Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Sep, 2021

|

| Campaign billboards in Germany. Green momentum is pushing climate change up the agenda in the run-up to the Sept. 26 vote. Source: Sean Gallup/Staff/Getty Images News via Getty Images |

Voters in Germany, Europe's largest economy, go to the polls Sept. 26 for a federal election with climate change and energy policy as key battlegrounds.

Sixteen years of coalition governments led by Angela Merkel's Christian Democratic Union, or CDU, initially saw rapid build-outs of wind and solar power, but more recently have been characterized by a lack of progress on climate issues, just as other countries have made bold strides forward.

A rise in popularity of the country's Green Party is now forcing the larger parties to take a harder line on issues from Germany's coal exit to the rejuvenation of its fledgling onshore wind market, setting up what is billed as "a climate election" by German think tank Agora Energiewende.

As a sign of the times, the Green Party's candidate for chancellor, Annalena Baerbock, joined the CDU's Armin Laschet and Olaf Scholz of the Social Democratic Party, or SPD, for a series of televised debates, breaking tradition from the usual two-person format.

"The next government will be the last to have an active influence on the climate crisis, and I am deeply convinced that we can do it," Baerbock said during a Sept. 12 debate. "It is an enormous opportunity for our country."

But even against this backdrop, the next administration may fall short on delivering what is needed to decarbonize the economy and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C, as set out by the Paris Agreement on climate change.

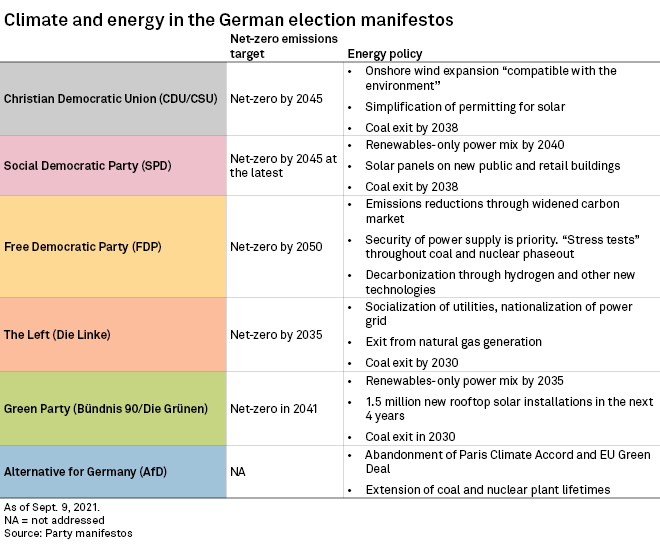

"None of the election manifestos are compatible with the 1.5-degrees target; the Greens are closest," Claudia Kemfert, head of the energy, transportation and environment department at the German Institute of Economic Research and a member of the German Environment Ministry's expert council on environmental issues, said in a Sept. 8 email.

New climate law 'still insufficient'

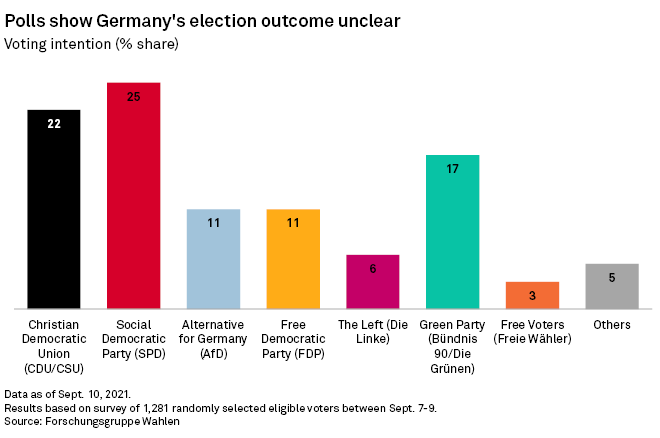

In Germany's political system of proportional representation, governments are usually formed through coalitions of two or more parties. The Green Party's polling results have catapulted the once small party to the club vying for the chancellorship and the party is likely, though not guaranteed, to form part of a new coalition government.

