S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

28 Oct, 2021

By Karin Rives and Camilla Naschert

| People bring water and food to neighbors in a Belgian town that suffered severe flooding in July 2021. Record rain tied to climate change killed at least 220 people in Europe this summer. Source: Tierry Monasse/Getty Images News via Getty Images |

To read all of our coverage of COP26, click here

When leaders from around the world gather in Glasgow, Scotland, on Oct. 31 for a pivotal climate summit, they will face a global crisis of unprecedented scope and magnitude.

Since nearly 200 nations came together for the landmark Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015, average global temperatures have risen another 0.3 degree C to reach more than 1.2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, data from NASA's Earth Observatory shows. This rapid warming trend has been accompanied by more extreme weather events that are affecting billions.

The journal Nature Climate Change recently reported that 85% of the world's population is now experiencing some form of climate change. Violent storms, crippling drought, flooding and other disasters have cost the U.S. alone $745 billion and more than 4,500 lives over the past five years, data from the NOAA Earth Systems show.

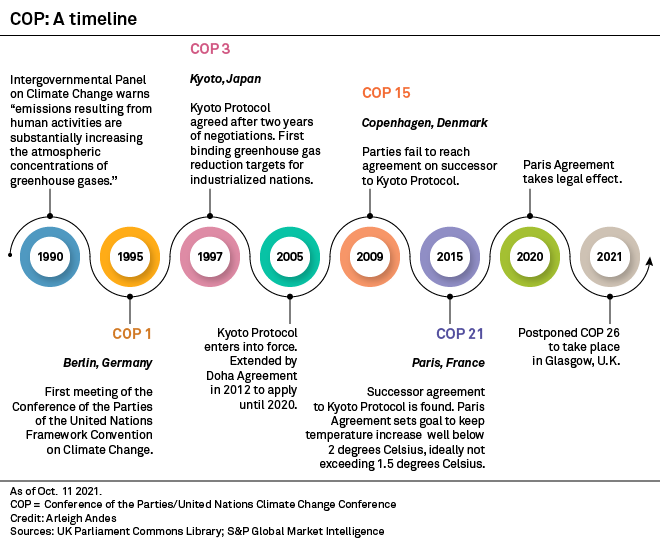

The world has been at work trying to slow climate change through the United Nations process for 26 years without bending the emissions curve in a meaningful way.

Glimmers of hope

Here is where things stand a few days before the critical climate summit, what is at stake, and what is expected.

Efforts to tackle the world's rapidly increasing greenhouse gas emissions picked up steam in the months leading up to the Glasgow summit, known as COP26. More countries are signaling they want action, even though details on deliverables and implementation are sparse.

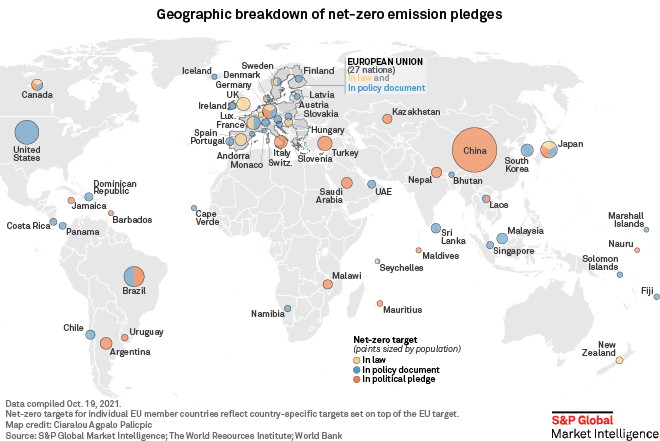

Shortly after taking office in January, President Joe Biden announced that the U.S. was rejoining the Paris Agreement and setting an economywide net-zero emissions target for 2050. China in September announced it would no longer fund coal plant construction abroad. The EU, Korea and Japan also committed to net-zero emissions.

"What happened over the past year in terms of target-setting is incredibly significant, more than I was expecting," said Lauri Myllyvirta, a lead analyst at the climate think tank Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

The rapid deployment and declining cost of wind, solar and other renewable energy sources since 2015 have also helped the world avoid “the absolute horror scenario” of a 5-6 degree warming, Myllyvirta estimated. With those market changes in the mix, he expects global emissions to peak sometime this decade.

READ: With COP26 on horizon, former UN climate chief draws hope from private sector

'Fate' of Paris treaty at stake

Still, COP26 President Alok Sharma in a flurry of appearances this year has been hammering home the message that the climate progress countries have made will not suffice.

In particular, Sharma hopes to lock in commitments that will keep global warming to 1.5 degrees, the more ambitious Paris target needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

"The world must honor the promises made here in Paris six years ago, and that ultimately rests with world leaders," Sharma told an Oct. 12 UNESCO press event in the French capital. "Success or failure of COP26 is in their hands and so is the fate of the Paris Agreement."

Gaps significant

A significant gap still exists between what nations say they will do and the reductions scientists say must occur. Pledged reductions and other commitments nations have not yet included in an NDC will only reduce emissions by 7.5% by 2030, far short of the 55% cut needed to meet the 1.5-degree goal, the U.N. said Oct. 26.

And should all nations just make good on their official pledges so far, the world would be headed down a "catastrophic pathway" toward 2.7 degrees by the end of the century, the U.N has warned.

For an expanded view of this map, please click here.

