S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

8 Feb, 2021

Trillions of dollars of stimulus are ready to be pumped back into the global economy, but by households rather than governments or central banks.

Developed economies have been hit particularly hard by the coronavirus pandemic partially because they are so dependent on consumer spending. S&P Global Ratings economists forecast that 2020 GDP in the U.S., eurozone, Japan and U.K. shrank by 3.9%, 7.2%, 5.5% and 11% respectively.

But elevated household savings rates and accelerating vaccination programs suggest a deluge of spending power that was stored up during the pandemic in those economies will be unleashed in 2021 and 2022.

"China and Asia are leading the recovery but they're really leading it on the supply side," Paul Gruenwald, global chief economist at S&P Global Ratings, said in an interview. "Consumer spending has been relatively weak, and the labor market is soft. They're exporting to the rest of the world and piggy-backing on the demand of that recovery. If this all plays out, we get a stronger recovery in countries which have a bigger chunk of consumption in the basket."

S&P Global Ratings expects U.S. growth to rebound by 4.2% in 2021, with GDP recovering to the size it was at the end of 2019 by the third quarter of this year, depending on the size of fiscal stimulus from the Biden administration.

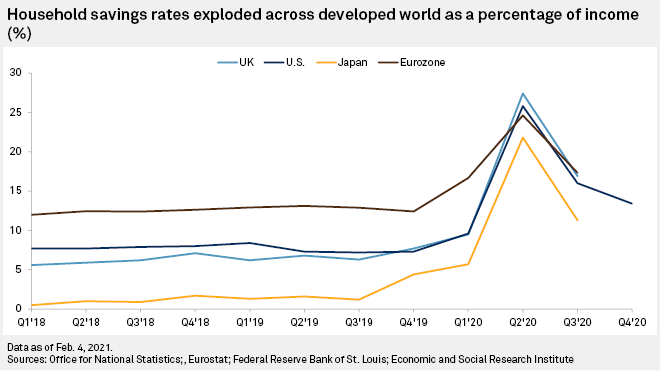

Much of the momentum will come from household savings that surged to 25.8% of income in the second quarter of 2020, having been just 7.3% at the end of 2019. While the rate fell to 16.0% in the third quarter as the economy partially reopened, it was still well above pre-pandemic levels.

|

The U.K. quarterly saving rate surged to 27.4% in the second quarter of 2020 having been 7.7% before the crisis, while the eurozone saw the rate climb to 24.6% from 12.4% and Japan to 21.8% from 4.4%.

Consultancy Oxford Economics calculates that over the course of the crisis, U.S. households saved $1.6 trillion more than they would have done. HSBC estimates that households in the eurozone and U.K. saved €470 billion (3.9% of GDP) and £170 billion (7.7% of GDP) more in 2020 than they did in 2019, setting up each region for a major spending boom once the virus is suppressed.

Economic disparity

History would suggest that savings rates can quickly fall back to pre-crisis levels, though the speed of this particular recovery will depend on how soon governments can suppress the virus and how much economic scarring there will be to weigh on consumer confidence.

"Before the great financial crisis there was too much household borrowing, [in the aftermath] they had to strengthen their balance sheets. This time it was a health led crisis so eventually savings rates will go back to where they were," Gruenwald said, noting, "we're not working off some huge imbalance like we were heading into the financial crisis."

The distribution of the savings is one obstacle for a consumption boom, with better-off households making up the bulk of the extra savings, whereas poorer households have seen theirs decline.

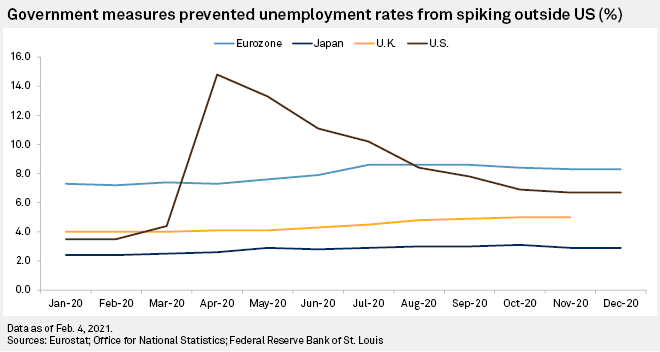

Oxford Economics estimates that the top two income quintiles in the U.S. own all of the $1.6 trillion of extra savings. By contrast, the bottom three quintiles have been squeezed during the crisis, which saw the rate of unemployment surge from 3.5% in February 2020 to a peak of 14.8% in April before steadily falling back and sitting at 6.7% in December.

