Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

10 Jan, 2021

By Ranina Sanglap and Rehan Ahmad

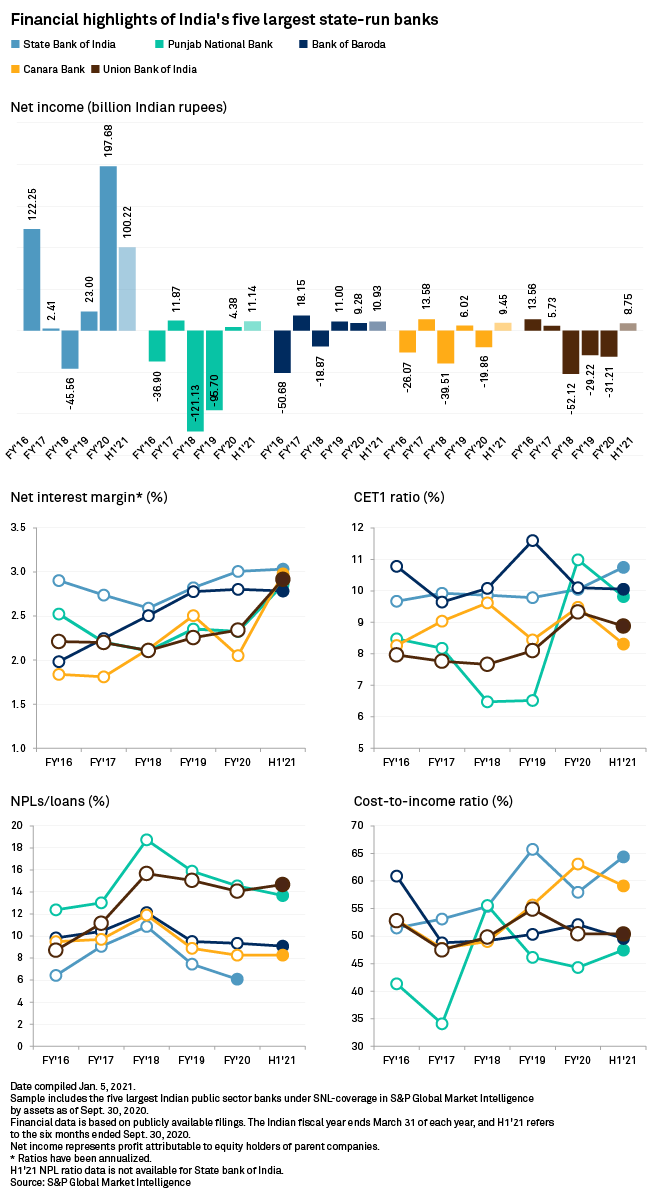

An expected surge in bad loans in India's banking sector this year could hit state-owned lenders harder than their more-nimble private-sector rivals, and they may need to lean on the government for more capital to support credit demand as the economy emerges from a pandemic-induced contraction.

As forbearance measures to help businesses and individuals survive the pandemic end on March 31, analysts expect nonperforming assets to spike later this year. Last year, the industry's NPA ratio enjoyed a brief decline from a recent peak in 2018 as regulators tightened controls and bankruptcy resolutions accelerated. Banks' gross NPA ratio declined to 7.5% at the end of September 2020 from 8.2% at the end of March 2020.

"Public-sector banks in India will likely have trouble maintaining momentum after the amount of new nonperforming loans declined in the [fiscal year] first half to Sept. 30, 2020," said Nikita Anand, the associate director for credit risk in emerging markets at S&P Global Ratings.

State-owned lenders play a dominant role in India's banking sector, with a wide branch network that serves the financial needs of an underbanked population. However, public-sector banks have struggled with bad debts in the last few years that dragged on their profits. The Reserve Bank of India in August allowed one-time loan restructuring for stressed borrowers to soften the impact of COVID-19 that allows lenders to avoid classifying those loans as nonperforming assets.

