Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Blog — 4 Apr, 2023

This blog is written and published by S&P Global Market Intelligence, a division independent from S&P Global Ratings. Lowercase nomenclature is used to differentiate S&P Global Market Intelligence credit scores from the credit ratings issued by S&P Global Ratings.

Something borrowed

In the past few weeks, the U.S. Federal Reserve’s discount window lending facility[1] has increased significantly, shooting up to levels far surpassing those seen even during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. This is indicative of liquidity concerns amongst commercial banks, specifically the community banks that make up the facility’s main user base. This has been epitomized in the recent Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) collapse.

Something old

Indeed, U.S. commercial banks’ balance sheets rose by circa $5tn (U.S.) between 2020 and 2022, on the back of monetary and fiscal stimulus packages deployed as part of the pandemic response efforts. Many banks opted to redeploy their capital into low-yield and, hence, expensive government bonds – thus setting themselves up for an impact from interest rate (IR) risk if the Fed ever tightened monetary policy. What is worse, the 2019 Final Rule on Regulatory Capital and Liquidity Requirements excluded community banks and imposed very relaxed liquidity and other regulatory requirements on smaller banks, like SVB, with total assets less than $250bn.

In this sense, the issue behind SVB’s collapse was not whether they held their bonds in their trading or investment book but, rather, that the bank was forced to honour its deposit liabilities after the Federal Reserve had ended the benign credit cycle, forcing the bank to sell the bonds at a loss.

Something new

In response to these concerns, the Federal Reserve recently introduced the new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) that accepts collateral at par – without any haircut. The BTFP, and effective supercharging of FDIC guarantees in the case of SVB, may be enough to limit fallout or – in the absence of a free lunch – buy some time.

Banking blues

Still, some regional U.S. banks will likely see further credit risk deterioration. A research paper published by S&P Global Market Intelligence in October 2020 lists the 20 largest U.S. banks by unused commitments and gross loans and leases. This was marked as a potential red flag “given perceptions of 'buying' loans or stretching on credit”, particularly as deposit outflow intensified and ratios deteriorated as a result.

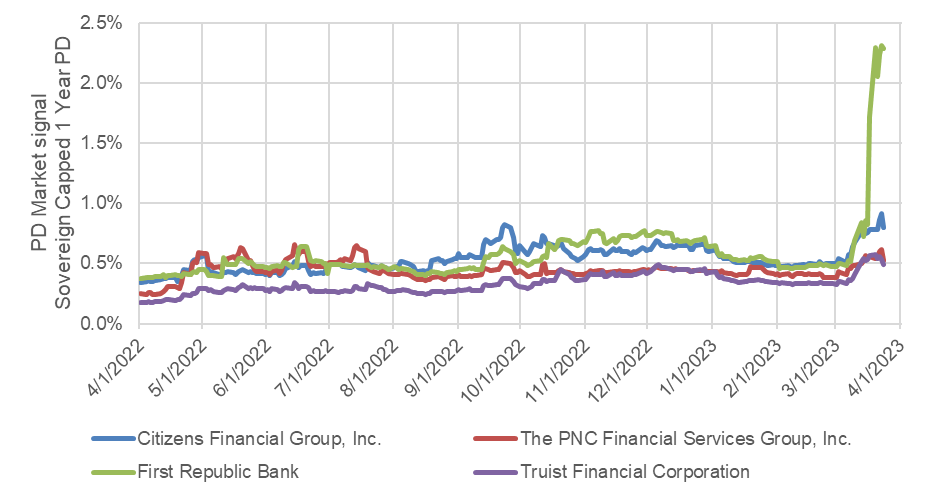

Credit Analytics’ PD Model Market Signals v2.0 (PDMS v2.0) identified four U.S. banks that were flashing amber, or even red, in the credit risk statistical models all the way back in mid-2022, based on the following criteria:

All four saw a significant balance sheet expansion since 2020 and a large build-up of deposits in a short period of time, which is currently reversing:[3]

PD Market Signal, Sovereign-capped, 1-year PD

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence, As of 4th April 2023. for illustrative purposes only.

PNC & TFC: According to S&P Global research from last year, not only have both PNC and TFC seen a significant increase in the size of their balance sheet since the pandemic started, but the share of HTM securities in the total is also very high (60% and 50% respectively).[4] Even more tellingly, that share rose only after 2021. Effectively, this suggests that PNC’s and TFC’s HTM High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLAs) were bought in the low interest rate environment that, in the absence of BTFP, would have made them very liable to face IR losses if a deposit run-off did materialise.

CFG: CFG saw large moves of deposits from Money Market Deposit Accounts (MMDAs) to Negotiable Order of Withdrawal accounts (NOW) – based on S&P research from last year.[5] MMDAs offer higher interest, but are less liquid than NOW accounts. This indicates that wholesale depositors were keen to have greater freedom to move their deposits quickly, even at the expense of lower deposit rates. That shift in liquidity preference could signal a greater propensity to move deposits out of the bank.

FRC: FRC had been in the news already and reading the reports on share of HTM as a percentage of securities, we see that it had the highest share at close to 90%.

If you are interested in speaking with a credit specialist about Credit Analytics Statistical Models and how to leverage them to automate screening and surveillance in your credit risk management workflow, request a meeting here.

[1] Thanks to this mechanism, U.S. banks can borrow money directly from the Federal Reserve, as opposed to leveraging the interbank market.

[2] 0.5% is approximately the long-term average default rate historically observed in S&P Global Ratings’ rated universe database for companies that move from investment grade to non-investment grade.

[3] “Deposits outflows in Q3 put focus on potential bank funding strains”, S&P Global Market Intelligence, 12 October 2022, available here.

Products & Offerings

Segment