Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

15 Jan, 2021

By Evan Fallor

President-elect Joe Biden's economic relief proposal would sharply expedite the U.S. economic recovery from the coronavirus, but its $1.9 trillion cost to the nation's balance sheet has economists grappling with the trade-off of short-term boost and future debt reckoning.

Biden's plan, unveiled in a televised address late Jan. 14, includes funding for $1,400 additional one-time relief checks for those earning less than $75,000 per year, as well as an increase in the supplemental unemployment benefit to $400 per week from $300, with the benefit extended to September. The moratorium on evictions and foreclosures would also extend until September, and the plan calls for an increase of the minimum wage to $15 per hour. The proposed package also includes more than $400 billion in direct relief to address fallout from the coronavirus, including $350 billion in aid for ailing state and local governments.

Economists said the need for relief for the unemployed overrides the long-term deficit concerns of the spending package, but only for now, with the added debt burden needing to be addressed later.

"In terms of pushing the economy to pre-pandemic levels, this will certainly help achieve that even faster than predicted," said Erik Lundh, senior economist for the Conference Board, a business-funded research group. "The downside risk, however, is it renews concerns about the government debt that climbed quite rapidly over the past year. That's a longer-term concern." His latest forecast puts U.S. economic output back at pre-pandemic levels in October, but this package, if implemented, could push that milestone to mid-summer.

Unemployment extension seen as most crucial

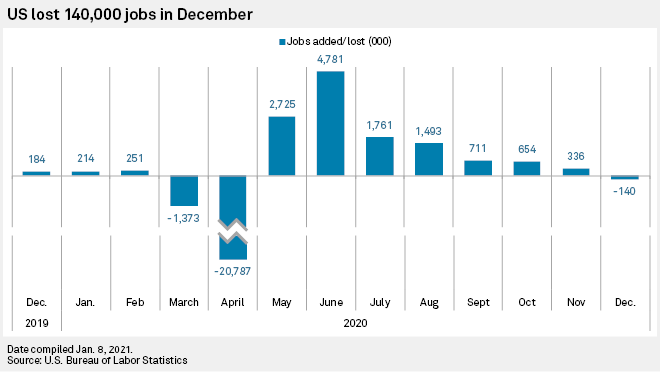

The relief package comes as economic headwinds strengthen against an already ailing U.S. economy as COVID-19 spread accelerates. Employment declined by 140,000 jobs in December 2020, and 965,000 Americans filed initial jobless claims for the week ended Jan. 9, the highest weekly tally since August 2020. The past week brought 1.7 million new cases, and more than 130,000 Americans are hospitalized with COVID-19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The package, if approved in its current form, would boost first-quarter GDP growth over the current S&P Global Ratings baseline estimate of 0.8%, said Beth Ann Bovino, U.S. chief economist at the ratings provider.

"And depending on how long it is in place, the stimulus could provide economic support later in the year," Bovino said in an interview. "However, much of the stimulus mentioned in this proposal is temporary short-term ... measures aimed to accelerate 'filling the demand hole.' But they don't necessarily pay for themselves."

The one-time $1,400 cash payments — which combined with the $600 checks included in last month's bill would reach the $2,000 level sought by Democrats and President Donald Trump — are grabbing headlines, but several economists told S&P Global Market Intelligence that this element is not as vital as the extension of unemployment benefits.

"When I heard long-term unemployment benefits [in Biden's plan], I loved it, because this is going to be a longer-term problem," Rajeev Dhawan, director of the economic forecasting center at Georgia State University, said in an interview. "When the virus is bad, people are getting laid off in contact industries [such as retail], and you have to give them unemployment insurance to hold them over. This will be a benefit because the virus is about to put a crimp on the economy, especially on those contact sectors."

The $1,400 checks would likely be saved initially by recipients, limiting the initial impact, but could "fuel a consumer boom" when the U.S. economy reopens in full, said James Knightley, chief international economist for ING Economics. He said the relief package "reinforces" ING Economics' estimate of 5% GDP growth in 2021.

"Providing an extra stimulus check will help those struggling with bills, and extending unemployment benefits through the end of September will also help Americans who need more time to get on their feet," S&P Global Ratings' Bovino said. "With almost 1 million Americans signing up for unemployment benefit checks, that helping hand is sorely needed."

An opening bid

Biden's plan will first need to clear a 50-50 Senate that leans in favor of Democrats only because of Vice President-elect Kamala Harris' potential tiebreaking vote as president of the Senate. Its consideration would come mere weeks after Congress passed and Trump signed a $900 billion package that includes $150 billion for one-time $600 checks for those earning under $75,000 annually, as well as $115 billion in extended emergency unemployment benefits for 11 weeks. That bill was largely seen as a stopgap measure to keep the economy afloat before more stimulus could be injected.

"To pass something so quickly on the heels of this is a tall task," Michael Pugliese, an economist and vice president for Wells Fargo Securities, said in an interview. "With direct reconciliation, there are major headaches, and the Democrats would need to stick together, and all of the rules that come along with it. It is not easy to do, and this serves more as an opening bid."

If the Senate considers the legislation as part of the reconciliation process, it would require a bare majority instead of the 60 votes needed to achieve cloture.

Republicans are likely to oppose the increase in minimum wage and the $350 billion to be allotted to state and local governments to offset budget shortfalls. Because there are no tax increases to fund the ambitious bill, that means more of an increase to government borrowing, which already hit an all-time high in 2020.

Pugliese sees the proposal more as an opening point for negotiations with Republicans and said the natural impetus to get either a complete package or piecemeal legislation through would not come until mid-March, when the extra $300 weekly unemployment insurance benefits expire.

In a speech announcing the plan Jan. 14, Biden acknowledged that his plan "does not come cheaply," but that "failure to [pass the plan] will cost us dearly."

The final price tag of the package may end up between $900 billion and the proposed $1.9 trillion, but it is relief that is needed, economists said.

"2020 was all about managing the downside risk, and how bad is it going to get," Lundh said. "I would rather be on the flip side of that, and that is what I am looking at in 2021 — how much are we going to recover? Seeing a big number like this makes one a little more optimistic over the next 11 months."