Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

14 Jul, 2022

By Siri Hedreen

Carbon capture will play a vital role in the net-zero economy, but the technology must take a back seat to other decarbonization tools, according to a report by a coalition of leaders across the energy, technology, finance and nonprofit sectors.

But even in a supporting role, the carbon capture industry requires massive scale-up, the Energy Transitions Commission said in its July 13 analysis. Assuming a scenario with 100% carbon-free electricity, 85% green hydrogen and low-carbon biomass, the annual rate of carbon dioxide sequestration must increase 250 times over the next three decades, according to the report.

The commission, a London-based think tank, is led by more than four dozen commissioners from the global public and private sectors. The commission includes leaders from companies such as BP PLC, National Grid PLC, Rio Tinto Group and BlackRock Inc. and groups such as the World Resources Institute and the United Nations Foundation.

The group joins a chorus of industry groups and experts, including the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in maintaining that carbon dioxide removal is necessary for net-zero emissions by 2050. "We see it just being really critical to have more technology options on the table than less," U.S. Energy Department official Noah Deich said at a carbon capture event in June. But skeptics question the nascent technology as, at best, a risky investment and, at worst, an excuse to keep emitting.

Putting carbon back in the ground

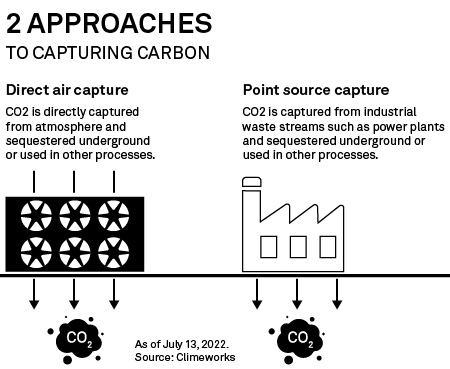

Carbon capture, utilization and storage, or CCUS, refers to the removal of carbon emissions from the atmosphere, as opposed to the abatement of future emissions. Carbon capture technology can be deployed at the point source, intercepting carbon dioxide emissions from smokestacks, or as a stand-alone infrastructure, vacuuming carbon dioxide from ambient air. The captured carbon can be used for industrial purposes or piped to a permanent underground storage site.

But according to the commission, CCUS cannot, and should not, be relied upon too much. "The vast majority of required emission reductions can be achieved through levers other than CCUS," the report said.

Instead, the commission identified three contexts in which CCUS will play a "vital but limited" role, some of which can be achieved through nature-based solutions such as reforestation.

The first context is as a mitigation tool for hard-to-decarbonize sectors, such as the steel, cement and chemicals industries. CCUS can also be used to meet global "carbon budget" goals as the effects of climate change are already being felt. While point-source capture may produce net-zero emissions at best, direct air capture may be needed to remove the carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere. The third context for CCUS is in regions and sectors, such as hydrogen production, where the technology is cheaper than other forms of decarbonization.

"Even when it is not technically essential, CCUS may be the lowest-cost solution in some applications or regions, at least during the transition and in some cases over the long-term," the commission said.

'Limited' role still calls for massive investment

In those three contexts, CCUS technologies must capture 7 gigatons to 10 gigatons of carbon dioxide each year by 2050, up from .04 gigaton in 2020, according to the report.

The Biden administration has pledged support for carbon dioxide removal. In May, the DOE made available $3.5 billion for the development of four direct air capture hubs in the U.S., a program authorized by the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law. Another $2.5 billion has been made available for carbon capture demonstration projects.

But CCUS has a long road ahead. Point-source carbon capture is being demonstrated worldwide, with capture rates as high as 90%. However, few projects have been able to meet this threshold, according to the Energy Transitions Commission. Direct air capture, meanwhile, is energy-intensive and has yet to be deployed at scale

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.