S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

25 Jan, 2021

By Aries Poon, Rebecca Isjwara, and Mohammad Abbas Taqi

Despite rising global systemic risk scores of Chinese megabanks, their predominantly domestic footprint and the limited overseas use of the yuan suggest a low likelihood of them triggering a Lehman-like global financial crisis in an event of a bank failure, experts say.

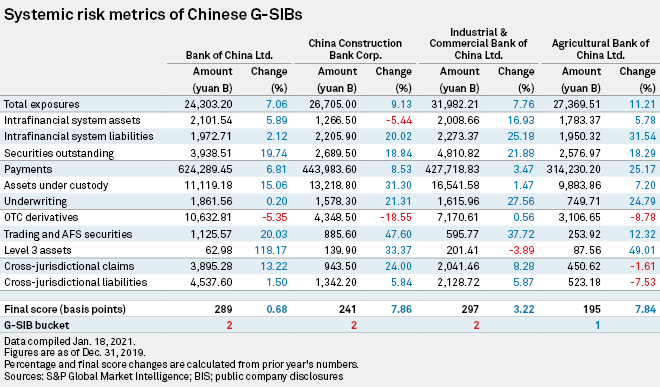

Among 30 global systemically important banks, or G-SIBs, China Construction Bank Corp. was the only institution that moved to a higher bucket in the latest annual assessment by the Financial Stability Board based on end-2019 data. The total G-SIB score of Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd., the world's largest bank by assets, rose for the fifth consecutive year, Agricultural Bank of China Ltd.'s score rose for the third straight year, while Bank of China Ltd.'s score was largely flat after rising for four years, according to the FSB and S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The assessment comes as a spate of prominent Chinese state-backed companies defaulted on their bonds, the average nonperforming loan ratio of the nation's commercial banks rose to a multiyear high, and Beijing announced measures to rein in the financial risks of shadow banks, microlenders and third-party payments platforms that was believed to be a reason behind the abrupt halt of Ant Group Co. Ltd.'s massive IPO.

"Frankly speaking, the linkage between the global financial system and Chinese banks is still relatively limited," Hang Qian, a partner at Oliver Wyman, told S&P Global Market Intelligence. "It's much more meaningful to look at, given the size, how assets on their balance sheet are spread across [jurisdictions]."

Much of the gains of Chinese banks' G-SIB scores were due to their large size, one of the five elements of the formula. The scores of other elements, such as complexity, cross-jurisdictional activity and non-substitutability, which indicate the difficulties of coordinating resolution and the spillover effects from any failure, were still markedly lower than many other G-SIBs of similar ranks from the U.S., Europe and Japan.

Mostly domestic growth

Chinese lenders have been expanding their balance sheets as they heeded the government's call to lend more to power the nation's economy, which showed signs of slowing before the COVID-19 pandemic. As of end-2019, total assets of the Chinese G-SIBs rose by between 7.1% and 10% from a year ago, according to the banks' annual reports.

The scores reflect "the trend that the size of Chinese banks have continued to grow rapidly together with [China's] large economic size relative to the world," said Gary Ng, an economist of Asia sectoral research at Natixis. China's economy grew 6.0% in 2019, higher than the global economy's 2.4% growth, according to the World Bank.

As China becomes one of the world's largest manufacturers, consumers and trading partners, as well as a major funding source for many less-developed countries under the nation's so-called belt-and-road diplomatic initiative, Chinese megabanks have also been expanding abroad more quickly over the last decade than before.

Still, much of their asset growth remains domestic due to Beijing's directive to prioritize the nation's own growth. At the end of 2019, China Construction Bank, Bank of China and Agricultural Bank of China said less than 10% of their total assets were located outside mainland China, while ICBC said about 13% of its total assets were offshore, according to their annual reports.

"If you look at the balance sheet of these Chinese banks, even though they are big, and that's why they have the systemically important bank status, their global connections are limited," Qian said. "If you look at the U.S. banks that are systemically important, their assets are cutting across multiple jurisdictions … and are still much more systemically important than Chinese banks."

Limited offshore use of yuan

The use of the yuan outside mainland China is still limited, partly due to the country's capital controls, which will somewhat cushion the spillover effect on the global financial system should a Chinese G-SIB fail.

As of end-2019, the yuan accounted for 1.8% of global foreign exchange reserve assets, according to the International Monetary Fund's data. Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar accounted for 57%, the euro 19%, the Japanese yen 5.5% and the British pound 4.3%.

"When the Chinese currency becomes one of the major settlement currencies in the world, almost on par with the U.S. dollar … that's the point when the global economy needs to be much more mindful of that," Qian said.

In 2016, the yuan joined the U.S. dollar, the euro, the yen and pound in the IMF's special drawing rights basket, which determines currencies that countries can receive as part of IMF loans. While the move was seen as a milestone for China's efforts to internationalize the yuan, it remains debatable whether the yuan has fully met IMF's reserve currency criteria of being "freely usable," in which the fund defines the currency "has to be widely used to make payments for international transactions and widely traded in the principal exchange markets."

Multiple domestic buffers

Experts also believe Beijing's tight grip over its financial system, from banking regulations and market liquidity to the exchange rate, is likely to minimize the chance of having a major bank failure in the first place.

"China is now more mindful about excessive stimulus causing a rapid build-up of leverage and financial risks; yet, we think China will take a slower approach to of tapering monetary conditions towards normalization policies, while keeping an accommodative policy stance to facilitate the private sector's recovery," said Bruce Pang, Head of Macro and Strategy Research at China Renaissance Securities (Hong Kong).

The country's long-awaited plan to identify up to 30 domestic systemically important banks, or D-SIBs, was also kicked off early this year, although the authorities have not announced the additional capital and leverage requirements for different buckets.

"The measures will certainly help reduce the possibility of Chinese banks incurring material and systemic risks," said Yongmei Cai, a partner at Simmons & Simmons Beijing.

Risks are still there

Despite a low probability of contagion, China's gradual opening of its market to foreign investors in recent years remains a potential risk, albeit limited, to the global financial system, experts say.

"We think the potential domestic risks facing Chinese banks, such as earning pressure, bad debt and asset quality amid economic slowdown and implemented reforms, may cause some risks and greater disruption to the wider financial system and global economic activity," said China Renaissance's Pang. But he added "we see no near-term disruptions and risks from Chinese banks on global stability."

Natixis's Ng added that foreign ownership of Chinese bonds and equities has risen in recent years as Beijing allows them more access, which is another potential risk to the world's markets.

"As long as the sovereign yield is not impacted, the spillover to the world through bond yields and the [yuan] should be manageable and the market would perceive the risks are contained in specific firms, which mean the fear should be limited," he said.

These risks, if mismanaged, could still send tremors across the world, but probably through a broader consumption slowdown or supply-chain disruptions, experts add.

"Hypothetically, assume there's a financial crisis in China, which I have to say is very unlikely … the entire world's supply chain will stop and everything that the world relies on can go to the end," Oliver Wyman's Qian said. "There could be some systematic issues, not through the financial system, but through the real economy."