Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

20 Apr, 2021

By Sanne Wass and Rehan Ahmad

The greener investment strategies of Nordic banks' asset management units compared with their lending businesses underscores a sustainability gap that lenders will want to close to meet their climate targets and to manage reputational risk.

As investors, analysts, regulators and the public increasingly prioritize environmental, social and governance issues, major Nordic banks have signed up to the Principles for Responsible Banking and have committed to bringing their financing in line with the Paris Agreement on climate change, which among other things requires carbon dioxide emissions to reach "net zero" by 2050.

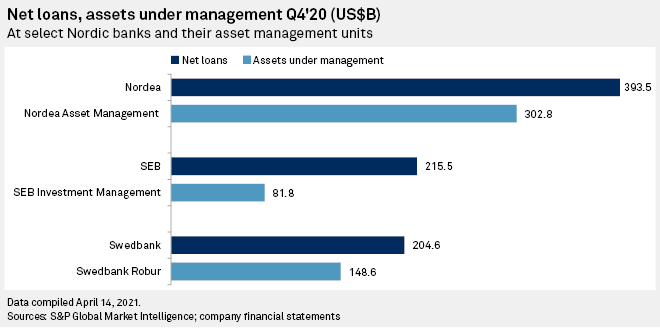

In a wave of announcements in the first quarter of 2021, Sweden's SEB Investment Management AB said it will start blacklisting fossil-fuel assets across its investment funds, while Swedbank Robur AB will only invest in oil and gas companies that are on its "Green List." Nordea Asset Management has restricted the majority of its funds from holding oil and gas stocks that are not aligned with the Paris Agreement, and claims its wealth and asset management business will likely be "100% ESG" in five to 10 years.

Meanwhile on the banking side, sustainability ambitions are lagging. "Within lending we only see marginal improvements and the policies are written in a way that financial support to existing fossil fuel clients will not really be stopped," Jakob König, advisor at Fair Finance Guide Sweden, told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

This sustainability gap is a trend across the Nordics, according to recent research by BankTrack, Fair Finance Guide Sweden and other environmental organizations. Analyzing the fossil fuel policies and financing of the 10 largest banks in Sweden, Denmark and Norway, including also Finland-headquartered Nordea Bank Abp, the research found that asset management units have "often adopted stricter policies."

"The lending side is much more important to address," König said. "If you're an investor, you're one of thousands of shareholders. If you're a creditor, you are one of much fewer that are enabling the company to finance its activities. It's a much more active support."

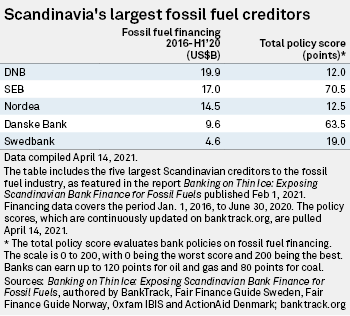

Scandinavian banks have provided substantial financing to the fossil fuel industry — at least $67.3 billion since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, according to the research, which studied loans issued from 2016 until mid-2020.

All 10 lenders covered by the research are signatories to the Principles for Responsible Banking. Yet the research found that Scandinavian banks have made little progress in decreasing their fossil fuel support in the last five years, with financial flows to oil and gas remaining stable over the period.

'More advanced'

As for banks' fossil fuel lending policies, BankTrack, which continuously updates its assessments, labels eight of 10 of the Scandinavian lenders as "laggards." DNB ASA and Nordea, the largest and third-largest creditors to the fossil fuel industry, along with Swedbank AB (publ) are included under this label.

|

Although Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB (publ) and Danske Bank A/S score higher and are labeled "followers," their policies contain "major loopholes," Daisy Termorshuizen, climate campaigner at BankTrack, said in an interview.

SEB, for example, still makes an exception to its commitments regarding coal for German companies.

None of the banks' policies require them to cut off lending to fossil fuel companies that do not have a credible transition plan in line with the Paris Agreement, said König.

Nordic banks are generally "much more advanced" on ESG when it comes to funds and financial products offered through their asset management units, according to Mario De Cicco, vice president for global financial institutions at DBRS Morningstar. Banks are likely finding it easier to structure and sell green investment products and are supported by investor demand, he said in an interview.

Sustainable investment fund inflows reached record levels in 2020 and have generally outperformed the market, while recent research found that poor ESG practices are associated with lower risk-adjusted stock returns.

The environmental risk associated with fossil fuel companies is "being priced into the equity market," meaning that holding stocks in such companies is "already a bit uncomfortable," König said.

On the lending side, the financial risk is less tangible at present, and as a result it would be more costly for banks to end banking relationships with fossil fuel clients, he said.

"It's still very profitable for the banks [to finance fossil fuels]," König said, adding that a bank loan usually runs for five years, a shorter time frame than the risk of bankruptcy for those companies that might be left behind in the energy transition.

Banks, meanwhile, defend the continued financing of polluting companies.

"Fossil fuels still play a major role in society in facilitating a controlled transition and will do so for a fairly long period of time. The most important thing we can do is stay involved and finance the necessary transition," said Fredrik Nilzén, Swedbank's head of sustainability, in an email.

SEB said in an email that it has long-time clients with fossil fuel operations and it "feels a responsibility to support these companies in meeting the Paris Agreement through an orderly transition."

Short-term risk

While energy transition largely remains a long-term risk, financing the fossil fuel industry today is not unproblematic. Reputational damage is the immediate risk, while in the medium term, climate-related risk could impact capital requirements that regulators set, said Vitaline Yeterian, senior vice president for DBRS Morningstar's global financial institutions group.

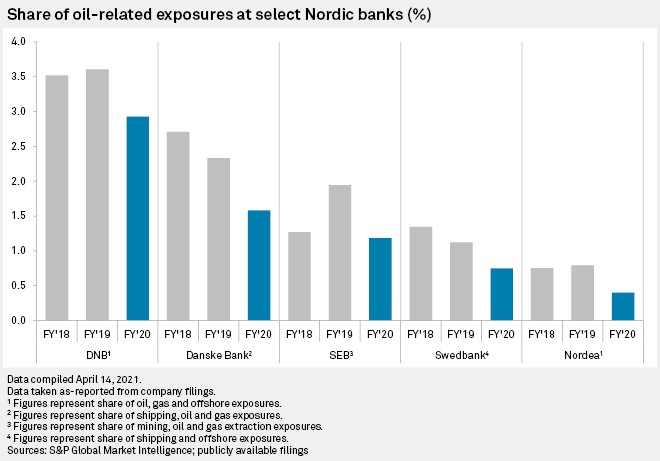

Credit analysts are optimistic that Nordic banks' portfolios are becoming more sustainable, albeit at a slower pace than their asset management units. In a positive development, De Cicco noted that banks reduced their overall exposure to oil-related sectors significantly in 2020.

Investors are not only interested in what banks exclude, but also "how they work with what they have," said Pierre-Brice Béguinet-Hellsing, an analyst in S&P Global Ratings' sustainable finance team.

"Beyond exclusion policies, it's important ... to understand how ESG risk is factored in underwriting processes and investment decisions and not least how engagement is being done with existing exposures," Béguinet-Hellsing said. On this point, Nordic banks through their annual sustainability reports are generally detailed and transparent about their ESG policy framework and, in his view, currently have "extensive policies."