, while new visa statuses are encouraging immigration of lower-skilled workers to boost the labor supply. New immigration policies enacted in 2019 have allowed workers with basic Japanese-language skills to work in Japan for up to five years.

That is the quickest solution to address labor shortages, many economists say: Accept more foreign workers.

Visa issuance in the U.S. collapsed at the start of the pandemic as temporary travel restrictions were established to stop the spread of COVID-19. This reduction, combined with the more restrictive immigration policies enacted under President Donald Trump, reduced the flow of immigrants between 2016 and 2021 by 3.4 million, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

This had profound consequences for labor supply in sectors such as construction, leisure and hospitality.

"Industries that had a larger share of foreign-born workers in 2015 tended to experience more significant increases in job vacancy rates from 2016-2019, suggesting that reduced immigration exacerbated labor shortages," economists Elior Cohen and Samantha Shampine of the Kansas Federal Reserve wrote in a May research paper.

With delays to permits and processing times that plagued the U.S. State Department during the pandemic expected to reverse, Market Intelligence expects immigration to recover, forecasting a rise from 245,000 in 2021 to over 1 million by 2028.

"The easiest thing is sensible immigration policy," Varvares said. "When people come to the U.S. for education and study at U.S. universities, don't make them leave."