Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

13 Apr, 2022

By Sanne Wass

Financial institutions with no Russian exposure still face significant indirect sanctions risk through the so-called correspondent banking services they provide to other banks.

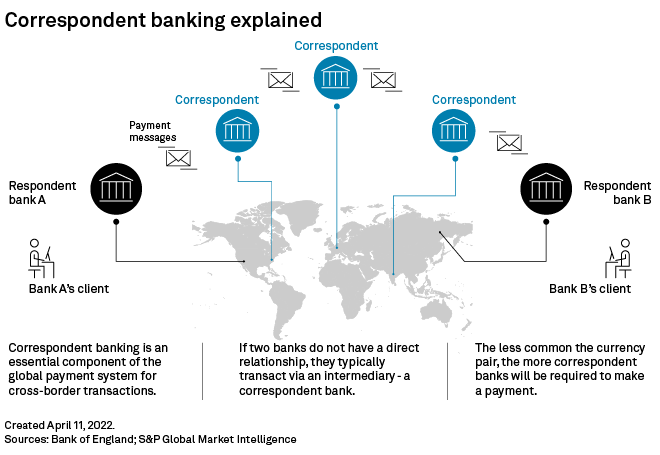

Correspondent banks act as go-betweens in cross-border transactions between banks that lack formal ties, and they rely on "respondent" banks to conduct due diligence on customers. They risk facilitating illicit payments if respondent banks knowingly or unknowingly breach sanctions.

"You trust that your correspondent banking clients' anti-money laundering systems will detect the risk — but what if they don't, and you unknowingly process these funds?" said Eric Li, research director at Coalition Greenwich, an S&P Global-owned research company.

It means banks with no direct exposure to Russia could end up unwittingly facilitating money transfers for sanctioned entities, Li said. The U.S., EU and other governments have imposed sanctions on Russian banks following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

"The risk is real, and it's probably going to, at some point, impact every single bank on this planet," Li said.

Correspondent banks typically have no direct relationships with the underlying parties in a transaction. Their clients, respondent banks, carry out customer checks, including determining beneficial owners or sources of funds.

Some American banks have already cut U.S. dollar clearing services to Western lenders that have stayed in the Russian market, even if they are there legally, according to Daniel Tannebaum, global head of sanctions at consulting firm Oliver Wyman.

"The appetite for absorbing any sort of indirect risk is just zero with some providers," said Tannebaum, who has worked for the U.S. Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control. "If you're involved in the underlying financing of an impermissible transaction and you are a few layers removed from where that potential violation occurs, you still can be held liable."

Banks remaining in Russia

Banks will be especially exposed to indirect sanctions risks through correspondent ties to financial institutions in countries that have strong links to Russia or no sanctions program in place, such as China or India, or Russian lenders that are not sanctioned, Li said.

But Western counterparties may also pose a risk, given that many of them have maintained some presence in Russia, Tannebaum said.

"Correspondent banking due diligence has always been hard enough. This situation makes it impossible," he said.

Banks risk facilitating illicit payments due to deliberate attempts by respondent banks to circumnavigate sanctions or to accidental or administrative errors because the relevant information was not accurate or available, said Rachel Woolley, global director of financial crime at Fenergo, a regulatory technology company.

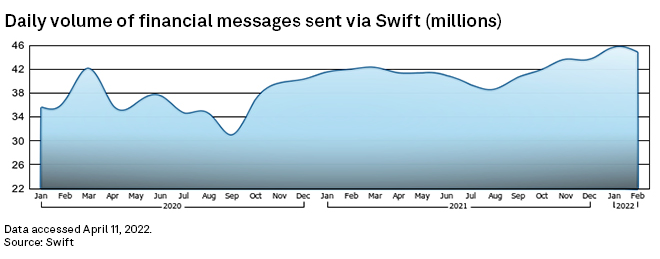

Typically, payment messages sent through Swift will provide some but not all details related to a transaction, Woolley said. For example, they may not include information about beneficial owners of a company.

Lack of transaction information makes it harder for banks' screening software to detect sanctioned activity that comes through correspondent banking ties, said Braddock Stevenson, counsel in the investigations and white collar defense practices at law firm Paul Hastings.

"The issue with indirect exposure is that it's possible that the compliance screening procedures are not going to see it," Stevenson said.

A web of intermediaries

A complex web of correspondent banking relationships globally means that a single cross-border payment can go through multiple intermediary banks in different jurisdictions before it arrives at its final destination.

The more intermediaries, the more difficult it is for a financial institution to validate the legitimacy of a cross-border payment, according to a 2020 report by the Financial Stability Board. Data provided to meet initial checks may be lacking elements needed for checks under other national regimes, it said.

Weak or inconsistent sanctions supervision across jurisdictions increases the likelihood that correspondent accounts can be exploited to facilitate the flow of illicit proceeds, according to the U.S. 2020 National Strategy on combating terrorist financing.

Correspondent banking has been at the heart of major financial crime schemes, where illicit actors have exploited weak links in the chain to launder money into the European and U.S. financial system.

Danske Bank A/S's Estonian branch, for example, was found in 2018 by an internal probe to have processed up to €200 billion of suspicious nonresident money from 2007 to 2015. Meanwhile, international lenders including JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp. and Deutsche Bank AG reportedly acted as correspondent banks for the branch and helped it to clear dollar transactions.

JPMorgan reportedly terminated ties with Danske Bank Estonia in 2013, while Bank of America and Deutsche Bank followed in 2015. Deutsche received an administrative fine in Germany over reporting failures related to the case, although it was cleared of allegations of aiding and abetting money laundering. U.S. investigations into the case are ongoing.

S&P Global Market Intelligence reached out to JPMorgan, Bank of America, Deutsche Bank and Swift to ask whether correspondent banking is posing a heightened sanctions risk amid the current environment. All declined to comment.

Fines may come

Banks now face a "significant operational burden" to ensure transactions through their correspondent banking ties are compliant, and they will likely be reviewing relationships in light of the conflict, said Woolley.

Correspondent banks could face administrative or financial penalties should they fail to put in place appropriate controls and policies to mitigate the risk, said Woolley, adding that the reputational damage from being involved in any scandal could be detrimental.

Breaching sanctions is a serious offense. French bank BNP Paribas SA paid a record fine of about $9 billion in 2015 after violating U.S. sanctions against Sudan, Iran and Cuba.

Given the complexity of the sanctions against Russia, it is "highly likely" that authorities, including the U.S., will start investigating breaches over time, said Vitaline Yeterian, senior vice president for DBRS Morningstar's global financial institutions group. It is the banks "on the front-line" that face the highest enforcement risk, she said.

As is often the case, it may well take years before any such scandals emerge, said Li.