Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Blog — 24 Nov, 2020

When California utility Pacific Gas and Electric filed for Chapter 11 protection in 2019 after facing enormous liabilities from wildfires, the Wall Street Journal dubbed it “the first climate-change bankruptcy.”[1] As the varying impacts of climate change and the importance of mitigation become more widely known, the financial risks and implications of inaction by some companies has come to the forefront.

The power generating sector has been one of the earliest and fastest to decarbonize, yet not all companies within the sector have taken action. This makes power generation an interesting example to see which companies could potentially win from a carbon transition — and which could be left behind. Companies greening their generation today are best poised to do well under multiple climate transition scenarios.

The Climate Credit Analytics tool

S&P Global Market Intelligence and Oliver Wyman’s[2] new Climate Credit Analytics makes it easy to assess counterparty risk from the transition to a low-carbon economy, and offers in-depth company-level analysis. The solution leverages relevant company financials and industry-specific data — such as electricity generation mix, regulation status, and operating costs — to enable a bottom-up modeling approach. The tool lets users assess potential changes in counterparty credit scores[3] and probabilities of default across a range of both orderly and disruptive climate transition scenarios.

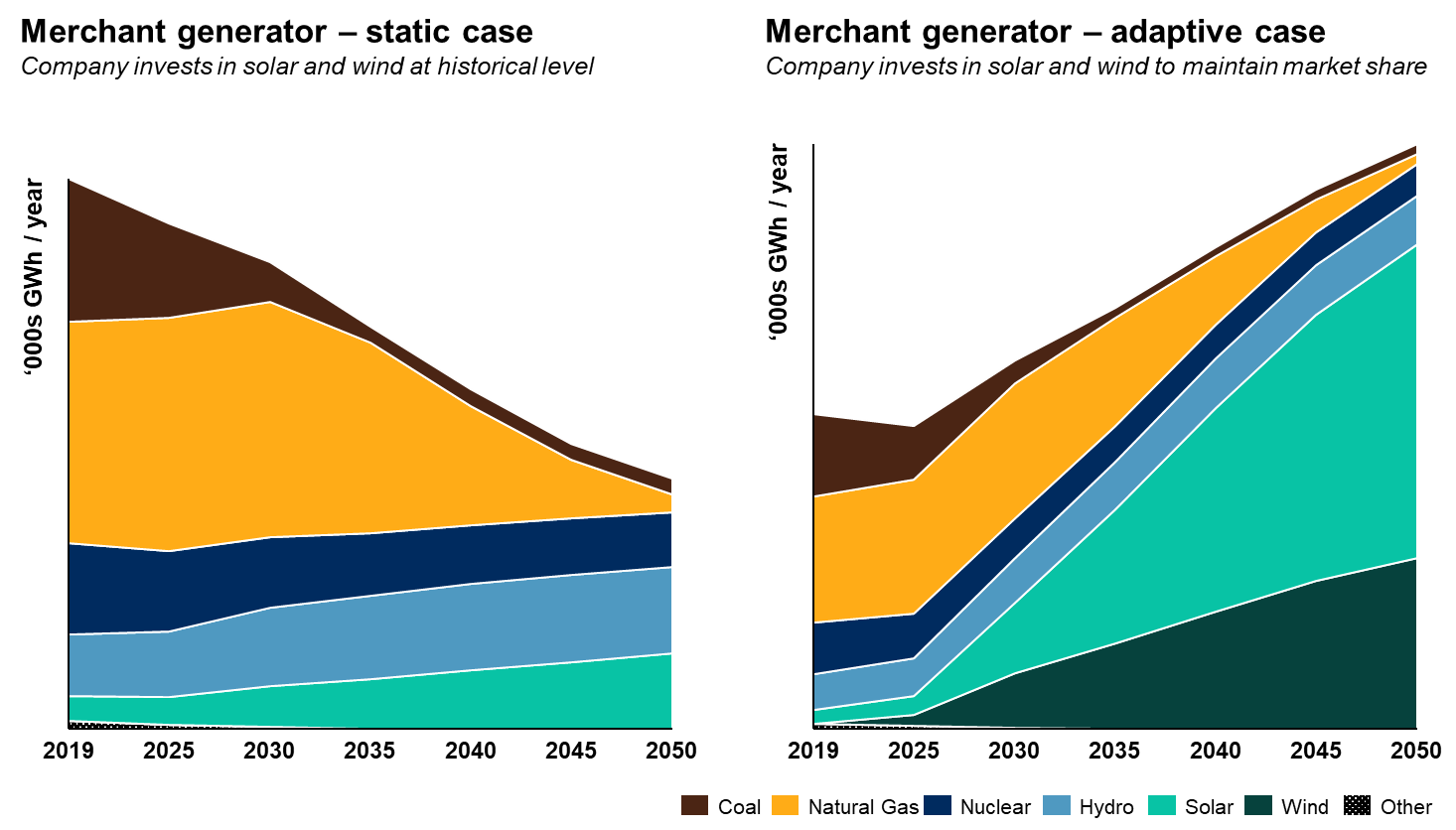

The power generation module also enables users to assess the impact of a given counterparty’s adaptive response. In the static approach, firms invest in renewables at their historical rate, locking in their current investment priorities. In the adaptive approach, firms invest in renewables in a manner that maintains their current market share of generation in an increasingly green landscape.

A sample transition scenario

These investment patterns offer two plausible impact pathways and can be used to explore the range of potential outcomes for an individual firm. In the example shown in Figure 1, a merchant generator’s coal plants become less economic to run and generate less under both approaches. Coal-to-gas switching protects revenues in the short term, but natural gas generation begins to fall by 2030 as these plants begin to be displaced by less expensive renewable generation. In the static case, the firm chooses not to invest. As a result, its electricity production starts to drop, leading to a decline in market share and diminishing revenues. In the adaptive case, the firm makes considerable capital investments in greener technologies, such as solar and wind, in order to increase production and revenues.

Figure 1. Volume generated over time for a merchant generator in the static and adaptive cases under 2°C with carbon dioxide removal scenario

Other includes oil, biomass, and geothermal

Source: Climate Credit Analytics analysis, as of November 21, 2020. For illustrative purposes only.

