Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

23 Sep, 2021

Investors shrugged off this week's stumble in equities as a speedbump in the ongoing, historic stock market rally. But cracks in the run have widened in September, and market analysts see increasing potential for a sizable correction.

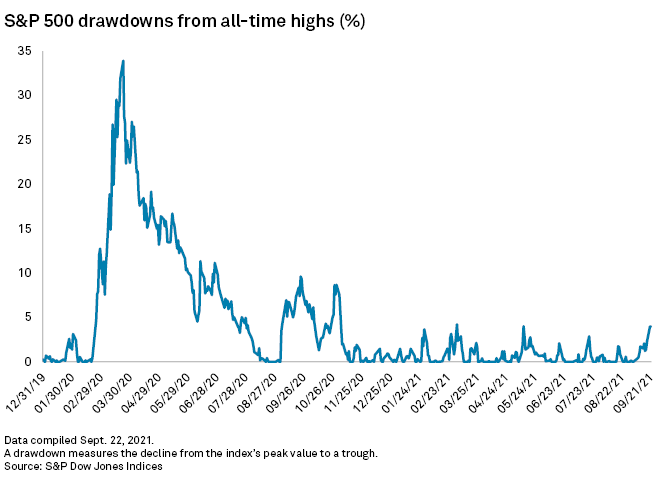

The S&P 500 has not fallen more than 5% from an all-time high value since November 2020. But signs of market weakness are starting to emerge, stemming from expected changes in U.S. monetary and fiscal policies to ongoing business challenges from the pandemic. After hitting a new high earlier this month, the S&P 500 fell 4% below that peak on Sept. 20, stoking concerns of a further fall.

"We are overdue for a more meaningful correction than the ones we have had so far in 2021," said Matt Peron, director of research at Janus Henderson Investors, in an interview. "While I don't think we are beginning a bear market I do see some scope for continued weakness."

The S&P 500 closed up nearly 1% on Sept. 22 and had rallied as much as 1.4% during the day. The partial recovery followed an announcement that the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee committed to continuing its ultra-loose monetary policy in the near term while stating that a slowdown in its $120 billion in monthly asset purchases "may soon be warranted."

Other stock indexes also rallied roughly 1.4% each following the release of the FOMC's statement. Earlier this week, the Dow Jones Industrial Average and tech-heavy Nasdaq composite index fell to 4.3% and 3.8% lower, respectively, than their peaks at the beginning of September.

The 4% drawdowns in the S&P 500 this week were the largest declines since May 12, when the index also tumbled about 4% from its peak at the time. A drawdown is a measure of how far the index has fallen from an all-time high.

A much larger correction could hit soon with the Fed's ultra-loose monetary policy coming to a close and U.S. stock valuations at a record high, said John Davi, chief investment officer at Astoria Portfolio Advisors.

"A sell-off is natural," Davi said in an interview. "We've been expecting one for a while."

Signs of volatility

Since the start of the year, the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings, or CAPE, ratio for the S&P 500 has risen about 10% and is less than 15% from its height during the dot-com boom in late 1999. The ratio is used to determine whether stocks are undervalued or overvalued. It is calculated by dividing stock prices by trailing 10-year average earnings, as opposed to the standard price-to-earnings ratio, which divides stock prices by analysts' earnings forecasts.

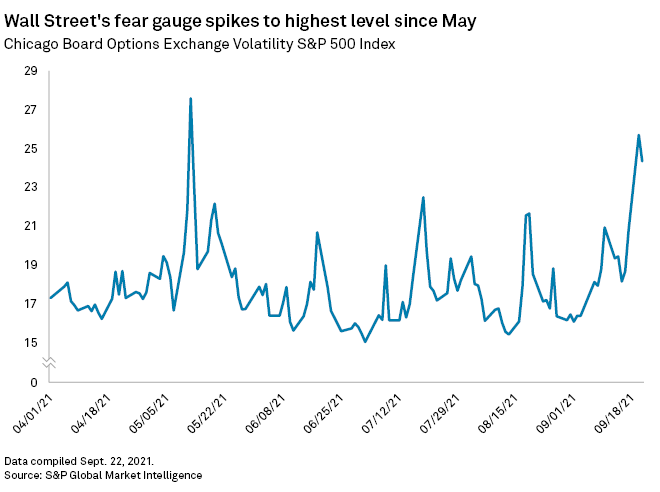

Fears of a correction pushed the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index, or VIX, up to its highest level since May 12. The index is commonly referred to as Wall Street's "fear gauge" and measures stock market volatility expectations based on S&P 500 index options.

Peron with Janus Henderson Investors said there were multiple reasons for this jump, including the forthcoming plans from the Fed to taper its $120 billion in monthly securities purchases, fears of contagion from a potential default of China Evergrande Group and the impact of supply constraints on economic growth.

"At the highest level, I don't see any of these as 'cycle ending' and see this as a healthy pause and allows market to reset and consolidate for a few weeks," Peron said.

Stocks could stumble in coming weeks over several other hurdles, said Tom Essaye, a trader and founder of financial research firm The Sevens Report. These include a potential government shutdown, a possible breach of the U.S. debt ceiling or a significant movement on proposed tax hikes. Volatility in the market will remain until there is more clarity on these issues, Essaye wrote in a Sept. 21 note.

"Nothing in this market makes us think we're staring at a bearish gamechanger at this point," Essaye wrote. "As such, we continue to look to weather the volatility with the expectation of the rally likely resuming into year-end."

High-yield bonds point to optimism

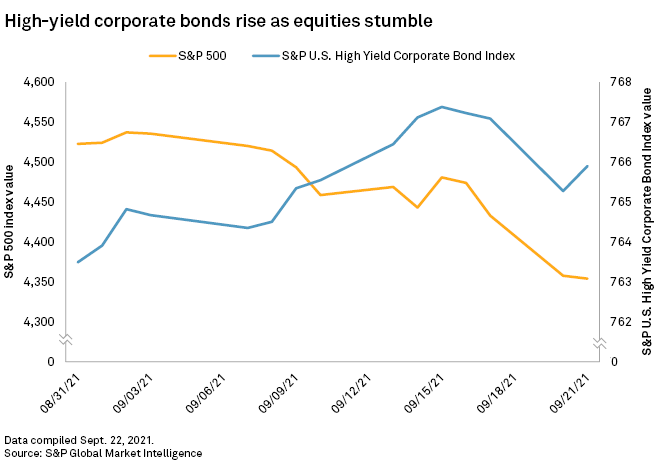

One sign that the equity market rally may continue is the ongoing increase in high-yield corporate bonds, said Paul Schatz, president of Heritage Capital.

"High-yield bonds just keep quietly chugging higher which may be the most important sign that nothing big on the downside is out there," Schatz said in an interview.

Schatz called high-yield bonds the "canary in the coal mine," for future stock market performance since they are the riskiest bonds and tend to reflect brewing market turmoil before stocks.