Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

13 Jul, 2021

By Sanne Wass

Commercial banks will play "a very important role" in Sweden's project to create a central bank digital currency despite concerns that it could erode traditional lenders' deposit bases, according to a payment executive at Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ).

Handelsbanken, Sweden's largest bank by assets, has become the first commercial lender to join a project by the Swedish central bank, or Riksbank, to test a so-called "e-krona" — a digital version of cash. Governments around the world from Cambodia to China and the Bahamas are exploring central bank digital currencies, or CBDCs, with about 60% of central banks conducting experiments or proofs of concept, and 14% moving to development and pilots, according to the Bank for International Settlements, a global body representing central banks.

A CBDC could become a "game-changer" for Swedish society, said Benny Johansson, Handelsbanken's head of Nordic payments, in an interview. Handelsbanken will use the pilot to evaluate the potential benefits an e-krona could bring to the bank and its customers, Johansson said.

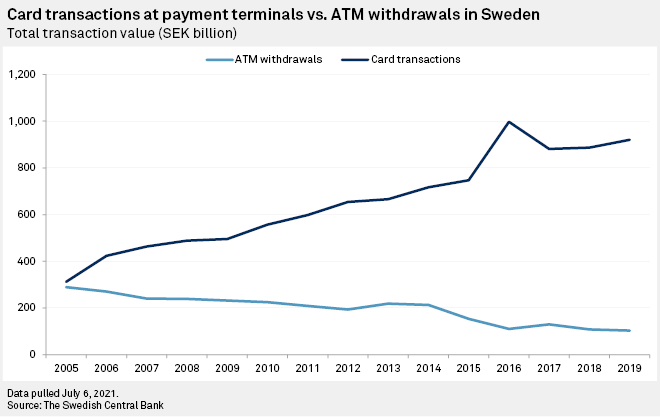

In Sweden, the e-krona is the Riksbank's response to a decline in the usage of cash, the only central bank-issued money in the country, which has caused its direct role in the payments market to diminish. Cash in circulation in Sweden now stands at just over 1% of GDP, among the lowest in the world, according to Carl-Andreas Claussen, a senior adviser at the Riksbank. If the development continues, the Scandinavian country could be completely cashless within a decade or two, Claussen said.

Erosion of banks' deposits

While CBDCs may help central banks to regain lost ground in the payments market, commercial players worry where such developments would leave them. If central banks could offer a bank account directly to members of the public, what need would there be for a traditional lender?

In Sweden, Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB (publ) CFO Masih Yazdi recently warned that if customers moved their money out of deposit accounts and into the e-krona, it could deprive banks of funding and risk instability in the wider system.

Johansson at Handelsbanken does not see any major risk of this happening under the e-krona's current design. He agreed in principle that there could be a long-term risk for commercial banks, in any market, if CBDCs were to be widely accepted. But whether such risk materializes will depend on how the CBDC is designed and under what conditions it is offered, he said.

The design evaluated by the Riksbank is a token-based system, which Johansson said will make the e-krona

"I think it's in everyone's interest, both the regulator, the Riksbank, the banks and the consumers, to have stability in the financial system. And seeing large outflows of bank accounts is not beneficial to the stability of the financial system," Johansson said.

Banks' role

The Riksbank will ultimately have to offer a business model that is valuable for private actors such as banks or financial technology companies as their support will be crucial to the success of the e-krona, according Niklas Arvidsson, a professor at Stockholm's KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

"The Riksbank cannot do it on its own," Arvidsson said in an interview. "It needs the commercial banks to invest in the e-krona as a service. And that also means that they must have an interest in doing it."

Johansson said commercial banks will play "a very important role in the e-krona project," as they, under the current setup, will take on a role as participants and run their own nodes on a blockchain network, where the e-krona will reside and be distributed to the end-user. "The Riksbank won't be the ones holding the e-krona accounts for the customers," Johansson said.

The Swedish central bank echoes this sentiment, with Claussen saying in an email that "banks are expected to play an important part in this" by making sure that exchanges between the e-krona and private money "become a seamless experience." Depending on the technical setup, banks may also be asked to verify transactions and keep track of end-users' e-krona belongings, he said.

