Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

19 Jul, 2021

|

| A floating wind farm being built off the coast of Portugal. The sector is ready to deliver commercial projects, industry insiders say. Source: EDPR |

As floating wind expands from just small-scale pilots to commercial projects, pioneers of the technology will still need years to turn proof-of-concept into a competitive industry.

Portugal's EDP Renováveis SA, which is developing offshore wind with Engie SA through their Ocean Winds SL joint venture, is among the European utility first-movers in the floating space.

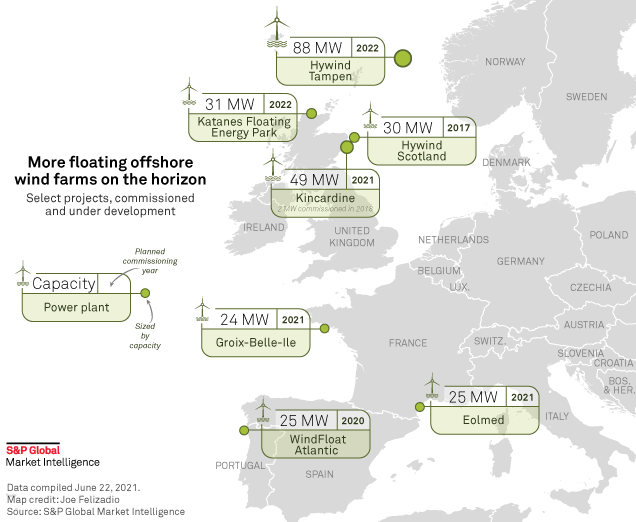

"There are a few floating technologies that are mature. What we need now is industrialization," said José Pinheiro, project director of the 25-MW WindFloat Atlantic wind farm, EDPR's first floating project, commissioned in late 2020.

Industrialization will help bring costs down. And the kind of cost reductions that took a decade in traditional fixed-bottom offshore wind "will likely go faster in floating," said Geir Olav Berg, chief technology officer at developer Aker Offshore Wind AS.

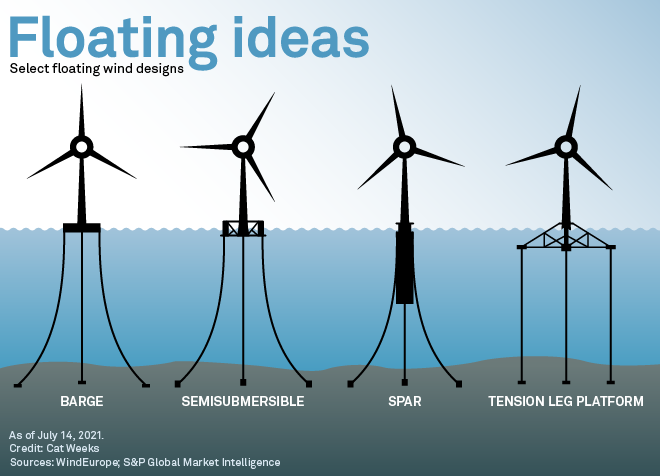

One issue is that the market has not yet settled on which floating technology designs are most promising, which some say is hampering faster scale. "Having many different designs at different levels of maturity is not helping the industry to go as fast as we all wanted," Pinheiro said.

EDPR's WindFloat Atlantic project was developed with technology-maker Principle Power Inc., one of the market leaders with a semisubmersible foundation design. "A cost advantage is that the semisubmersible substructure does not scale with the turbine. ... The cost per megawatt will actually go down as the turbine gets larger," Berg said in an email. Aker Offshore Wind has a stake in Principle Power and uses the technology in its projects.

EDPR is open to different designs. "We want to draw from the market like we draw from the wind-turbine suppliers, not only from a technical point of view but also from a financial perspective," Pinheiro said in an interview.

Cost curve pointing down

Up to 70% of floating wind's costs are the same as in fixed-bottom projects, Berg said. "Hence, we direct our attention on reducing the 30-40% of the cost elements that are different: the substructures, mooring, dynamic cables, and marine operations and installation."

Equinor ASA, another Norwegian player with a history in the North Sea's oil and gas industry, operates the 30-MW Hywind Scotland project and is building its larger sister site, the 88-MW Hywind Tampen, in Norway.

Between Equinor's first floating wind pilot and Hywind Scotland, capital expenditure per megawatt dropped by 70%, according to the company. It now expects a further 40% drop by the time Hywind Tampen is commissioned in 2022. "It's becoming a scale which is not a pilot any longer; it's a producing asset," Sonja Chirico Indrebø, the company's head of floating wind, said in an interview.

To scale up deployment, the industry will also need access to ports in Europe that are big enough and deep enough to house and construct the large floating structures. "We need to bring more capable ports into play that will allow bigger projects to be constructed in a fluent manner," Pinheiro said.

Meanwhile, given that only a few projects are online, lessons on maintenance of floating wind farms are still being learned, according to Espen Bjørnson, a ship broker specializing in offshore renewables at Clarksons Platou. "The further offshore you go, the more complex the operations become," Bjørnson said in an interview.

Regulatory boost needed

As the technology develops, floating wind still relies heavily on political will and regulatory support. Trade group WindEurope expects as much as 7 GW of floating capacity in Europe by 2030, with the U.K. aiming for 1 GW of floating wind by then, and Spain targeting 1 GW to 3 GW. The EU is shooting for 300 GW of offshore wind, including both floating and fixed bottom, by 2050.

Floating cannot yet compete with fixed-bottom offshore wind on cost, making technology-specific auctions for subsidy support necessary, according to Chirico Indrebø. Using France's South Brittany renewables auction as a positive example, EDPR's Pinheiro said initial floating wind auctions need "realistic targets" with small-to-medium capacity scope in the 250 MW to 300 MW range.

Beyond that, regulators ought to consider entry criteria beyond simple local content requirements, looking at company track records in deploying renewables. "In these first years these criteria are important so that reliable players are coming in and deploying the quantity of power that is needed," Pinheiro said.

Chirico Indrebø also pointed to seabed availability. "We need acreage, we need access to areas to develop," she said. While sites further offshore are unlikely to upset seaside communities, they often share space with industries like fishing and defense.

As market interest in floating wind grows and regulation helps the technology scale up, its proponents think it could end up being the most cost-effective option offshore in the longer term. "Their thesis is that at scale they can become cheaper than fixed-bottom," Bjørnson said of the floating wind sector. "It's really kicking off now."