Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

11 Oct, 2021

The takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban has raised questions about the future of modern banking in the war-torn nation after two decades of progress under the previous U.S.-backed government.

The new regime has ordered banks to reopen, with some restrictions, as it seeks to restart normal life and gain legitimacy. It also appointed an acting governor for the central bank, who has sought to assure people that banking operations will continue as normal.

Under the new acting governor, Da Afghanistan Bank, or DAB, capped individual withdrawals at $200 or 20,000 Afghani per week and $25,000 per month for businesses after thousands of customers lined up in front of bank branches to withdraw cash. Lending activities are suspended as banks tread with caution amid the uncertainty.

"The private banks are barely having enough physical cash to entertain customers' withdrawal requests for another month without liquidity support from the central bank," M. Naweed Yosofi, deputy chief risk officer of Kabul-headquartered private lender Azizi Bank, told S&P Global Market Intelligence. "The banks are receiving their partial balances from their current and saving accounts with [the] DAB, albeit need-based, to continue running their operations."

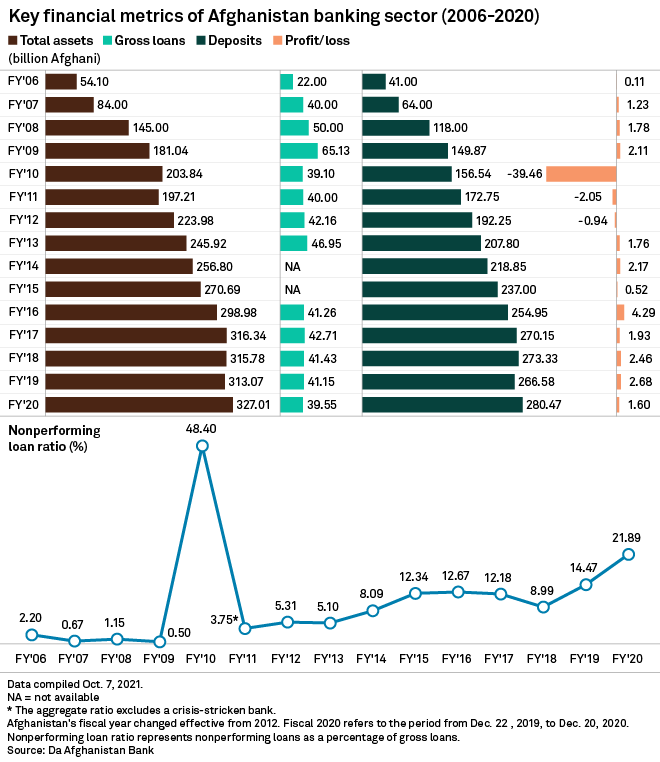

When the Taliban were ousted in 2001, Afghanistan was left without a functioning banking sector, though several financial institutions had a banking license and a roster of staff on their payrolls, according to the International Monetary Fund. Since then, Afghanistan's banking sector has grown to comprise 12 commercial lenders, including three that are state-owned and seven in the private sector. Total assets in the banking system stood at 327.01 billion Afghani, deposits totaled 280.47 billion Afghani and gross loans were 39.55 billion Afghani as of end-2020, according to DAB data. Private-sector banks accounted for 67.4% of total banking sector assets, while state-owned banks held a 26.9% share.

Interbank deals inside Afghanistan and outside the country using SWIFT, the international financial messaging platform, are not possible because SWIFT is currently out of operation, Yosofi said, adding that without additional support from the central bank, banks could soon run out of cash. Previously, the DAB used to conduct market operations, setting the value of the Afghani and controlling inflation, through auctioning U.S. dollars.

Lenders, heavily reliant on a steady inflow of dollars before the withdrawal of the U.S. troops and Taliban takeover in August, may see their liquidity dry up if aggressive deposit withdrawals continue. Only 15% of the population has access to banking services and the economy is largely cash-based.

The country's banking system shut completely for a few weeks after the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan on Aug. 15. Further exacerbating the situation, the U.S. cut off the Afghanistan central bank's access to its more than $7 billion of assets, and the IMF suspended the country's access to over $370 million of funds. Others, including the World Bank and Germany, followed suit, leaving the new regime with limited space to run a functioning banking system. Germany was one of the biggest foreign donors to Afghanistan and provided $409 million in grants in 2019, according to data from The Donor Tracker.

"The situation raises the prospect of a severe economic and humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan as the country's banks cannot be self-sustained without any support from the central bank," said Abdul Samad Katawazy, an adviser to the previous Afghan government. In most cases, customers are allowed to withdraw funds only in the local currency, Canada-based Katawazy said.

What may help is that Afghanistan banks' ratio of liquid assets to short-term liabilities stands at around 85%, said Syed Masroor Hussain Zaidi, research analyst at Pakistan's Foundation Securities. As a largely cash-based economy, the analyst said the overall reliance on the banking system has been low. Currency in circulation makes up around 50% of the country's M2, a measure of money supply that includes cash and liquid instruments, which is significantly higher than its neighbors, Zaidi said, adding that this "dilutes the quantum of this problem."

In neighboring Pakistan, for example, currency in circulation accounted for 28.5% of M2 as of June 30, according to data from the State Bank of Pakistan.

Zaidi, however, warned that Afghanistan lenders could see a further uptick in their nonperforming loans. NPLs swelled to nearly 22% of total loans in 2020 from 15% in 2019, according to the central bank.

The central bank's acting governor, Mohammad Idrees, said Sept. 15 that Afghanistan banks, on average, keep 50% of their capital with them in cash, in local and foreign currencies, and that "banks are completely secure" and "the banking sector is in a good condition."

"Commercial banks are conducting their activities in accordance with the procedures … and will soon return to normal," Idrees added. "All commercial banks operating in the country are under serious supervision and are conducting their operations better than before."

The central bank did not respond to an email from Market Intelligence seeking comments on the potential crisis facing the lenders.

As of Oct. 8, US$1 was equivalent to 90.71 Afghani.