Claussen said the Riksbank has no ambition for the e-krona to take over a large share of commercial bank deposits, adding that "the aim is rather likely to be that the e-krona shall have a market share similar to what cash had some years ago," although he did not specify how much that is.

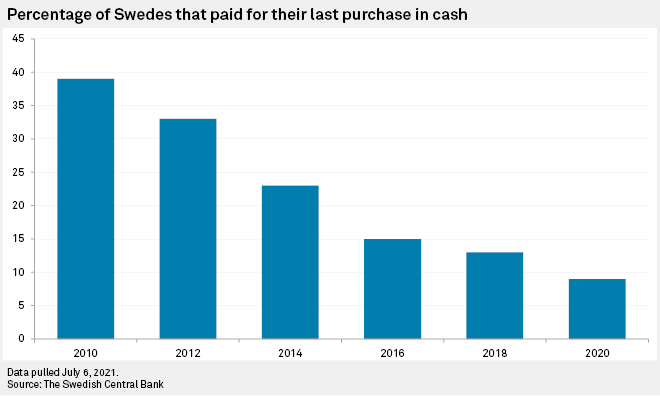

The proportion of Swedes using cash has fallen from around 40% to less than 10% in the past 10 years, according to the Riksbank.

Yet, Claussen hinted that banks could expect intensified competition should the central bank launch such a digital currency. "It is nothing new that the Riksbank competes with commercial banks. Physical cash has always been and still is in direct competition with commercial bank deposits. However, with a CBDC it might be more competitive in this sense as it is digital money and thereby much closer to commercial bank deposits in its design," Claussen said.

CBDC demand in Sweden?

Others believe the Riksbank will face an uphill battle entering a market in which private sector innovation has already brought easily accessible and convenient digital payments to consumers.

"As of today, there is not really any demand for [an e-krona] from consumers or merchants," said payments expert Arvidsson, adding that it is "questionable" if Swedes would see any value in holding digital money issued by the central bank, as opposed to what they hold today.

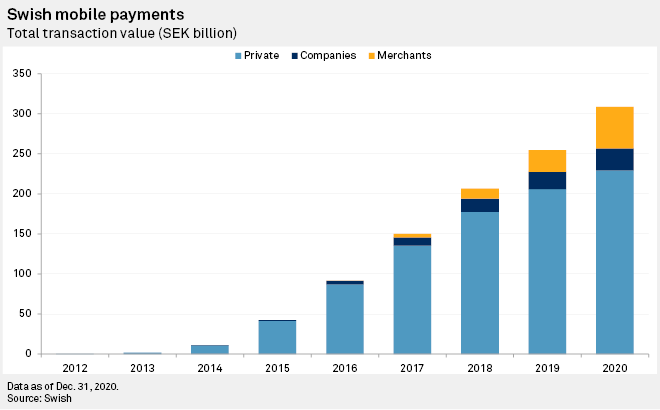

Mobile payment application Swish, for example, is already close to being universally adopted in Sweden. The app, which is run by the country's largest banks and allows Swedes to pay peers instantly from their phone, facilitated more than 300 billion kronor worth of transactions in 2020. That is three times more than Swedes withdrew from ATMs in 2019, the latest available data.

"I don't see that [the e-krona] will benefit our customers in the short run, since we have a very efficient digital payment system in Sweden," said Handelsbanken's Johansson.

Most of the potential benefits to consumers are likely to come in the long run, Johansson said, as the pilot could pave the way for blockchain-based payment innovations in the future and a rethinking of regulation surrounding blockchain technology. For example, the project could be a first step toward establishing a blockchain-based infrastructure between commercial banks, he said.

Yet, there are some features that could give the e-krona a competitive edge. Claussen said the digital currency could offer more privacy than private alternatives, or the option to make offline payments. Policy and design decisions, which are yet to be made, could also make the e-krona more attractive than other means of payments and assets, for example by offering an interest rate on e-krona deposits, Claussen said.