Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

9 Feb, 2021

By Yannic Rack

| Rampion offshore wind farm in the U.K. is one of the projects supported by the original Green Investment Bank. |

As the U.K. government plots how to achieve its net-zero emissions target, ministers are preparing to launch plans for a new national infrastructure bank to drive money into low-carbon sectors — once again putting the spotlight on the country's former state-owned Green Investment Bank and its controversial sale to Macquarie Group Ltd.

Set up in 2012, the Green Investment Bank, or GIB, was a key early backer of the U.K.'s offshore wind industry and also helped draw private money into a range of other ventures, from biomass and waste-fired power plants to energy efficiency projects. But the government decided to sell the GIB to Macquarie, the Australian financial giant, for £2.3 billion in 2017 to reduce public debt, kicking up a flurry of criticism over abandoning the bank's green mission.

Now known as Green Investment Group Ltd., or GIG, it has since morphed into one of Macquarie's main investment brands and one of the largest dedicated renewables infrastructure investors in the world, reaching far beyond the U.K.'s borders.

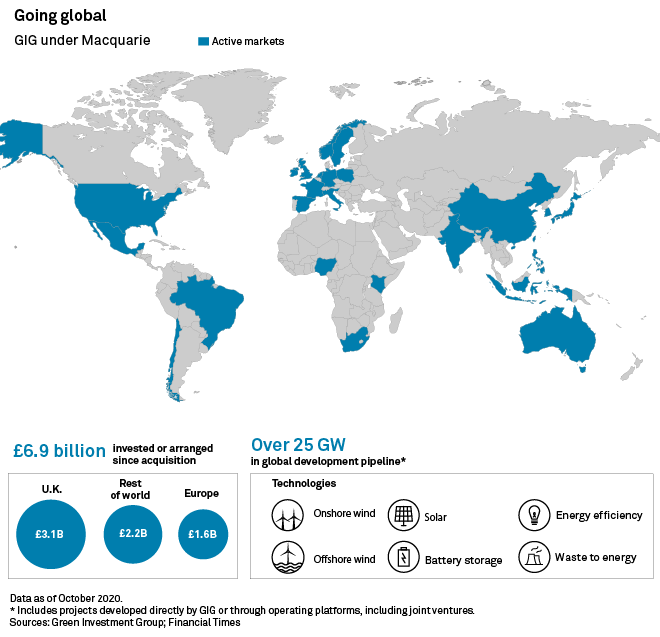

In the three years since it started operating under Macquarie, GIG has invested and arranged a total of £6.9 billion and expanded its activities to at least 26 countries around the globe, including the U.S. and large parts of Asia.

That has confirmed the fears of many environmental advocates, who after privatization wanted the bank to remain focused on the U.K. About £3 billion, or less than half of GIG's investment volume since the sale, was spent in the U.K., with the rest invested in mainland Europe and elsewhere.

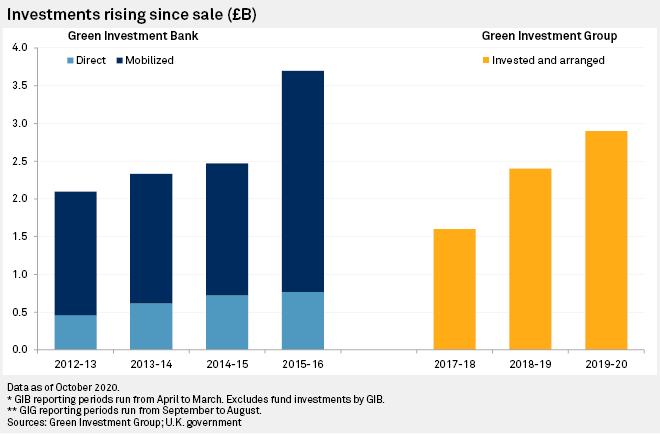

By comparison, the old bank had directly invested about £2.8 billion and mobilized an additional £8.2 billion between 2012 and 2016, according to annual accounts published by the government. It also made some smaller investments through third-party funds and, over its full four-and-a-half-year lifespan, committed a total of £3.4 billion.

GIG, for its part, has more than fulfilled a pledge made at the time of the sale to invest at least £3 billion in the U.K. and Europe during its first three years. But critics say far more could have been achieved by keeping the bank public, since Macquarie naturally pursued a more commercial strategy. GIG declined a request for an interview.

"Macquarie and GIG have done exactly what we expected them to do," said Nick Mabey, chief executive of E3G, the environmental think tank that developed the idea for the GIB. "We were concerned that they would pivot to investing in easy-to-finance, highly profitable projects around the world in the renewable space, which is what they've done."

