Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Blog — 27 May, 2024

By Byron McKinney and Yingzhi Zhang

A recent report in local Chinese media outlets reported that an importer received 100,000 metric tons of oil product via tanker Borey G (IMO: 9199127) arriving at Qingdao, mainland China, in October 2023[1]. The cargo was declared as "other fuel oil" under HS Code 2710.19.29; however, it turned out to be utilized for refining purposes, therefore, implying a shipment of crude oil that should technically be reported under HS 2709. Mainland China customs data shows that in October 2023, the import volume under "other fuel oil" HS code 2710.19.29 exceeded its full-year volume in 2022. Additionally, the value of mainland China’s oil imports classified under the HS Code 2710.19.29 increased by $2.6 billion in 2023.

In this context, it is important that the classification of petroleum products is done with care, ordinarily for local tax and customs regulation but also in respect to the G7 oil price cap policy for crude oil and petroleum products. Crude oil within the price cap policy falls under HS codes beginning 2709.00. Petroleum products fall under the premium-to-crude and discount-to-crude categories within the HS codes of 2710. In the case of oil on board Borey G, the HS Code 2710.19.29 is not covered directly in the documentation issued by the price cap policy. For oil cargoes classified at the tariff level (eight digits in this case), there is a possibility of using a HS code from a particular jurisdiction, although this tariff code may differ from those used by price cap coalition members or in its documentation.

From a trade compliance perspective, there is an additional factor to be reminded of in respect to understanding whether a cargo falls under the price cap or not. An organization determining "safe harbor" (oil cargo priced at or below the cap) needs to understand if the cargo follows the accepted recordkeeping and attestation process. Part of this process covers a requirement to retain documents highlighting that the oil cargo was shipped within the price cap’s parameters. Alongside this type of check is the need to match HS codes to those on the list of covered articles falling under the price cap. A simple matching of HS codes or tariff codes in trade documents to the covered articles in the price cap is not sufficient, as certain local tariff codes will not match and go undetected. The HS/tariff code of 2710.19.29 is one such example. The HS/ tariff code is one method of determination for potential Russian-origin oil, but other factors also play a major role; an understanding of the vessels port of load, route diversions and cargo transfers, oil storage facilities and the ultimate owner of ship and cargo.

Using the example of Borey G, the trade documentation associated with its cargo and the tracking of the vessel's movements highlight potential discrepancies in the journey that can inform trade compliance teams of heightened risk and possible oil price cap evasion.

The recent US Quint Seal Compliance Note outlining "Know Your Cargo" principles (December 2023), the Price Cap Coalition Enforcement Alert (February 2024) and OFAC’s Updated Guidance on Price Cap Policy (December 2023) reiterate several compliance issues potentially present in the Borey G case:

These key compliance elements will be explored in this paper to understand how potential risk can be identified and how using appropriate information as part of a wider risk and compliance screening tool can help to mitigate the identified risks.

Key takeaways

Analysis

Key findings of the Borey G

To determine how various crude oil and petroleum product cargoes are reported with customs and shipped from their load to discharge port, it is important to analyze sources from customs, government statistical authorities, and ship tracking and data services.