As concern over a potential failure at COP26 grows, U.N. officials have in recent days emphasized that countries are welcome to submit new and more ambitious NDCs at any time, including during the summit.

Large Western economies, with the exception of Australia, have already submitted their updated pledges. By contrast, China, the world's largest carbon emitter that in late 2020 said it will aim for net-zero emissions by 2060, has yet to update that goal. India, now the world's third-largest greenhouse gas emitter, has still to deliver a net-zero target. The same goes for Russia, which ranks sixth among emitters.

Meanwhile, oil-heavy Saudi Arabia announced Oct. 23 that it would reach net-zero by 2060. Like China, Saudi Arabia is aiming its net-zero goal for a decade beyond what is called for by the Paris accord.

And yet, some veteran climate negotiators like Kevin Conrad consider the COP talks critical.

"The Paris Agreement is the only option we have to solve this climate crisis," said Conrad, a negotiator for Papua New Guinea and the executive director of the Rainforest Coalition, a climate advocacy group representing more than 50 nations. "There is no plan B."

The four goals of COP26

The U.K. government, which is co-chairing COP26 together with Italy, has set four broad goals for the two-week climate conference held on a sprawling event campus on the banks of the River Clyde: firming up more ambitious emission reduction targets, increasing support for nations struggling to adapt to climate change disruptions, securing finance for developing nations, and what Sharma described as "working together to make the negotiations in Glasgow a success."

"COP26 is not a photo op nor a talking forum," he told UNESCO. "It must be the forum where we put the world on track to deliver on climate. Paris promised, Glasgow must deliver."

In Paris in 2015, developing nations most vulnerable to rising seas and failing ecosystems pushed to establish a goal to limit warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. The final text of the agreement called on nations to limit warming to "well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees, leaving the largest emitters with a lot of work to meet that goal.

Six years later and with less than a decade left to keep climate change manageable, the dynamics have changed. While the focus will remain on the largest polluters, there is now broad recognition that no country can afford to sit back.

"I think we're beyond this point of...common but differentiated responsibilities where the developed world has to go first," said Rachel Kyte, dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and a climate adviser to the U.N. and to COP26. "It's now in the self-interest of every country to reduce emissions as quickly as possible."

Climate finance: $100 billion and more

When it comes to finance, however, the ball remains in the rich countries' court. Sharma set as a top goal to secure the $100 billion in annual public and private finance that rich nations promised poor countries more than a decade ago.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development announced in September that developed nations mobilized nearly $80 billion in 2019 for funding efforts to address climate change in developing countries. That means they were still $20 billion short of their commitment.

Developing nations are expected to push rich nations to ramp up climate change funding through the end of the decade and to help with the losses and damages that are already occurring. Such financial commitments will add to investments rich countries must make themselves to shift away from fossil fuel.

"We need to effectively double [our] spending and investments in energy infrastructure for decades," Mark Carney, the U.N. special envoy of climate action and finance and former Bank of England governor, said Oct. 14. "We're talking an extra $2 [trillion]-$2.5 trillion of investment in [global] energy infrastructure alone. And that's before the spending on resilience, adaptation and hard-to-abate sectors, and other aspects. So these are big, big numbers – approaching 2% of global GDP."

How Glasgow can deliver

Negotiators at COP26 will be spending much of their time on nitty-gritty leftovers from previous climate summits, including rules for global carbon markets and other important details for implementing the Paris accord. That work comes after the two-day leaders' summit Nov. 1-2 where new announcements could be made from some of the largest emitters.

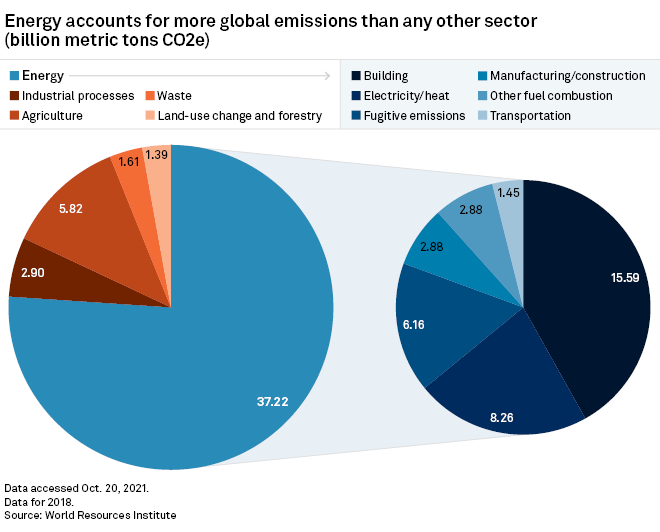

All eyes will be on the U.S., China, India and other G-20 economies, which are responsible for nearly 80% of global emissions. The U.S. has emitted nearly twice as much carbon as China since industrialization took off around 1750, but in recent years China has been catching up both with cumulative and annual emissions. India, a country with an expanding carbon footprint, comes in a distant third. Together, the three nations account for nearly 45% of global emissions.

When in Glasgow, President Biden is expected to tout regulatory and administrative steps he has taken to reduce U.S. emissions, along with efforts by U.S. cities and states. Tough negotiations in the U.S. Congress have been stripping away key components of Biden's climate plan, including the Clean Electricity Payment Program seen as critical for meeting the country's 2030 carbon reduction goal. But Democrats are now seeking to replace the program with grants, loans and energy tax credits to achieve reduction cuts from the power sector.

Theme

Location

Segment