Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

28 Oct, 2021

By Sanne Wass

To read all of our coverage of COP26, click here

The majority of banks' financed emissions may be excluded from their climate goals thanks to a loophole afforded to underwriting, raising concerns among shareholders and environmental organizations.

Some 87 banks globally have rushed to join the Net-Zero Banking Alliance ahead of the UN COP26 climate summit that starts Oct. 31, pledging to align their lending and investment portfolios with net-zero emissions by 2050. The alliance is meant to hold institutions accountable in their efforts toward reaching net-zero, with signatories committing to set targets for the most greenhouse gas-intensive sectors within their portfolios by 2030 or sooner.

Yet the guidelines only mandate banks to set targets for on-balance sheet investment and lending, while for off-balance sheet activity such as underwriting, it is optional. This allows banks to ignore a substantial portion of their fossil fuel financing in their policies, which non-governmental organization Reclaim Finance has described as being "as meaningless as a football match without a second half."

"Most people have no idea what underwriting is," said Paddy McCully, a senior energy transition analyst at Reclaim Finance, in an interview. "So if a bank policy covers lending, they think the job is done."

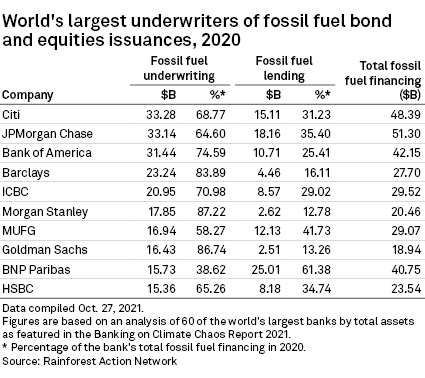

Underwriting refers to the financing that banks facilitate for companies by issuing bonds or shares on their behalf and selling them to investors. In 2020, 60 of the world's largest commercial and investment banks provided $750.73 billion to the fossil fuel industry, 65% of which through the underwriting of bond and equity issuances, according to figures from the Rainforest Action Network, an environmental organization.

Citigroup Inc. last year was the bank that underwrote the most fossil fuel debt and equities issuances globally, at $33.28 billion, corresponding to 68.8% of its total financing for fossil fuel companies, according to the data by Rainforest Action Network. It was followed closely by JPMorgan Chase & Co., which underwrote $33.14 billion and Bank of America Corp., which underwrote $31.14 billion, in the same period, comprising 64.6% and 74.6%, respectively, of their fossil fuel financing.

JPMorgan and Bank of America declined to comment, while Citi did not respond at the time of publication.

There has been "a big acceleration" in banks adopting new fossil fuel strategies since the Paris Climate Agreement in late 2015, starting with policies on coal and now increasingly on oil and gas, according to McCully. But the analyst noted they are almost all lending policies.

Barclays PLC and JPMorgan appear to be the only of the world's largest banks so far to have set interim sectoral targets that include underwriting activity, according to ShareAction, a nonprofit that coordinates investor campaigns.

By excluding important non-balance sheet items such as capital markets underwriting and the undrawn portion of loans, banks may be greatly underestimating their activities and transition risk, according to a report by ShareAction released earlier this year. Banks that do not make efforts to reduce their exposure through this part of their portfolio will be particularly vulnerable to potential government legislation impacting fossil fuel supply and demand, said Jeanne Martin, a senior campaign manager in the organization's banking standards team, in an interview.

'Great first step'

Insisting that signatories to the Net-Zero Banking Alliance include off-balance sheet emissions from the outset could have delayed actions in other areas, said Sarah Kemmitt, lead for the Net-Zero Banking Alliance at the UN Environment Programme. Kemmitt defended the current design as "immediately practical and actionable" and a "real great first step."

"We know that the banks can immediately get started with their on-balance sheet lending and investment, and the methodologies are mostly there. The data is improving," the lead said in an interview.

The Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials, or PCAF, for one, provides a framework for banks to assess and disclose greenhouse gas emissions of loans and investments, and already has close to 170 financial institution members.

A lack of common methodology that enables comparability between lenders is one key issue holding banks back from implementing off-balance sheet emissions in their targets, said Bridget Beals, co-head of climate risk and decarbonization strategy at KPMG, who works with lenders on their net-zero policies. Banks risk adopting one framework today, only to have to make material adjustments a year later, Beals added.

PCAF is working with a group of large investment banks to harmonize the measurement of capital markets underwriting, which it refers to as "facilitated emissions" rather than "financed emissions," said Giel Linthorst, executive director at PCAF. The working group aims to publish a method by the summer of 2022, and finalize it toward the end of the year after a consultation process.

While the remit of PCAF is to help banks measure and report the emissions, how to build that into targets and policies will be up to banks themselves and groups like the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, Linthorst said.

Not straightforward

Banks face a range of challenges in agreeing on such standards, including how underwriting activity is captured, according to Linthorst. Institutions measure their on-balance sheet emissions at a certain point in time, but this doesn't lend itself well to measuring underwriting activity, which is short-term in nature and can fluctuate significantly, the executive said.

Another debate in the working group is about how large a share of emissions should be attributed to a bank as a facilitator, Linthorst said.

Barclays has addressed this by only accounting for one-third of the emissions it underwrites, saying that it acknowledges its role in financing emissions but has no residual exposure to the equity and debt securities.

Speaking at the Sibos conference on Oct. 12, Abyd Karmali, managing director for environmental, social and governance client advisory at Bank of America, argued that by including off-balance sheet emissions in their measurements, banks might be getting into double attribution of emissions for both clients and the bank.

Pressure from investors

While PCAF discussions are progressing, the Net-Zero Banking Alliance has said it will consider off-balance sheet activities in the next version of the guidelines, which are due in April 2024.

Shareholders expect banks to act faster than that, said Martin of ShareAction. In a July letter to 63 banks, 115 investors representing $4.2 trillion asked lenders to go beyond the pledges made through the Net-Zero Banking Alliance by publishing short-term targets on all relevant financial services ahead of 2022 annual general meetings. Currently, signatories to the Net-Zero Banking Alliance have 18 months after joining to set their 2030 targets.

Barclays and JPMorgan have shown that it is possible for banks to introduce their own methodologies for measuring emissions facilitated through underwriting, Martin said. Barclays first launched BlueTrack in November 2020, a methodology that "is far from perfect, but they've done it," the campaign manager added. "And in addition to that, they did it quite rapidly."

Theme

Segment