Since the sale, GIG has entered offshore wind markets in Taiwan and Korea, invested in large onshore wind parks in the Nordics and developed solar plants in the U.S. It still finances waste-fired power plants and has launched a handful of energy efficiency offerings, including through a £200 million joint venture with the U.K. government that invests in India and sub-Saharan Africa.

"It didn't do bad things, but it didn't do the things we needed them to do," Mabey said.

To be sure, GIG still puts money into European markets. This month, it launched a subsidiary to pool its activities in utility-scale solar and integrated storage in the region, pointing to a development pipeline of more than 8 GW across 150 projects. And in December 2020, the company said it will put money into a project to explore both carbon capture and the production and distribution of hydrogen at an English port.

Still, critics say that compares poorly to what the GIB could have done — specifically in launching new markets for less established technologies and solutions beyond renewable power generation.

"The whole purpose behind the institution changed and we lost the critical mass," said Vince Cable, the former leader of the U.K.'s Liberal Democrat party, who set up the bank as secretary of state for business in 2012 and strongly opposed the sale. "I thought then and think now that it was a bad move," he said.

By the time of its sale, the bank faced rising criticism that it had become complacent, sticking around in sectors after they had matured and directly competing with private investors, particularly in bids for new offshore wind projects.

Some market observers also point out that private investors have continued to put money in green infrastructure in the U.K. and warn that any new government-backed bank needs to have a clearly defined remit. Otherwise, they fear the new bank could once again compete in established markets, rather than building new ones.

"I can see that there is a need for an institution like it. But it's vital that its mandate remains focused on genuine market failures," said Richard Nourse, founder of London-based Greencoat Capital LLP, one of the largest clean energy fund managers in Europe.

To assuage concerns that the bank may lose its green focus after the sale, a board of trustees was put in place to keep tabs on Macquarie's activities and ensure it continues to function as a market leader, rather than "one of many mainstream players on an increasingly crowded pitch," as the trustees put it in their latest annual report.

While the board praised GIG's continuing investment in the U.K. and its increasing role as a development partner, rather than a late-stage financier, it criticized the group's failure to move into some of the other areas it initially said it would target, such as energy storage, bioenergy and tidal energy.

A report by the U.K.'s National Audit Office completed after the sale in 2017 noted that, while the GIB had been set up on a sound basis, the government lacked evidence to show that it had achieved its green impact, especially outside of the offshore wind sector.

The British parliament's public accounts committee put the issue in starker terms in early 2018, saying the bank "failed to live up to original ambitions and now there is no guarantee that it ever will because its green intentions are not sufficiently protected" in the sale.

"We believe that it was a misjudgment that the [the U.K. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy] has so little assurance over GIG's future investment in the U.K. and in emerging technologies, which will be crucial to ensuring that the U.K.'s green commitments are met," the committee said.

A new start

The government has said it wants to soon set out a detailed proposal for a new iteration of the bank, the so-called National Infrastructure Bank, which could start operations on an interim basis as early as this spring. The new bank should also replace some of the funding formerly provided by the European Investment Bank, which has withdrawn from the U.K. as a result of Brexit, at least for the time being.

The EIB used to spend billions in the country, providing more green energy funding than even the U.K.'s own green investment bank. Without its funds, an analysis from the London School of Economics already predicted in 2017 that the U.K. would see "a net loss in low-carbon investment."

Mabey and Cable think there are plenty of markets the new bank could play a role in, including hydrogen and other sustainable transport sectors, supply chains in the battery industry and even nature-based solutions. Mabey said the new bank could also take a stronger role internationally, promoting the U.K.'s green priorities abroad, and emphasized that it should be run in strong cooperation with regional and local authorities in Britain.

Still, "we've lost very precious years," Mabey said. "We could have had a whole infrastructure for funding set up [for these technologies]."

The new bank could also have more firepower, which some argue is desperately needed. The Committee on Climate Change, which advises the government, estimates that that extra investment needed to achieve net zero will grow from about £10 billion per year in 2020 to about £50 billion in 2030.

The old bank supported about 100 projects throughout its lifespan, but had been limited both by EU state aid rules and its inability to raise money on the private market. If the latter restriction is removed, the new bank could do a lot more, said Cable — even though he estimates it would take two years to get it fully up and running.

"It's very much a second best to having the Green Investment Bank continuing," he said. "But if it can't be brought back, they will just have to start again."