Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

1 Apr, 2022

By Stefan Modrich and David DiMolfetta

Experts believe that while new EU regulations associated with the Digital Markets Act could have a significant impact on affected companies, enforcement will be the main determinant in ensuring the laws are effective.

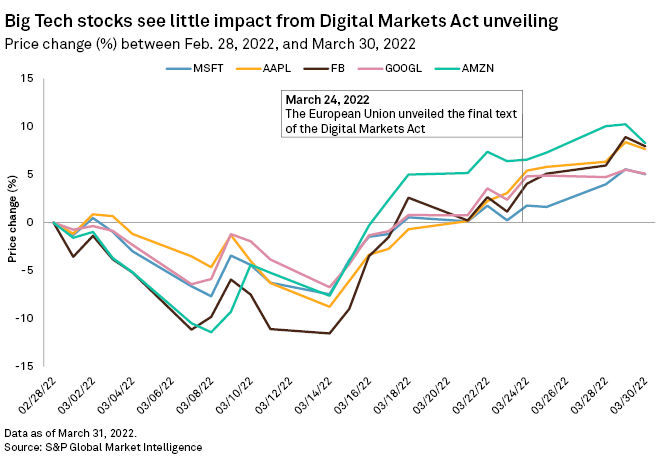

The European Council and European Parliament on March 24 approved the Digital Markets Act, or DMA, a framework of new initiatives intended to curb the dominance of Big Tech companies and related entities in Europe's digital landscape.

The DMA's measures are designed to reduce the power of digital "gatekeepers," which are companies considered to hold too much market concentration, thereby preventing competitors from entering a market. The DMA does so by determining which businesses can interact on or alongside their platforms and the way they can operate.

Defining the gatekeepers

The DMA establishes parameters for platforms to qualify as gatekeepers that could stifle competition. The threshold for companies being targeted includes a market cap of at least €75 billion, or approximately $83 billion, or companies that have earned at least €7.5 billion, or approximately $8.3 billion, in annual revenue within the last three years. A company must also have a minimum of 45 million monthly end users or 10,000 business users within the EU to be considered a gatekeeper. This puts tech giants such as Apple Inc. and Meta Platforms Inc. well within the DMA's crosshairs.

A gatekeeper platform must also control one or more of its core services in at least three EU member states, including marketplaces and app stores, search engines, social media, cloud services, advertising services, voice assistants and web browsers.

"If you can't get into those venues, you do not have a viable product," said Paige Bartley, senior research analyst of data management at 451 Research. "If I'm an independent developer and I can't get into the Apple App Store and I can't get into the Google Play Store, I'm officially erased from the market. I don't exist."

Other elements of the bill's language pertaining to gatekeepers are less clear. The DMA exempts small and medium-sized enterprises. But the law also allows for the potential of imposing certain conditions on an "emerging gatekeeper," which may not qualify based on the current criteria.

More than 10,000 SMEs are operating in the EU's digital economy, according to the European Council.

The most important part of the DMA is a provision that indicates designated gatekeeper companies would not be allowed to combine and cross-utilize user data from different parts of their business to form targeted advertisements, according to Johnny Ryan, senior fellow at the Irish Council for Civil Liberties and a senior fellow at U.S. pro-competition group Open Markets Institute.

For example, Google parent Alphabet Inc. may use location data to determine if an individual has an illness when they visit a certain physician or to determine a user's religion they visit a house of worship.

The effects of this cascade into hefty, data-driven advertising frameworks for dominant platforms, locking smaller players out, Ryan said. The DMA would prevent this.

The law also allows the European Commission to directly supervise whether a gatekeeper breaks rules concerning cross-data processing. Those rules exist under the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, but Ryan said they have not been enforced due to ongoing procedures against tech companies at smaller GDPR supervisory authorities such as the Irish Data Protection Commission.

Flexing regulatory muscles

The DMA, alongside the related Digital Services Act, was introduced by the European Commission in December 2020. EU member states unanimously approved the regulations in November 2021. Pending final revisions, it is expected to take effect in January 2023.

The legislation could be a paradigm shift for regulators looking to flex financial penalty authority and for Big Tech companies looking to avoid steep fines for transgressions.

Unlike the up-to-4% cuts from worldwide annual revenue that can be enforced under the GDPR, the DMA would impose penalties of 10% of global revenue and 20% for repeat offenders.

"That's an exorbitant fine," said Dan Caprio, co-founder and chairman of The Providence Group, a Washington, D.C.-based data risk consulting firm.

