Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Sep 04, 2019

UK recession risks rise as PMI surveys slip into contraction territory in August

- All-sector PMI falls to 49.7 in August, consistent with GDP decline of 0.1%

- Falling manufacturing and construction output joined by near-stagnant service sector

- Business optimism and new orders deteriorate

- Employment stalls, while selling prices rise at slower rate despite higher costs

The likelihood of the UK falling into recession has increased after PMI surveys indicated a contraction of business activity in August. Jobs growth stalled as business confidence regarding the year-ahead outlook deteriorated sharply amid escalating Brexit worries.

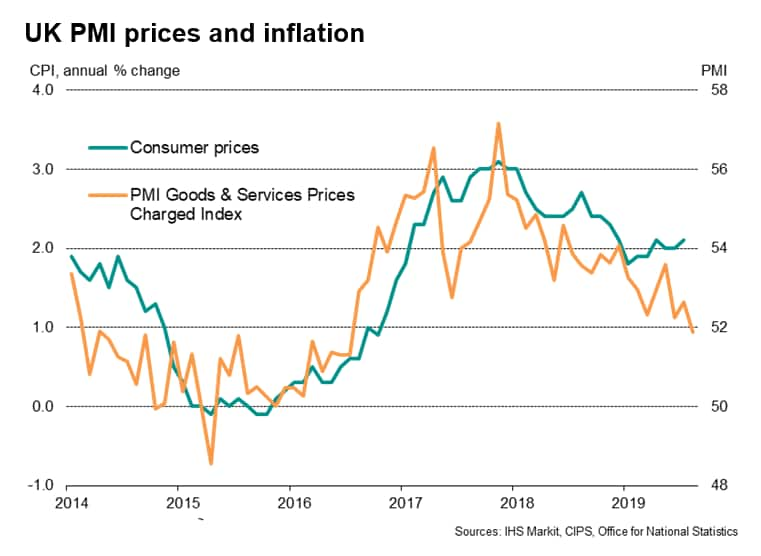

The survey also indicated that companies' margins are being squeezed via price competition, as selling prices rose at the slowest rate for over three years despite costs rising sharply due to the falling pound.

Economy in worst spell since 2009

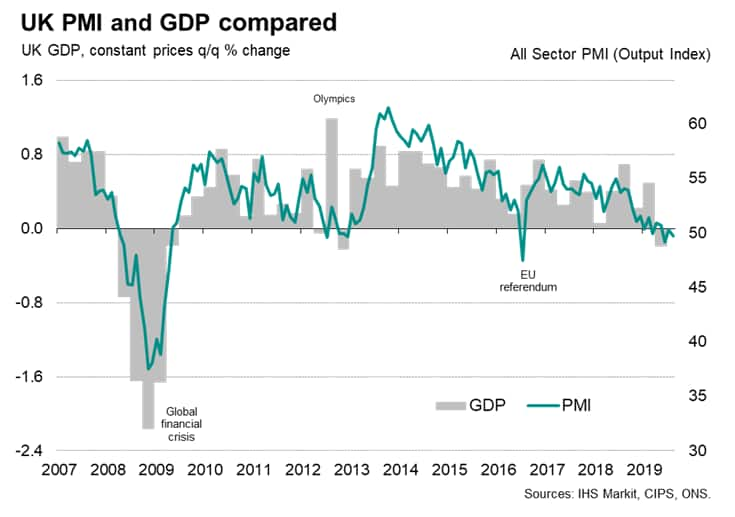

The seasonally adjusted IHS Markit/CIPS 'all-sector' PMI fell from 50.3 in July to 49.7 in August, dropping marginally below the no-change level of 50 to indicate the second decline in business activity over the past three months. The drop pushes the average PMI reading over the past three months to the lowest since the depths of the global financial crisis in mid-2009.

Furthermore, taken together the July and August PMI readings indicate a 0.1% rate of GDP decline, putting economic output on course to fall over the third quarter. With GDP having already declined 0.2% in the second quarter, any further contraction would constitute a technical recession, albeit only mild.

