Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

11 Jul, 2022

| Bolivia's Salar de Uyuni contains the world's richest reserves of lithium, which is critical to the global energy transition, but those resources have remained largely untapped Source: Anton Petrus/Moment via Getty Images |

In the lithium rush unfolding in South America, Bolivia has lagged Argentina and Chile, its neighbors in the Lithium Triangle. Now, President Luis Arce is trying to change that.

The president is trying to bring Bolivia's rich lithium resources to the world market, but using new technology that avoids the environmental and social ills that have accompanied the industry's growth in Chile. In April 2021, Arce called for proposals from companies using direct lithium extraction, or DLE, technology to launch pilot programs.

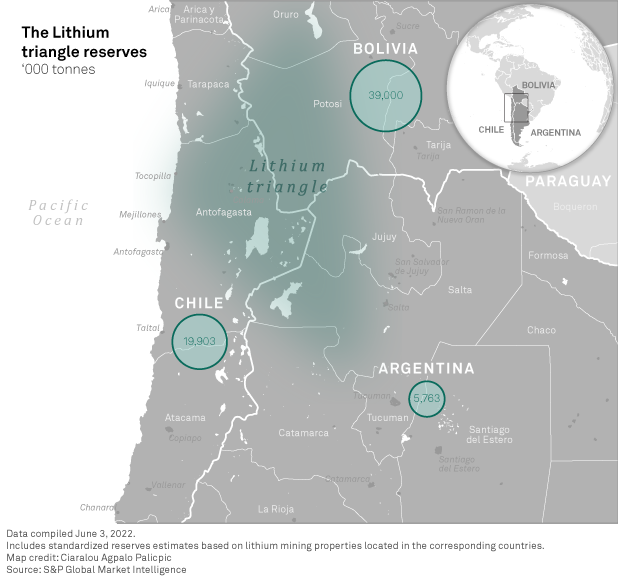

Bolivia's vast salt flats harbor an estimated 39 million tonnes

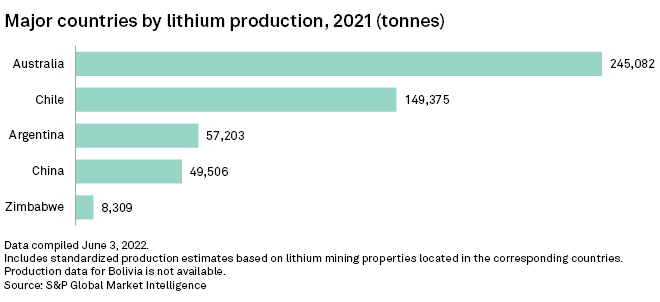

Chile is the second-largest global lithium producer and had output of nearly 150,000 tonnes in 2021, while commercial production in Bolivia, which hosts the world's largest recoverable reserves of lithium, was negligible. Past governments have attempted to set policies to encourage extraction only to botch the process in the end.

Arce aims to have Bolivia producing up to 40% of the world's supply by 2030, a hugely ambitious goal that would make the country "the world capital of lithium," the president has said. Arce needs foreign expertise and capital to achieve these targets, yet the government's policies place strict rules on outside investment, including a requirement that every project be majority-owned by the state.

"The development of the lithium industry in Bolivia has been a key government objective since the beginning of the government of Evo Morales (2006-2019)," said Johanna Maris, a senior analyst for Latin America country risk at S&P Global Market Intelligence. "The government has been well aware of growing global demand for lithium and the increasing value of the resource."

'The critical bottleneck'

What Bolivia has, everyone wants. Suitors for the vast reserves thought to underlie the Salar de Uyuni in southwestern Bolivia include Florida-based startup Energy Exploration Technologies Inc. and California's Lilac Solutions Inc. Both offer direct extraction technology, which aims to extract lithium from brine using far less energy and with lower environmental costs.

The DLE project began in April 2021 will see companies competing to commercialize operations in the country, overseen by the country's Ministry of Hydrocarbons and Energy and the state-owned Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB), or Lithium Deposits of Bolivia. The program marks the beginning of what the government hopes will be a lucrative new industry for Bolivia, whose 2020 GDP was $40.41 billion, compared to Chile's $317.06 billion, according to the World Bank.

YLB officials did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Eight companies made Bolivia's first cut, and the ministry eliminated EnergyX in the second round of selection. The company said in a news release that it was eliminated because it was 10 minutes late submitting its proposal. Lilac Solutions is among the companies moving forward. The remaining suitors come from Russia, China and the U.S.

"Electric vehicle companies are putting tens of billions of dollars into battery manufacturing factories," said David Snydacker, CEO and founder of Lilac Solutions, which uses a new ion exchange technology to extract lithium from brines without the need for evaporation ponds. "Here in the U.S., battery-makers are partnering with Japanese and South Korean companies to bring that manufacturing onshore, but those factories are going to be lacking in raw materials. Lithium is the critical bottleneck."

"[DLE] technology is a step toward innovation that will provide important opportunities to generate technical and technological growth, and that is what we are here to present today," Minister of Hydrocarbons and Energy Franklin Molina said at a meeting with lithium production companies.

First, Lilac Solutions and the other DLE providers must prove themselves in the harsh environment of Bolivia's salt flats. While DLE technology has shown promise in small-scale, pilot projects, it is untested for commercial-scale production. Bolivia lacks the infrastructure and technical know-how that neighbors Argentina and Chile rely on. In addition, the brine of the Salar de Uyuni has high concentrations of magnesium, complicating the extraction of pure lithium concentrate.

False starts

Those false starts have resulted from "flipflopping on strategy, primarily," said Christopher Ecclestone, a principal and mining strategist at London-based consultancy Hallgarten & Co. "They've never been sure particularly about how they want to do it or who they want to partner with to do it."

Bolivia's lithium industry has also been held back by the government's overarching ambition to produce finished lithium-ion batteries as well as raw materials.

"YLB has been spread too thin and tasked to develop too many complex projects simultaneously and consequently has not made very much progress in the last decade," Payne Institute analysts wrote in a June 2020 report. "Though multiple deals with companies from around the globe have been very publicly signed to develop their brine resources, they have not succeeded."

Trying to get moving

The Arce government needs money and technical expertise from foreign partners to build a viable lithium industry. But the government is making the process challenging, Maris said.

The Bolivian government is making "efforts to minimize foreign participation in the lithium development process through a requirement for all development agreements to have a majority state participation," Maris said. The government also requires "industrialization and lithium battery production in the country rather than exporting the raw material, which has significantly slowed the process and likely reduced interest from some firms preferring to manufacture elsewhere."

So far, foreign companies have shown a willingness to comply with Arce's requirements in an effort to extract Bolivia's lithium riches. But the president is hardly pulling all the levers.

"Arce could do much more to make lithium the central element of his agenda, not just for current economic recovery but for a long-term historical legacy, since lithium could transform all of Bolivia into a middle-income country," Diego von Vacano said in an email. Von Vacano is a professor of political science at Texas A&M University and an adviser to the Arce government on natural resources policy.

"The recent conclusion of the DLE [selection] phase was an important positive phase, but it was not without its problems of transparency, clarity and lack of uniformity of procedures," the adviser said.

To finally build a world-class lithium industry, Arce must avoid the missteps of his predecessors, Ecclestone said. "Bolivia could produce the largest share [of the world's lithium supply]; it's got the potential, it's enormous. But there's nothing different now except a different government. The policy confusion goes on."

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.