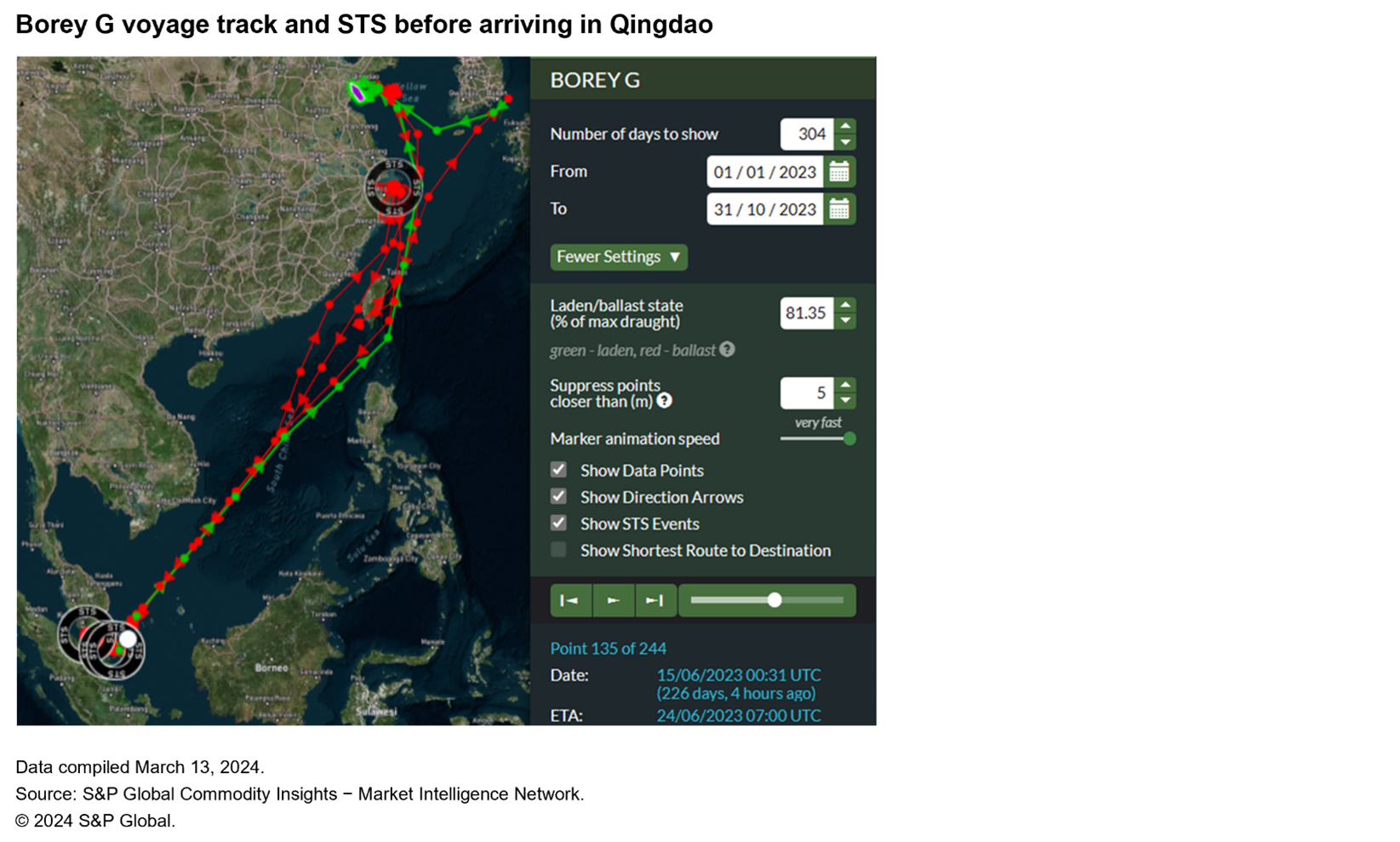

Since the beginning of 2023, the voyage history of Borey G has identified a number of sailing routes between Southeast Asia and mainland China coastal ports, with multiple STS activities taking place near Malaysia. A detailed look at these STS activities identifies four cargo transfers all located near Malaysia with crude oil tankers MS Enola and FSO SA Europe, twice respectively.

Click here to download the full complimentary paper where we will cover:

Subscribe to our complimentary Global Risk & Maritime quarterly newsletter for the latest insight and opinion on trends shaping the compliance and shipping industry from trusted experts.

[1] See Sina Finance, "An importer received 100,000 tonnes of oil product via Borey G vessel, Jan. 20, 2024," https://cj.sina.com.cn/articles/view/6248544856/174713a580200181ig?finpagefr=p_104.

Blog

Research Analysis