Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

8 Jan, 2021

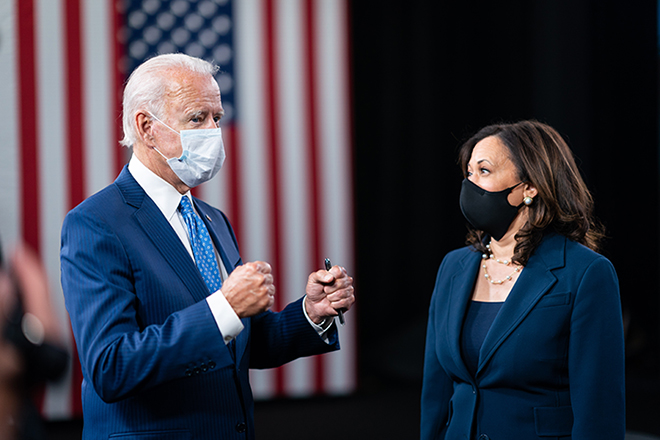

| U.S. President-elect Joe Biden stands with Vice President-elect Kamala Harris. Source: Biden Campaign, photo by Adam Schultz |

Following Georgia's U.S. Senate elections, a Democrat-controlled Congress will gear up to consider President-elect Joe Biden's nominees to lead key agencies and develop additional coronavirus relief legislation that could include clean energy provisions.

But Democrats' razor-thin majority in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives will require them to find common ground with the GOP, sources said.

Georgia Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff defeated Republican incumbents Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue in Jan. 5 runoff elections. As a result, the Senate will be divided 50/50 between the Republican and Democratic caucuses, with Democratic Vice President-elect Kamala Harris able to cast a tie-breaking vote once she and Biden are sworn in Jan. 20.

With unified control of Congress and the White House, Democrats are hoping to advance ambitious climate legislation that could help the U.S. slash carbon dioxide emissions.

U.S. Sen. Tom Carper, D-Del., the top Democrat on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, "knows the U.S. needs to achieve net-zero emissions economy-wide by no later than 2050, so you can expect EPW will prioritize efforts that put the country on a path to achieve that goal," a Carper spokesperson said Jan. 7.

Nominations

Although more comprehensive climate legislation will take time to form, Congress' near-term priorities include confirming Biden and Harris' nominees for energy-focused roles. That task should be easier now that Democrats have the upper hand in the Senate, albeit a narrow one.

Biden's choice for Interior secretary, U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland, D-N.M., may face Republican ire over her calls to ban hydraulic fracturing on public lands, said Eric Washburn, a consultant for Bracewell LLP's Policy Resolution Group and a former Democratic staff director for the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee.

But with Haaland the first Native American nominated for the position, "there are a number of Republican Senators from states with large Native American populations — Alaska, North and South Dakota, Montana — who may find it politically hard to oppose her nomination," Washburn said.

Other Biden nominees, including Energy Secretary nominee Jennifer Granholm and Biden's choice for EPA administrator, Michael Regan, are also likely to avoid confirmation battles despite a tightly split Senate.

"[Granholm's] record as a former governor of Michigan, combined with her deep understanding of energy policy issues, should carry her through the process," Washburn said.

And Regan, who heads the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, "does not appear to come with much partisan baggage, having worked at the EPA under both Democratic and Republican Administrations," Washburn added. "While he has run into some turbulence in North Carolina in dealing with the electric utility industry on coal ash issues, he has not previously been associated with the high-profile, hardball partisan politics of [Washington, D.C.], and I would be surprised if his confirmation is seriously threatened."

Biden does not have any immediate vacancies to fill at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which has a 3-2 Republican majority. But GOP Commissioner Neil Chatterjee's term expires at the end of June, giving Biden a chance to select someone who would swing FERC to a Democratic majority.

Senate leaders have yet to announce committee procedures for the new Congress. Former Capitol Hill staff have said the Senate could establish a similar process to what the Chamber did with a 50/50 split in 2001. During that Congress, Senate leaders agreed that each party would have equal committee representation.

And tied committee votes could reach the full Senate using a privileged discharge motion. Such motions to discharge a tied vote from a committee are only subject to four hours of debate on the Senate floor, after which the full chamber can vote on the motion, with the vice president able to cast a deciding vote if the full Senate is split on the motion.

Near-term legislation

The Democrats' newly reclaimed control over the upper chamber does not guarantee easy passage for big climate and clean energy legislation. Democrats have a narrower majority in the House than last Congress, and political polarization is still rampant across Washington, D.C.

That tension may "strengthen ideological linkages between parties and fuels: Democrats could become even more the champions of green energy and transition technologies, and Republicans could become even more the guardians of fossil fuels," according to a Jan. 5 note from the independent research firm ClearView Energy Partners LLC.

In the near term, Biden and Congress will likely prioritize further COVID-19 economic relief measures that could include bipartisan clean energy measures. A slight Democratic majority in the Senate may garner support for a "recovery-focused stimulus package that includes robust incentives for green energy and transition technologies," ClearView said.

In late December 2020, President Donald Trump signed a combined coronavirus aid bill and omnibus package that included hefty authorizations for U.S. Energy Department research programs and new and expanded tax credits for renewable resources and carbon capture technologies. But the package left out other clean energy priorities, including an expansion of the electric vehicle purchase tax credit backed by Biden and congressional Democrats. Such measures could make their way into a new aid bill.

"There's been a very vocal and growing push to include as much green spending in these stimulus measures as possible," said Lachlan Carey, an associate fellow of the Center for Strategic and International Studies' energy security and climate change program.

The upcoming budget and appropriations cycle for the 2022 fiscal year could also give Congress a chance to distribute funds for Energy Department research programs that were authorized in the COVID-19 relief measure signed in December 2020. The bill contained $35 billion in authorizations for federal research and development but did not actually fund those programs.

"I think it will be really important for Congress to follow through on the energy package to make sure we take advantage of those opportunities," said Brad Townsend, director of strategic initiatives at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

Also in the near term, the Democrat-led Legislature may invoke the Congressional Review Act to roll back regulations the Trump administration finalized in recent months and perhaps amend corporate tax rates, especially those pertaining to fossil fuel companies.