The Greens are putting pressure on other parties to take a stand on climate issues, while their possible role in a future government means other parties can defer to them for much of the policy detail, according to Karla Klasen, an associate at law firm Osborne Clarke in Cologne. "The Social Democrats and the Greens barely differ on climate and energy; the Greens go into the details and have thought things through, while the SPD is copying," Klasen said in a Sept. 8 interview.

The new government will inherit an overhaul of Germany's climate commitments, forced through in May after a court ruling, which moved the country's net-zero target forward to 2045 and introduced fresh milestones in the years until then.

While governing coalition partners, the CDU and SPD, as well as the Free Democratic Party are sticking largely to the newly defined climate objectives in their election manifestos, the Green Party has pledged to accelerate the decarbonization of Germany's economy, calling the revised climate law "still insufficient."

The Greens, the third-most popular party in voter polling, want to curb emissions by 70% by 2030, while also ushering in a faster coal exit, bringing it forward eight years from the existing 2038. By 2035, the party wants 100% renewable energy, which would help achieve net-zero emissions in 20 years, it said.

Kemfert said the new climate law is not compatible with the Paris climate accord and needs to be tightened further, and efforts should target net-zero emissions within 15 years. "To achieve the climate targets we need a massive renewables build-out, a coal exit by 2030 and a departure from fossil fuels in transport and buildings. This is extremely ambitious and can only succeed with a broad range of measures," Kemfert said.

Bureaucratic hurdles

In an Aug. 30 report, Agora laid out a set of recommendations for Germany's new leaders, including an annual €30 billion budget for climate-protection measures, starting in 2022.

It also recommends screening financing through the EU's sustainable finance taxonomy. Shutting down Germany's last coal-fired power plant can be achieved by 2030, the group argued, while onshore wind deployment needs to be tripled.

Growth of onshore wind has slowed in recent years amid a lack of suitable locations and growing local opposition. Agora called for further land to be made available and speedier permitting procedures, as well as for financial incentives for local communities.

In an analysis of election manifestos, German wind power association BWE found the Green Party has the strongest commitment to renewables and the deployment of new capacity, followed by the Left and then the ruling CDU and SPD. To reach Germany's net-zero target by 2045, BWE calls for annual onshore wind construction of 4.5 GW.

|

| Outgoing chancellor Angela Merkel. Source: Sean Gallup/Staff/Getty Images News via Getty Images |

"The big hurdle is the German bureaucracy," Daniel Breuer, energy lawyer and partner at Osborne Clarke, said in an interview.

The devolution of permitting responsibility to local authorities will remain a stumbling block for onshore wind regardless of high-level policy pledges, Breuer said. Meanwhile, solar is on a growth path, even outside of Germany's subsidy framework. "We are advising on a multitude of large utility-scale solar projects financed with [power purchase agreements]. Corporate demand is there because onshore wind isn't working," Breuer said.

Given the country's power needs and the pace of renewables deployment, Breuer does not consider a complete exit from coal by 2030 to be realistic. New gas power plants supplied by the incoming Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Russia could help accelerate the transition, he said.

Hydrogen pledges

Hydrogen plays a significant role in most parties' election pledges: The SPD wants to make Germany the leading market for hydrogen technology by 2030 and the Green Party pledges to collaborate with wind- and solar-rich nations for imports to top up domestic production.

The CDU said it will implement Germany's existing hydrogen strategy, which prioritizes green hydrogen, made from renewables with electrolysis, and targets 5 GW of electrolyzer capacity by 2030. The party will also accept blue hydrogen, made from natural gas with carbon capture, "in the transition phase."

Kemfert said it will take a decade before green hydrogen can be deployed at scale in Germany, exclusively in sectors where direct electrification is not possible.

"And in this decade we have to at least triple the rate of expansion of renewable energies and get out of fossil fuels," she said. "By choosing the wrong priorities, we create new fossil pathway dependencies, so that meeting the climate targets moves further into the future."