Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

30 Apr, 2021

By Michael O'Connor and Chris Hudgins

The potential for U.S. defaults remains low as companies take advantage of government stimulus and the economy continues to recover from the coronavirus crisis.

But as the economy recovers, more defaults could be on the horizon whenever the benefits of government aid wane and lenders become less lenient, experts said.

"There's going to be a day of reckoning," said Tim Weed, a partner at the professional services firm Plante Moran, in an interview.

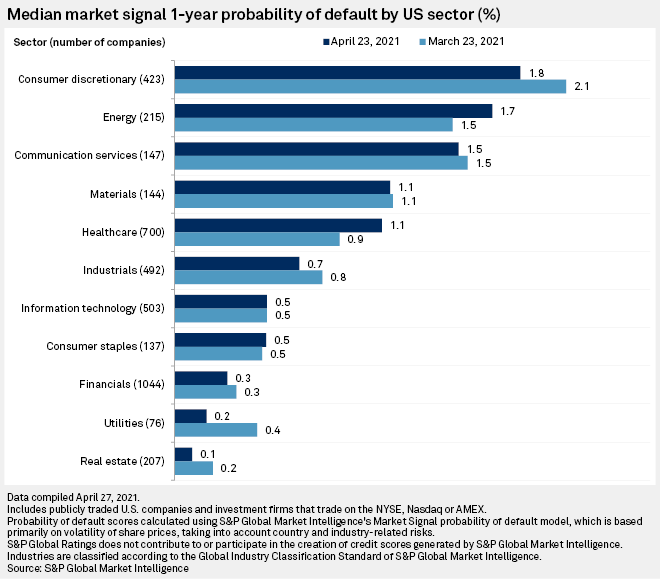

Median one-year probability of default scores fell across most sectors in April from a month earlier, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. The scores, which represent the odds of default within a year, are based primarily on the volatility of share prices for companies in the sector that trade on major U.S. stock exchanges and considers country and industry-related risks.

For the second month in a row, the consumer discretionary sector ranked highest among sectors, with a median probability of default of 1.8% as of April 23, down from 2.1% a month earlier. The score is based on 423 companies in industries such as restaurants and hotels, resorts and cruise lines.

