Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

25 Jan, 2022

By Taylor Kuykendall and David Hayes

| Once a bustling center of commerce, Whitesville, W.Va., has seen its population contract as coal jobs become more scarce in the surrounding region. Between 2010 and 2019, the Boone County town's population contracted 16.1%, according to U.S. Census data. Source: Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images |

Communities devastated by the collapse of U.S. coal production are also losing their bank branches, removing a catalyst for economic transition when it is most needed.

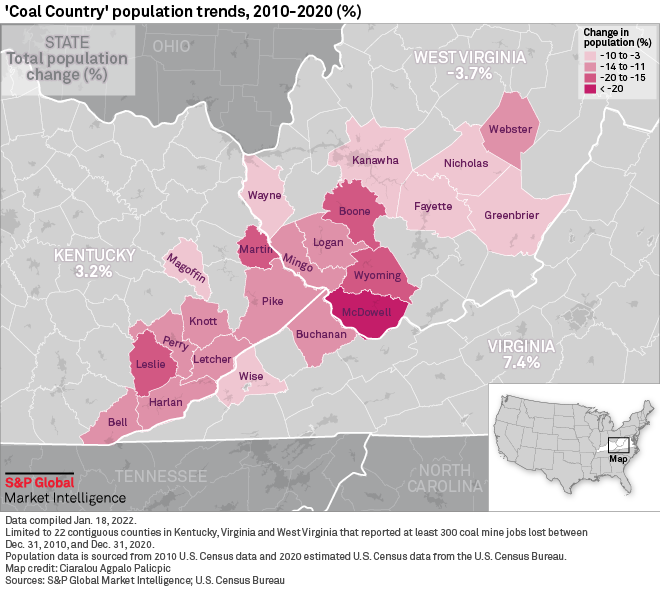

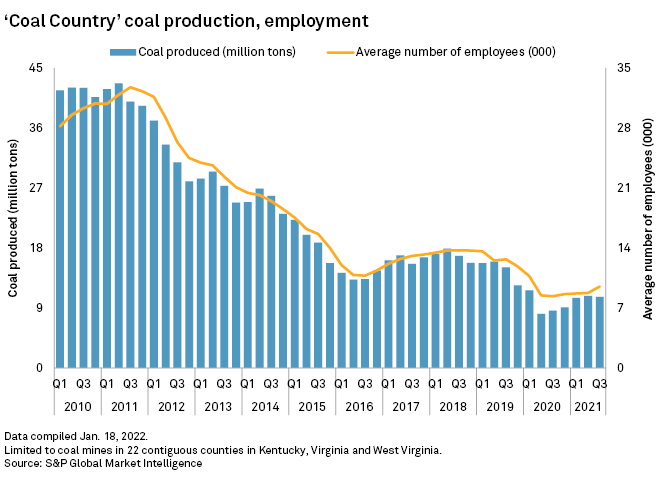

A band of 22 coal mining counties across West Virginia, Kentucky and Virginia have watched coal production decline to a quarter of the level seen just over a decade earlier, and coal jobs have fallen by 69.5%, as the U.S. shifts its power mix to lower-cost, lower-emission generation in the battle against climate change. Without this critical industry, the local population has declined, and banks have responded by shuttering branches.

Since 2010, the number of bank branches that closed in the region has far outpaced new locations, leading to a net decline of 20.7% compared with 17.8% across the U.S. Meanwhile, the country's net bank branch closings hit a record high in 2021. The same counties have experienced a population loss of 10.9%, with some counties losing as much as 23.5% of their residents in the 10 years leading up to 2020, during which the overall U.S. population swelled 7.4%, according to U.S. Census data.

Fewer banking resources could complicate the region's transition to low-emission industries such as outdoor recreation or renewable energy.

"Banking services should be available to all Americans, and it's regrettable that large banks are closing branches in communities that need more access to credit, not less," said U.S. Sen. Cynthia Lummis, R-Wyo., a member of the Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Development who has also seen her state's coal economy contract in recent years. "These are unintended consequences, but they are no less real, and real people are being hurt because of them."

|

|

Local communities, local banks

A dwindling and aging population in the region is the "No. 1 weakness" for banks' strategic planning in southern West Virginia, said Greg Shupe, president and CEO of Pioneer Community Bank Inc.

"That's what keeps me up at night," Shupe said. "The population never rejuvenated itself when coal went through the floor."

Banks in the region historically adapted to down cycles in coal demand, as the local economy has been tied to the black rock for over a century. However, the current decline shows few signs of a rebound, and it is becoming more apparent that coal consumption in the U.S. is on a secular decline as companies shift to lower-emitting power sources. Coal generation accounted for about 19% of utility-scale electricity produced in the U.S. by the end of 2020, down more than half from 52% in 1990.

In the 22 contiguous counties in Appalachia analyzed by S&P Global Market Intelligence, coal production fell from 42.0 million tons in the third quarter of 2010 to just 10.6 million tons in the third quarter of 2021. At the same time, average coal mine employment declined 74.7% to 9,249 employees in the counties, according to U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration data.

The industry's impact goes beyond direct mining jobs. Companies that create engineering plans and provide mining equipment, as well as truckers that haul the coal, are just a sliver of the businesses that depend on mine operations. Regional retail locations, restaurants and banks also benefit from the money that flows into the region. Fewer tons of coal being mined also reduces severance tax collections, and the loss in revenue translates to fewer teachers, county workers and other government positions, said Brian Lego, an economic forecaster at West Virginia University's Bureau of Business and Economic Research.