Caprio also noted the possibility of "significant" unintended consequences for any monetary penalties.

"In Europe, if you're below those financial penalty thresholds, you're probably going to change your business practice to stabilize your thresholds, even if it means losing out on growth and new markets and new opportunities," Caprio said.

Bartley agreed, saying the DMA could create a perverse incentive for a promising tech company not to reach gatekeeper status to avoid triggering fines or other penalties.

"When you create this binary distinction of more restrictive rules that are supposed to support a competitive market but also try to foster an environment where market inference platforms can grow, you may have a growing technology company that is gaining more users, which will reach a point where they cross the threshold," Bartley said.

The strength of the DMA rests in its ability to force companies that violate its rules to change their behavior, said the Irish Council for Civil Liberties' Ryan. But Ryan said a lack of assertiveness by the EU in enforcing DMA rules could see history repeating as with its GDPR predecessor, which ultimately just scares or fines companies that break its laws.

"Fines, of course, are an embarrassment. But if you can dominate the market and just pay a fine, why wouldn't you do so?" Ryan said.

Ryan also voiced concern that the DMA could turn out to have some of the same vulnerabilities as GDPR and that any law on paper is meaningless unless it is imposed.

"Europe invested a lot of its credibility in the GDPR," Ryan said. "But now the commission has forgotten about it. ... Everything depends on enforcement. There's no appetite, judging by GDPR. There's no appetite at the European Commission to see that [the regulations] are applied."

Diverging approaches

While some language in the DMA is mirrored by ongoing U.S.-based legislation designed to rein in Big Tech, the regulatory methods and structure employed in the U.S. and in Europe will continue to be distinct in several ways.

Tech companies in the U.S. tend to face more class-action lawsuits in which gray areas are sorted out via court precedent, according to Bartley. Industries with a strong history and culture of regulation such as healthcare and finance have been more receptive to stringent guidelines, Bartley said.

Caprio of The Providence Group said EU officials have been surprised by the pushback from U.S. officials, who are concerned about the disproportionate impact on U.S.-based companies. While there are some parallels between the U.S. and its largest trading partner, Caprio does not anticipate a regulatory convergence between the two.

Bartley and Ryan emphasized that regulations on the scale of the DMA will take years to enforce and eventually measure efficacy, though they could set an example for future U.S. procedures on antitrust and data privacy matters.

But if no enforcement exists, the DMA will not be a paragon for American legislation either, Ryan said.

Tech giants brace for enhanced scrutiny

Apple and Google broadly endorsed the DMA in statements sent March 25 to S&P Global Market Intelligence, but the two tech giants also shared similar concerns regarding the scope of the regulations.

"While we support many of the DMA's ambitions around consumer choice and interoperability, we remain concerned that some of the rules could reduce innovation and the choice available to Europeans," a Google spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement.

Apple worries that the DMA would create unnecessary privacy and security vulnerabilities for its users, a company spokesperson said in an email. "Other provisions will prohibit us from charging for intellectual property, in which we invest a great deal."

An Amazon.com Inc. spokesperson said the company did not have a public position on the DMA and said Amazon is reviewing the legislation and "committed to delivering services that meet our customers' requirements within Europe's evolving regulatory landscape."

Meta did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Casper Klynge, Microsoft Corp. vice president of European government affairs, said Microsoft has been supportive of EU efforts "from the start."

"Open platforms are important to innovate for the future," Klynge said in an emailed statement. "The new European gatekeeper rules will ensure that large online intermediaries, including Microsoft, do more to adapt and make #TechFit4Europe."

The Providence Group's Caprio said Microsoft appears to have calculated that the potential risk the DMA poses is much greater for its competitors. Microsoft has grown and matured since experiencing its own period of antitrust scrutiny in the 1990s, and its more cooperative stance with U.S. regulators could be a model for other Big Tech competitors, Caprio said.

The U.S. government has long been one of Microsoft's largest clients, having used its Office suite of products and Azure cloud service. Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services share a contract with the U.S. Defense Department, the Pentagon announced in July 2021.

Next steps

The provisional agreement for the DMA is subject to approval by the European Council and the European Parliament. European Council President Charles Michel must submit the agreement to the Permanent Representatives Committee for approval. The text will come into force 20 days after it is published in the EU Official Journal, and the rules will apply six months after that publication date.

EU officials also expect to reach an agreement on the broader Digital Services Act, which encompasses online intermediaries and platforms, according to a news release.

451 Research is part of S&P Global Market Intelligence.