S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

25 Jun, 2021

By Karin Rives

| NRG Energy shut down its Petra Nova carbon capture project in 2020 when oil prices plummeted. |

Carbon capture at aging U.S. coal plants has always been a long shot financially, and the outlook for such projects appears to be dimming as private investors look elsewhere and federal support for the technology wanes under the Biden administration.

None of the five proposals to retrofit coal plants with carbon capture technology in the U.S. has secured funding to construct the scrubbers, carbon absorbers and geologic storage sites needed to begin operating. Some analysts also warn that costs could escalate, ultimately leaving ratepayers and taxpayers responsible for runaway expenses should projects be abandoned.

The $1.4 billion carbon sequestration and storage facility planned for the 847-MW San Juan Generating Station in New Mexico, for example, is nearly two years behind schedule. Enchant Energy, the company championing the project, now says it will need a $906 million loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Energy and another $90 million in debt financing from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Rural Utilities Services program to continue development.

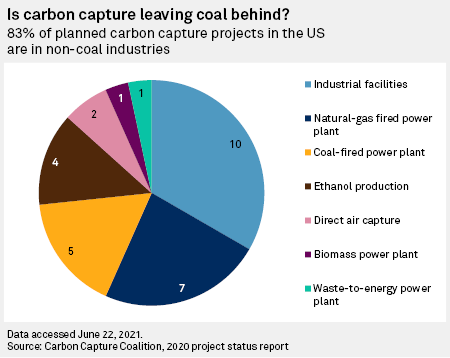

Whether such public financing will materialize is uncertain. The DOE under President Biden is shifting carbon capture research and development spending away from coal plants and toward relatively new natural gas-fired power plants and hard-to-abate industry sectors such as cement manufacturing.

"As you know, this office has invested a great deal of time and resources in cleaner coal," Jennifer Wilcox, the DOE's principal deputy assistant secretary for fossil energy, said April 30 during an event hosted by the Carbon Utilization Research Council. "But it’s fairly clear that carbon capture may not make economic sense on the remaining existing fleet of coal-fired power plants in the U.S. — plants that are mostly based off of subcritical efficiency boilers and nearing retirement over the next decade."

Meanwhile, private funding for costly carbon capture projects is drying up as banks and equity firms adopt policies discouraging coal investments.

A plant with no transmission lines

Financing aside, the San Juan project faces significant practical hurdles. The transfer of the plant from its current utility owners to the City of Farmington and on to Enchant remains in limbo after two years of unsuccessful negotiations, said Ray Sandoval, a spokesman for the plant's majority owner Public Service Co. of New Mexico, or PNM.

Unless Enchant can show that its carbon capture project is economically viable and that it can shoulder $29 million in future mine and plant decommissioning costs, the San Juan coal-fired plant will shut down as planned in June 2022 when PNM and the other owners exit, Sandoval said.

Enchant CEO Cindy Crane insisted in an email that such details will be worked out and that San Juan will run without the carbon capture technology through 2024. The City of Farmington said it will assume full ownership of the plant a year from now at a cost of $1 before transferring it to Enchant.

"There have been many delays in 2020 and early 2021 … caused by COVID-19 that have slowed the on-the-ground work and the due diligence necessary for additional investment," Crane said. "We are confident that we will be able to secure the additional development capital needed."

But even if the ownership transfers go through, the San Juan plant will no longer have immediate access to PNM's transmission lines a year from now. The utility retains the rights to that infrastructure, and Sandoval indicated that PNM needs the capacity on those lines to transmit power to its customers in New Mexico urban areas from the solar farms that will replace the output of the San Juan plant.

"They say they will operate without carbon capture, but what transmission are they going to use?" Sandoval said. "It's like we’re living in a twilight zone."

Supporters undeterred

Meanwhile, North Dakota's Minnkota Power Cooperative Inc. is conducting an engineering study for what it promises will be the world's largest carbon capture facility, dubbed Project Tundra, at the 692-MW Milton R. Young power plant. The project received $43 million in initial DOE grants under former President Donald Trump.

Carbon capture projects at two other coal-fired plants, the 1,630-MW Prairie State Energy Campus plant in Illinois and the 1,365-MW Gerald Gentleman plant owned by the Nebraska Public Power District, also received millions of dollars in initial R&D grants from the DOE in 2019.

Similarly, a plan for a massive geologic carbon storage complex in Mississippi, led by the Southern States Energy Board, is being supported by the $28 million in DOE grants disbursed thus far.

The projects are bolstered by state leaders and members of Congress seeking to keep fossil fuel plants running and to secure coal sector jobs. However, neither the Project Tundra developers nor any of the other developers have made final decisions on whether to move forward with their projects, much less secured funding to break ground.

Some industry figures are blunt about the idea of retrofitting coal plants that may be a decade or two from retirement.

“Carbon capture really is irrelevant for our existing coal fleet," Jeffrey Lyash, president and CEO of the Tennessee Valley Authority, said June 16 during the American Nuclear Society's annual meeting. "Backfitting the technology to that old asset is not going to be cost-effective under any scenario.”

Such views contradict arguments from carbon capture supporters, who say coal plants must keep operating to maintain a reliable grid and jobs in fossil-heavy states. America's handful of developers also remain undeterred.

Minnkota applied for a carbon storage permit with the North Dakota Department of Environmental Quality in late May. If that permit is approved, the rural power cooperative must seek a Class IV well permit under the federal Clean Water Act. So far, the timeline for starting construction at the 51-year-old Milton plant in 2022 remains intact, said Stacey Dahl, Minnkota Power's senior manager for external affairs.

Stuck with the bill

In Mississippi's Kemper County, the project team for the ambitious ECO2S underground carbon storage complex continues to explore the area's geology to determine if it can store up to 438 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. The captured carbon would be piped in from natural gas and coal plants in Mississippi and Alabama; the total cost of the storage project and the various plant retrofits has not yet been determined.

Kemper County was also home to Southern Co.'s ill-fated coal gasification and carbon capture venture, which Mississippi regulators called off in 2017 to protect ratepayers against $6.4 billion in losses. The DOE contributed $387 million to that project.

Whether the regional carbon storage project progresses will depend on whether the DOE issues additional grants under its CarbonSAFE program, Ben Wernette, the Southern States Energy Board's staff geologist, told Market Intelligence. Construction would be funded using a "combination of federal and industry dollars," he said.

Critics warn that federal and state taxpayers as well as ratepayers may ultimately pay for carbon capture projects that prove unsuccessful. Such concerns have grown louder since NRG Energy Inc. suspended operations at the nation's only operating coal-fired plant carbon capture facility, Petra Nova in Texas, last year.

NRG said that low oil prices eliminated the market for using captured carbon to flush out oil from nearly depleted production fields. But the company's own data showed that the $1 billion Petra Nova facility had not managed to operate as effectively as planned. The DOE gave $190 million in grants to the project.

Minnkota estimates its North Dakota project will also cost $1 billion, but that is "optimistic" considering Petra Nova was half as large and could never run at full capacity, cautioned the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, or IEEFA, a group critical of carbon capture projects.

Customers of the two cooperatives that purchase electricity from the Milton R. Young plant already pay more than they would if the power came from the wholesale market, said David Schlissel, IEEFA's director of resource planning analysis.

"Adding carbon capture to the plant is only going to raise its costs," Schlissel said, "and ratepayers and customers are likely to end up stuck with the bill for the whole risky venture."