However, the consultancy expects the government's eventual stimulus package to provide $1 trillion to household disposable income, with unemployment benefits and another round of checks bolstering the spending power of lower-income families.

"Lower- to middle-income families should be able to spend more freely on the back of generous fiscal transfers under [U.S. President] Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan, while higher-income families should benefit from big 'cash stashes' and steady pay," Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics, wrote in a research note.

Japan employed similar measures early in the crisis, boosting disposable income with ¥100,000 stimulus payments to every man, woman and child in the country. Consultancy Capital Economics suggested that without these payments, the household savings rate would have only risen to 11.6% in the second quarter rather than 21.8%.

However, furlough schemes also protected employers and the unemployment rate has been relatively stable, at 2.9% in December 2020, up from 2.4% a year earlier.

"We do expect the household saving rate to fall sharply over the coming quarters as the economy reopens and those stimulus payments are no longer paid," Marcel Thieliant, senior Japan, Australia and New Zealand economist at Capital Economics, wrote in an email.

Job support

In the eurozone and U.K. the upticks in unemployment have also been mild — up to 8.3% from 7.2% pre-crisis, and to 5% from 4%, respectively — as governments opted for furlough schemes to shift the burden of paying salaries away from companies and onto the government's balance sheet.

"[In] those economies which have had extensive job support schemes, job losses have been limited — and those on furlough can come back to work quickly — and the incomes of those people who have been furloughed has held up fairly well," Chris Hare, senior European economist at HSBC Global Research, wrote in an email. "My sense is that these economies may be better placed to bounce back, as they may suffer less scarring from long-term unemployment."

HSBC expects the savings rate in the eurozone to return to 13.8% by the end of 2022 — still higher than the 2019 average of 12.8% — with the U.K. forecast to have wound its savings rate down to 7.2%, versus a 2019 average of 6.5%.

Vaccination programs

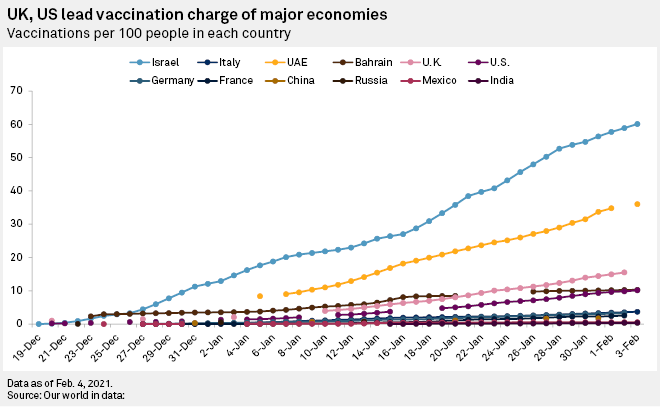

The speed at which those savings will be converted into expenditure will partly depend on the pace of the vaccination programs and partly on scarring, both economic and psychological.

While Israel and the UAE are leading the global charge, having given 57.5 and 36.5 vaccinations per hundred people respectively as of Feb. 4, the U.K. and U.S. are leading the way for the developed economies, at 16.5 and 10.3, respectively, according to the Our World in Data project at the University of Oxford.

In the eurozone the pace is much slower, stymied by production problems and the European Commission taking longer to procure vaccines. The rate in Germany and France, the two largest economies in the bloc, was just 3.4 and 2.7, respectively.

But the successful rollout of the vaccines will only be one aspect of getting people to spend their savings.

"The sufficient condition which also needs to happen is the behavior of individuals. People need to get comfortable with the idea of going to restaurants, going to events as groups," Gruenwald said, noting, "it's going to be a combination of rollout and loosening of restrictions, and then people will start spending again."