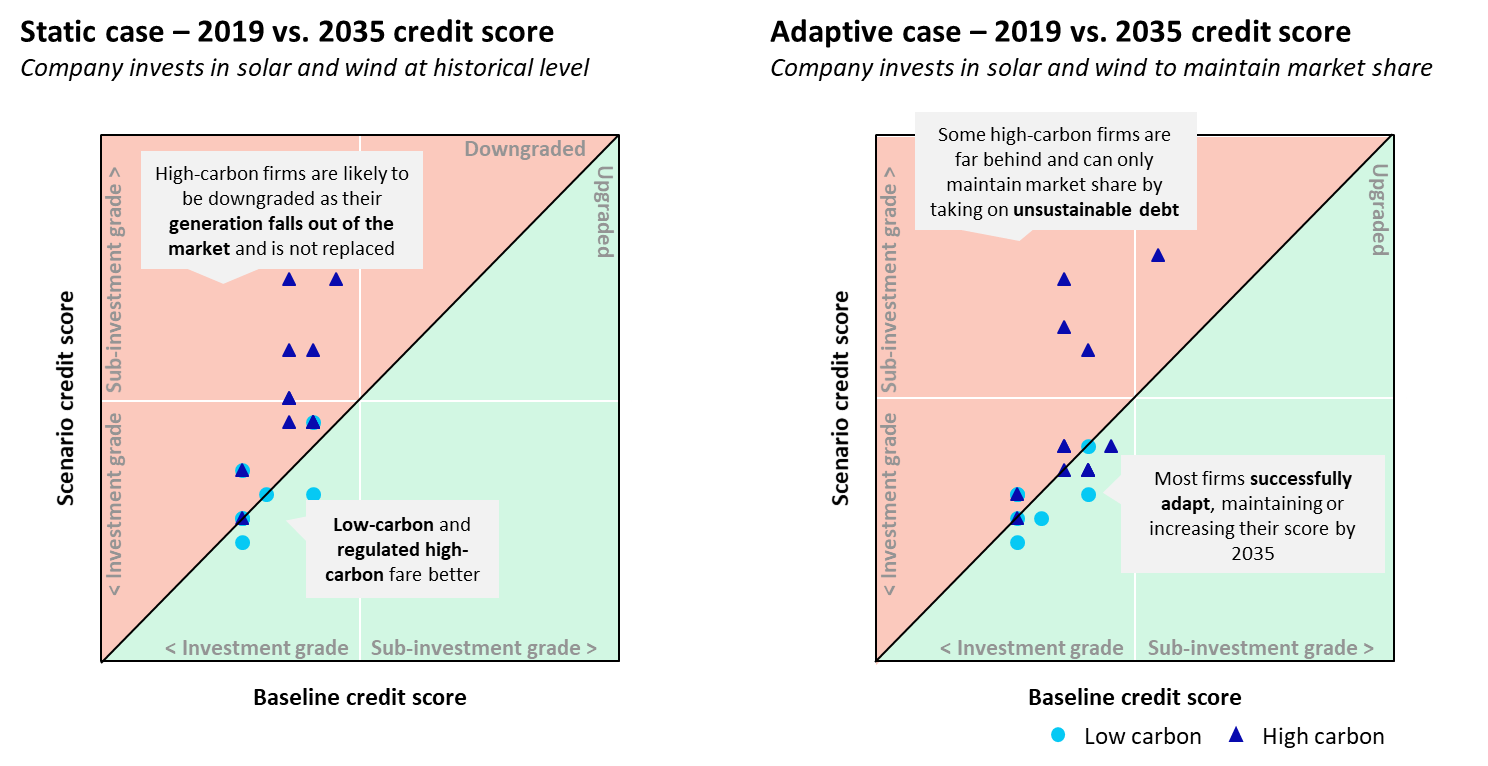

Figure 2 shows the impact of these investment decisions across several firms in the industry. How well a firm performs depends on its: regulation status, baseline generation carbon intensity, and baseline financial position. Firms with more unregulated capacity, carbon-intensive production, or high debt tend to perform worse than others as the sector decarbonizes.

Figure 2. Credit risk analysis: change in credit score from 2019 to 2035 under 2°C with carbon dioxide removal scenario, where ‘high carbon’ refers to firms with 50% or more of their baseline nameplate capacity in coal and gas plants.

Source: Climate Credit Analytics analysis, as of November 21, 2020. For illustrative purposes only.

As the power generation sector moves forward with decarbonization, there is a growing need to evaluate the credit risk impact of climate transition pathways. Climate Credit Analytics is a comprehensive tool that enables users to quickly compare firms across a range of transition pathways, making it easy to see which firms are well positioned to thrive.

Co-authored by:

1. Alban Pyanet, Partner, Oliver Wyman’s Risk and Public Policy. Alban supports banks, insurers, and investors to better manage their exposure to climate change, through climate stress testing and broad integration of climate-related considerations into risk management processes.

2. Becky Kreutter Swanson, Consultant, Oliver Wyman. Becky joined Oliver Wyman after working in government on climate, resilience, and building and land use policy, including at the NYC Mayor's Office of Resilience and White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Becky holds a Master in Public Affairs and BA from Princeton University.

[1] See WSJ Jan. 18, 2019, “PG&E: The First Climate-Change Bankruptcy, Probably Not the Last”: https://www.wsj.com/articles/pg-e-wildfires-and-the-first-climate-change-bankruptcy-11547820006

[2] Oliver Wyman is not affiliated with S&P Global or any of its divisions.

[3] S&P Global Ratings does not contribute to or participate in the creation of credit scores generated by S&P Global Market Intelligence. Lowercase nomenclature is used to differentiate S&P Global Market Intelligence credit model scores from the credit ratings issued by S&P Global Ratings.

Blog Article