The central bank said Dec. 29, 2020, that asset quality in the Indian banking system may "deteriorate sharply" due to the uncertainty caused by the pandemic. State-run lenders had higher slippage in asset quality than private-sector and foreign banks,

Somewhat cushioned impact

Ratings expects Indian bank nonperforming loans to rise to between 10% and 11% after forbearance is phased out. However, a stronger-than-expected resumption of economic activity, government credit guarantees for small and medium enterprises, and buoyant liquidity may help limit the stress, Anand said.

Banks will likely see higher delinquencies in retail and small-ticket loans, unlike in recent years when corporate stress was the key contributor to a rise in bad loans, Shibani Sircar Kurian, head of equity research at Kotak Mahindra Asset Management Co., told S&P Global Market Intelligence in an email. State-owned banks typically have a bigger share of that segment of loans.

"The good part is that collection efficiency trends have started showing signs of improvement and many banks, private and public, have made provisions in anticipation of higher delinquencies," Kurian said.

Large public-sector banks have indicated that they expect only a limited restructuring of loans, according to local media reports. State Bank of India expects less than 1% of its loans to be restructured. Others, such as Union Bank of India and Punjab National Bank, expect restructuring to be below 3% of their loan books as borrowers emerge from the crisis in better shape than previously expected.

Ratings expects between 3% and 8% of the loans to be restructured. However, "corporate earnings have strongly recovered after the COVID shock, and we do not expect any large corporate debt restructuring. At this juncture, we believe the system restructuring could be at lower end of our estimates," Anand said.

India's economy appears to have bounced back faster than initially expected as the government scaled back from one of the strictest lockdowns in the world to contain the spread of the virus. While India slipped into its first technical recession on record in the July-to-September quarter, the economy contracted 7.5% for the period, compared with a 23.9% plunge in the previous three months.

Various indicators of economic recovery, including proprietary indexes compiled by Nomura and Jefferies, have reflected improvement after new COVID-19 cases showed a declining trend from a September peak. India's National Statistics Office estimates that the GDP will contract by 7.7% in the year that ends on March 31 amid a broad-based "resurgence of economic activity."

Need for capital

As economic growth picks up, banks will need to have more capital to support that expansion. "We expect government-owned banks as a whole should be able to absorb our estimated credit losses without breaching the regulatory minimums. However, these banks are generally less capitalized than private-sector peers, and need capital to grow," Anand said.

State-owned banks will need 300 billion rupees to 400 billion rupees in capital in the next 12 to 18 months to support credit growth, she added.

"The larger private [sector] banks should not face much challenges on this front but many of the public-sector banks and some of the smaller private-sector banks may find the going tough," said Krishnan Sitaraman, senior director at CRISIL, a unit of S&P Global.

State-owned banks largely rely on the government for capital infusion. In 2019 to 2020, the government proposed to infuse 700 billion rupees into government-owned banks to boost credit, taking the total to 3.16 trillion rupees in the last five years. In the current fiscal year, the government has earmarked 200 billion rupees for capital infusion into the state-owned banks, in addition to the lenders' capital raising from other sources.

For example, State Bank of India issued 40 billion rupees of Tier 1 capital notes in July last year as part of a 140 billion rupees capital offering in two tranches. The overall amount raised by public-sector banks via qualified institutional placements and bond issuance doubled in the year that ended March 2020 over the previous year. Between April and November 2020, the amount raised via private placements had surpassed the previous year's figure, according to the RBI. However, depressed valuations have led public-sector banks to largely abstain from public issuances, it noted.

Still, public-sector banks may continue to lose ground to their private-sector rivals. Their market share has declined to 59.8% in 2020, from the over 70% in 2015, according to data from the RBI. Private-sector banks' market share increased to 36.04% from 21.26% over the period.

"Incrementally, in order to regain some of their lost market share, public-sector banks need to focus on improving their core profitability metrics and strengthen their balance sheets," Kurian said.

An improvement in their return on assets "would enable state-owned banks to raise capital directly from the markets rather than rely on their promoters for capital infusion," she said.

As of Jan. 8, US$1 was equivalent to 73.32 Indian rupees.