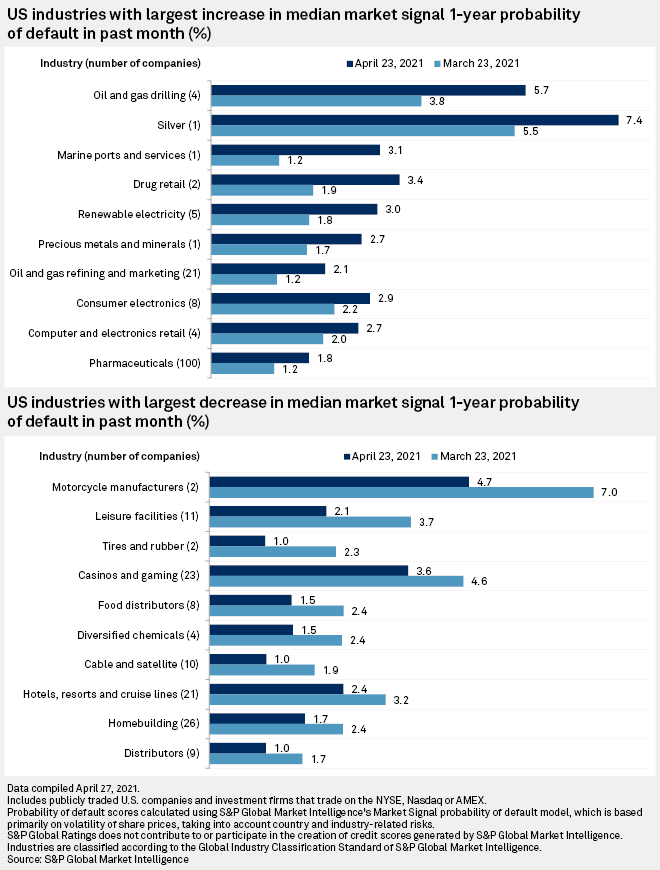

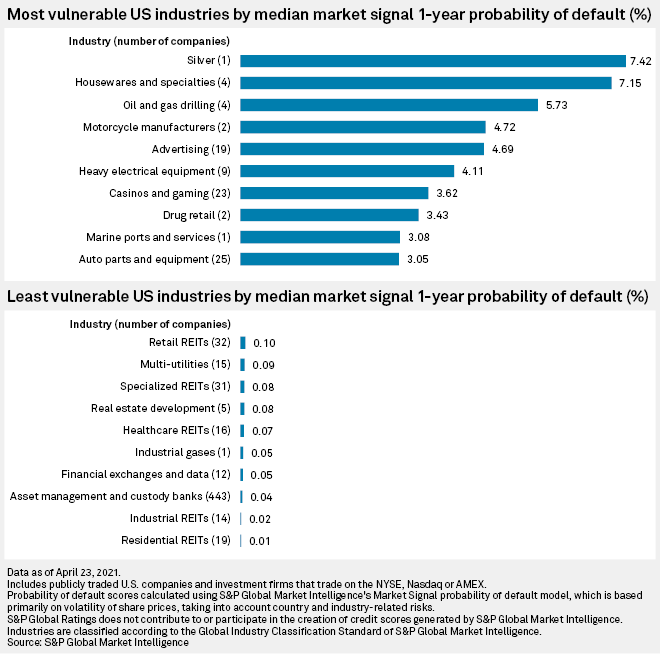

The energy sector ranked second-highest as of April 23, with a median probability of default score of 1.7%, based on 215 companies, a slight increase from 1.5% a month earlier. The healthcare sector's one-year median odds of default rose to 1.1%, based on 700 companies, from 0.9% in March. The median default odds rose during the month for energy companies in industries centered on oil, gas and renewable electricity, while pharmaceutical companies also logged an increase, according to Market Intelligence data.

The default odds remain well below the spikes during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S., and default prospects are expected to remain down as the economy recovers in tandem with the vaccine rollout in the U.S.

Ratings on March 30 lowered its estimate for the 2021 U.S. speculative-grade default rate to 5.5% from its 7% projection in February. The forecast applies to companies rated BB+ or lower and includes selective defaults. These companies can issue leveraged loans or bonds.

Buoyant share prices suggest that plenty of companies are benefiting from the current financial environment, while easier access to capital and government aid are helping businesses stave off defaults. The S&P 500 has returned 11.5% on the year as of April 27.

The pace of corporate defaults has been slower than expected, experts say. That could change for some industries like movie theaters and restaurants, however, as the economy resumes normal operations once the pandemic gets under control, according to experts.

"There's going to be some cleaning out of different parts of corporate America," Weed said. "We can paper over for a while, but eventually those things will come home to roost."

Twenty rated U.S. companies have defaulted so far in 2021 as of April 22, just more than half of the 40 defaults in the year-ago period, according to Ratings. Oil and gas companies lead that tally with four defaults year-to-date, followed by retailers and restaurants and media and entertainment companies, with three each.

Most of 2021's U.S. defaults were distressed debt restructurings, a process where a company strikes a new agreement to pay investors back either on new terms or for a reduced amount than what was originally borrowed. AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc., for example, on Jan. 15 exchanged $100 million of second-lien notes held by Mudrick Capital Management LP for common stock. Ratings considers the deal "tantamount to a default" because Mudrick received less than originally promised.

Lenders are refraining from enforcing technical defaults given the uncertainty created by the pandemic, but that is likely to change by the end of the summer as economic conditions normalize, said Connie Lahn, Barnes & Thornburg's Minneapolis office managing partner, in an interview.

Defaults are at record lows because stimulus packages enacted under the Trump and Biden administrations "have allowed companies to limp along that probably should have filed a long time ago," Lahn said.

"There's going to come a time when lenders start declaring defaults, when there's no more money to bail these companies out," Lahn said.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act and Paycheck Protection Program loans provided liquidity that helped companies manage the ongoing challenges of the pandemic, said Weed of Plante Moran. Companies and lenders are trying to work through challenges presented by the pandemic instead of resorting to defaults or bankruptcies.

"'This is unusual, and we're hoping to rock and get past it,'" Weed said of the general attitude between creditors and debtors.

The lack of defaults and the low number of bankruptcies has repeatedly defied expectations that broader pain was imminent in the market, suggesting a more gradual reckoning is in store, said Greg Segall, CEO of Versa Capital Management LLC, in an interview. Accommodative monetary and fiscal policy, flexible lenders and investors have staved off what should have been a higher number of defaults and bankruptcies, but harder to say is when such conditions will change, Segall said.

"I don't know why you're going to see the go-go markets turn around as long as they see the punch bowl is still out there from the standpoint of all the government support that's in place for the markets," Segall said.

There is nothing signaling an immediate change to the risk appetite for debt and equity that has helped keep default rates down, said David Meyer, co-head of Vinson & Elkins LLP's restructuring and reorganization practice, in an interview.

"As to how things proceed throughout the year, I think that is a little bit of an unknown," Meyer said.