S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

22 Jan, 2021

By Saqib Shah

A Brexit deal struck at the 11th hour has thrust the U.K. in the middle of a politically turbulent tussle over data privacy between its two leading trade partners, the U.S. and the EU.

In the U.K.'s recent deal with the EU finalizing their post-Brexit relationship, an entire chapter was devoted to digital trade. But the biggest decision on data transfers — allowing data to move freely between the two regions without the need for cumbersome safeguards such as individual corporate contracts — has been delayed by the bloc until April, with the ability to extend the deadline by an additional two months. In the interim, the U.K. will continue to get all the perks of an EU member state, including on data, as part of a temporary data adequacy agreement.

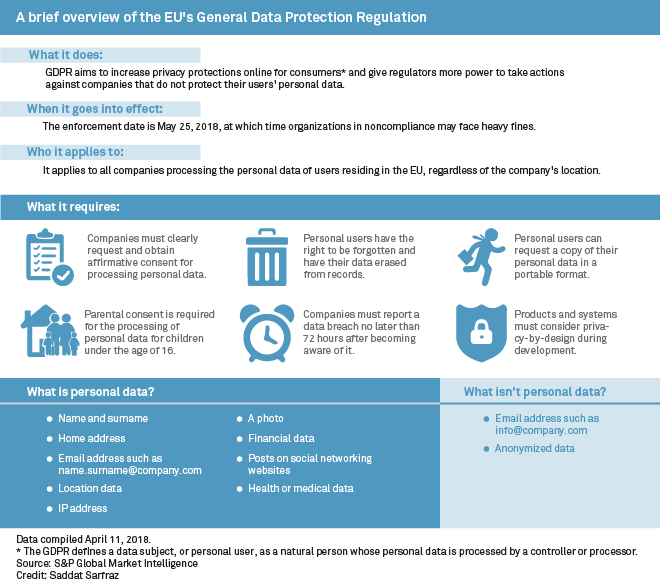

But to ensure and maintain this agreement, Britain may be beholden to the EU's General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR laws, generally viewed as the most stringent data privacy regulations in the world, legal experts said. This in turn could impact the U.K.'s digital trading relationship with its close ally, the U.S., they added.

Defining 'adequate'

|

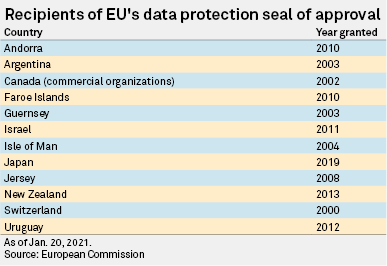

The EU has granted 12 data adequacy agreements, with Japan in 2019 becoming the first country to receive approval post-GDPR. However, concerns over U.S. surveillance laws have seen the bloc's highest court strike down two transatlantic data transfer mechanisms — namely the Safe Harbor treaty and Privacy Shield certification scheme — with a replacement yet to be found.

In the short term, the U.K. is expected to receive adequacy from the EU due to its equivalent data protections under GDPR. But the U.K. risks "jeopardizing" that status if it offers digital trading terms to nations viewed as non-adequate, said Albrecht von Wilucki, a lawyer who focuses on IT and data protection law at Buse Heberer Fromm.

Post Brexit, the EU has jurisdiction to examine Britain's intelligence gathering activities and could pay special attention to its intel-sharing partnership with its Five Eyes allies — including the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand — said Tim Hickman, partner at law firm White & Case.

The European Commission's lead on data adequacy, Bruno Gencarelli, recently stated that government access and onward transfers of data are two areas of scrutiny.

The bloc will be mindful of data ambiguities created by Britain's own adequacy decisions, experts said. "It is not easy to differentiate data held in the U.K., U.S. or EU on individuals," noted Kit Burden, partner and global co-chair of the tech sector at law firm DLA Piper.

"If an EU business can transfer data to the U.K. and then the U.K. grants adequacy to the U.S., suddenly transfers from the EU to the U.S. could become available as a backdoor," Hickman said.

Caught in the middle

But the real danger lies in the adequacy issue becoming a political flashpoint between the three sides, with the U.K. caught between two regions with unique approaches to personal data, according to experts.

Summarizing those differences, the GDPR introduced by the EU and adopted by the U.K. in 2018 is an "omnibus" data protection law that applies to all sectors and companies that offer their services in the region, Hickman explained. Whereas the U.S. has sector-specific legislation on a federal level, with stricter privacy laws in California compared to other states, he said.

"The level of protection in most scenarios is higher under GDPR compared to laws in any other part of the world," Hickman noted.

The U.S. may push the U.K. to grant it data adequacy as part of its digital trading terms in a future trade deal, experts said. It may find it easier negotiating an agreement with Britain and then broaching the EU and its board of data protection authorities, David Saunders, co-chair of the data privacy and cybersecurity practice at law firm Jenner & Block, said.

But to trade freely with the U.S., the U.K. would have to recognize its surveillance laws and run the risk of "annoying" the bloc, especially if the latter takes a "hard line" on transatlantic data flows, according to DLA Piper's Burden.

"Data could become a political football with the U.K. caught in the middle," Burden said. "We are no longer bound by the EU's adequacy decisions. We will roll them over in the first instance, but going forward we will need to make our own decision every time."

A new EU/US framework

Therefore, the best case scenario for Britain is for the EU and U.S. to resolve their differences by adopting a new data transfer framework, experts said. A solution would allow the U.K. to essentially adopt the same method for its own transatlantic data transfers, according to Saunders.

"If the EU and U.S. can agree to a new Privacy Shield, that would relieve a lot of pressure because the U.K. can copycat that without repercussion from the EU," Saunders explained.

Six months have passed since the Privacy Shield was struck down by the European Court of Justice, but there is renewed hope that the two sides will come to an agreement, even if it is a short-term solution, with a new administration in the U.S., said Caitlin Fennessy, the former Privacy Shield director at the U.S. Department of Commerce.

A temporary solution could see President Joe Biden sign an executive order addressing the surveillance issue that resulted in the Court's decision to strike down the Privacy Shield, she said.

For Burden, the potential political scenarios in the transatlantic could be viewed as a microcosm for the data conflicts that lie ahead. "The same way oil drove economic and military conflict, data is likely to generate similar challenges in the next 20 to 30 years," he cautioned.