Shupe, who has banking operations in Beckley, W.Va., and McDowell County, W.Va., said he sees few opportunities in southern West Virginia for a younger generation growing up in the wake of coal's decline. While Shupe said his bank has not struggled in terms of the number of deposits it has seen lately, attracting new customers is difficult.

MCNB Banks Inc. in Welch, W.Va., a self-described "city built on coal," has started to diversify its product offering and geographic footprint into other parts of the state, said John Reed, president and CEO. The bank has roots in McDowell County, W.Va., where average coal employment fell 30.6% from 2010 to 2020. The county saw its population decline 23.5% between 2010 and 2020. What remains, according to estimates from Claritas Pop-Facts 2022, is a population where 24.0% of residents are 65 years of age or older.

McDowell County has posted a higher unemployment rate compared with the U.S. overall nearly every month since December 2009. In over half of those months, McDowell County's unemployment rate topped the national number by 5 percentage points or more. In addition, the county's labor force participation rate was only 28.2%, less than half the 63.4% rate for the U.S. as a whole, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey, 2015-2019.

MCNB maintains branches in its communities to serve those who visit the locations while also marketing remote services to customers who have left the area in an effort to stem the effects of population loss.

"Even though we're losing population there, we are really embedded in that local community," Reed said. "You know, it's just another challenge that you get up and face every day and do the best you can."

Even if coal returned to the relatively high demand seen about a decade ago, the coal region would still be in bad shape, said Peter Hille, president of the Kentucky-based economic development group Mountain Association. Even then, Hille said the region had far too many people unemployed or underemployed. Now, with a dominant industry growing weaker, it is becoming even more difficult to turn things around.

"We have a place that has been, really as a result of all of these outside forces, subjected to long-term persistent poverty," Hille said. "Then you have the predictable results of that, which are reflected in all kinds of things: low-performing school systems, underfunded school systems and underfunded health care."

Aiming for a transition

Still, there is tension between protecting coal jobs and transitioning in the region. The United Mine Workers of America, for example, has called on Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., to pull back from his opposition holding up federal Build Back Better legislation that the union hopes will help replace jobs lost in coalfield communities. The senator has cited multiple concerns with the legislation, including the risk to electric grid reliability if clean energy deployment outpaces the readiness of the technology, but mine workers have often had his ear.

Transition work for affected communities has seen renewed attention under the Biden administration, said Heidi Binko, executive director and co-founder of the Just Transition Fund. The fund started in 2015 to help coal regions affected by the broader global energy transition with grants, technical assistance and other programs to strengthen communities moving away from coal.

"You make a place that's really attractive to live, you make a place that's really attractive for people to come to visit, and more people come, more businesses grow," Binko said. However, many communities lack the resources needed to begin the complex process of applying, and some programs even preclude smaller communities, Binko said.

Miners once collected a salary that was among the highest in the community right out of high school, said Gayle Manchin, federal co-chair of the Appalachian Regional Commission, who is also the spouse of Sen. Joe Manchin. The federal-state partnership works to bring economic development projects and quality-of-life improvements to the people of Appalachia and specifically targets communities affected by coal's decline.

"The future of everything in that area was all based on the coal industry and it doing well," Gayle Manchin said. "When coal crashed, it was just a total devastation."

Losing access to bank branches complicates the process of rejuvenating a local economy bleeding jobs from a shrinking industry.

Community bankers sometimes utilize "soft" information, such as localized knowledge of a business opportunity or a borrower's character, when underwriting loans. Bank branch closings lead to a "persistent decline in local small business lending," according to a study by Hoai-Luu Nguyen, an economist at UC Berkeley. The researcher found that the effects can be highly localized, dissipating within 6 miles but affecting an area for up to six years.

Small community banks may also be more likely to engage in smaller business transactions than larger banks.

"We roll the dice on some people that some of the larger regionals probably don't pay a lot of attention to," Shupe said.

Pioneer wants to serve its core market and reinvest in those communities, but the lack of a replacement for the declining coal industry complicates those efforts, Shupe said.

"I'm not trying to bash our local politicians or even our state politicians, but I don't see a lot of thought going into what we can do to try to help these communities," Shupe said. "You've got to have something to entice someone to travel, to want to invest in a life there."

Banks will likely be taking a closer look at their branch networks and may need to make some difficult decisions, said West Virginia Bankers Association President and CEO Sally Cline.

"Their communities are so important to them," Cline said. "They sponsor soccer leagues and they're ingrained in our community. I think that bankers really have to examine their market losers and decide what to do with those offices."

The economic revitalization of coal-dependent communities will require more than new jobs. The region also needs to be a more appealing place to call home, Hille said.

Some of Mountain Association's work to make Appalachia a more desirable place to live includes fostering smaller-scale economic drivers. Small businesses such as coffee shops, walking trails or local bank branches may not employ as many people as a mining operation, but they can have an outsized impact. Without more cornerstones of social and economic life in the community, oft-touted worker training programs are likely to simply export valuable skills to other regions, Hille said, even if people do want to stay.

"It's an easy place to love," Hille said. "It's not always an easy place to live."