Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

29 Oct, 2021

|

| A climate change mural on a wall near the COP26 venue in Glasgow, Scotland. Source: Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images News via Getty Images |

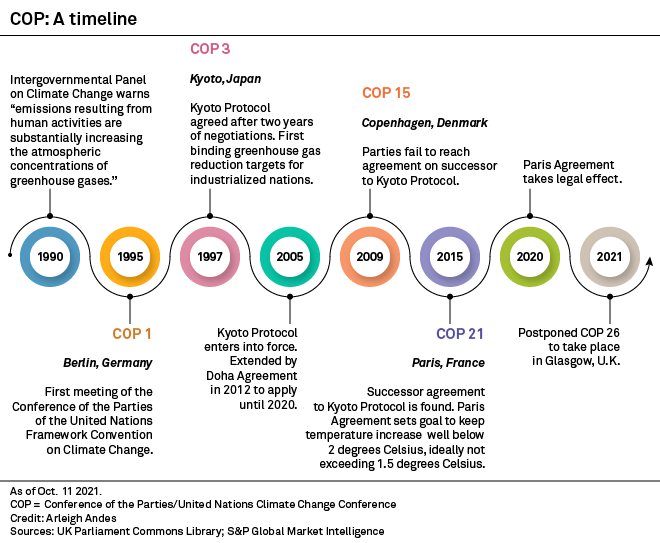

The COP26 climate summit, which kicks off in Glasgow, Scotland, on Oct. 31, marks another attempt to tie up a crucial loose end from the Paris Agreement on climate change: the creation of a global carbon market.

Negotiators need to agree on rules around emissions transparency and registration under a framework set out in Article 6 of the 2015 Paris accord, the landmark agreement designed to help limit global warning to 1.5 degrees C. The article would also prevent two countries separately claiming the same emissions reductions and create a United Nations mechanism certifying carbon credits that governments can use to offset emissions.

Article 6 is yet to be implemented, even with discussion at every COP since Paris, partly because of disagreement over whether countries should be able to include their unsold carbon credits in a new global trading system.

Addressing such sticking points would enable economies to leverage emissions trading for their net-zero goals, which may be strengthened if talks in Glasgow succeed, while improving accountability for polluting industries and countries. An agreement could help generate as much as $1 trillion per year by 2050 in support of climate targets, according to an Oct. 26 International Emissions Trading Association report.

"What difference does it make if you pledge something at a high level if the accounting and reporting is not accurate," Kevin Conrad, a climate negotiator for Papua New Guinea, said in an interview. "It makes a total disconnect."

Article 6 would bolster the market for voluntary carbon offsets, used by companies to offset emissions, and unleash a wave of investment and liquidity in a market that is tipped to grow by a factor of at least 15 by 2030, according to the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets.

An agreement on the issue in Glasgow is essential in holding polluters accountable under a global system and strengthening emissions reductions over time, said Conrad, who is also executive director of the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, a climate advocacy group representing more than 50 nations. Companies, cities, states and countries should all become part of the global accounting system, he said.

"The voluntary markets aren't even close to that kind of ambition, that kind of robustness," Conrad said.

A global price on carbon

Once Article 6 is finalized, attention would turn to trying to negotiate a global price of carbon. Reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 would require a price of $100 per tonne of CO2, according to a Reuters poll of climate economists, incentivizing the switch to renewables.

But like with other climate issues, reaching a consensus on a carbon price will not be easy. "I am not personally optimistic about an internationally agreed carbon price; there have been no real breakthroughs," said Faustine Delasalle, co-executive director of climate group Mission Possible, which works on climate action with 300 companies in industrial sectors that are difficult to decarbonize.

Industrial sectors are most impacted by carbon pricing regimes and also face strong international competition, Delasalle said, especially if production can be shifted to jurisdictions where pollution is cheaper or not priced at all, an effect called carbon leakage.

Delasalle sees movement at a national level, with countries developing new approaches to carbon pricing. "The fact that the EU is speaking openly about a carbon border is a major breakthrough," she said in an Oct. 12 interview.

Sectors like steel and chemicals, which are harder and costlier to decarbonize, are not yet at the forefront of COP negotiations and often not even featured in countries' Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs, despite representing about one-third of global emissions, Delasalle said. "Governments reach to the lowest-hanging fruits."

Calls for nearer-term targets

Implementing Article 6 successfully would allow nations to leverage carbon markets in their quest for net-zero. Economies like the U.S. and U.K., as well as the EU, have among the most ambitious emissions-reduction goals in place.

"[The targets] are going to require very radical measures in all of those countries," Peter Betts, a former U.K. and EU climate negotiator, said in an interview. "There are going to be moments ... where there are real crunches, where the policy really starts to bite."

One of the chief goals of the Glasgow talks is a strengthening of countries' NDCs. While many economies now have ambitions to be carbon neutral by 2050 or 2060, not all of them have interim goals that would help improve visibility for businesses.

"If you had 2050 profit targets and you presented them to analysts, they would say, 'That's all very interesting but show me what you're doing in the next four quarters,'" John Browne, former CEO of oil major BP PLC, said at the BNEF Summit in London on Oct. 18 about the need for interim targets.

The adoption of nearer-term goals would help avoid delaying climate action, according to Benito Müller, convener of international climate policy research at the University of Oxford's Environmental Change Institute.

If countries just have a long-term net-zero target, there is a "tremendous" temptation to procrastinate, Müller said in an interview. Having regular interim targets and assessments "is very important to avoid that," he said.

While strengthened commitments from the big emitters might prove to be one success from Glasgow, issues like Article 6 remain at the behest of the COP's format of consensus-based negotiation.

"Everything is consensus," Betts said. "In a way it's remarkable how much has been achieved [through the COP process] so far."