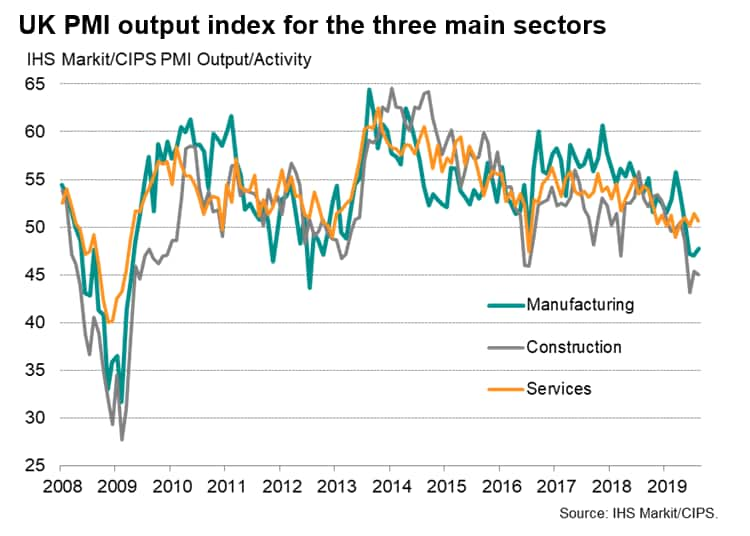

However, the overall picture of only mild decline masks severe downturns in manufacturing and construction sectors, where output continued to fall at rates among the fastest since 2012 and 2009 respectively to suggest both sectors will have contracted sharply again in the third quarter, pushing both sectors into recessions.

Only the service sector remained in expansion, but even here growth almost stalled. So far this year the services economy has reported its worst performance since 2008, with particular weakness seen in transport, financial services, hotels and restaurants, and business-to-business services.

Forward-looking indicators turn lower

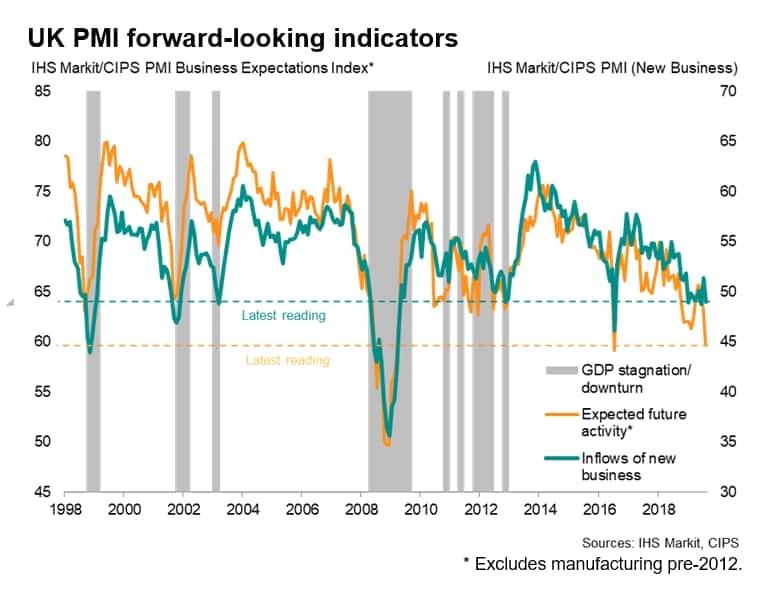

Forward-looking indicators continue to hint at the malaise persisting or even intensifying in coming months.

Inflows of new orders fell for the sixth time this year in August, dropping at one of the steepest rates seen over the past decade. A slowdown in service sector new business to only a marginal rate of increase was joined by steepening rates of loss of orders in manufacturing and construction, which saw the sharpest drops in demand for seven and ten years respectively.

Despite sterling's renewed depreciation, export orders fell especially steeply, declining at the fastest rate since comparable data first became available five years ago, led by an increased rate of loss of goods exports. Companies blamed weak overseas demand, Brexit uncertainty and EU customers shifting supply chains away from the UK.

August also saw a marked deterioration of optimism about the business outlook. Businesses' expectations of their output growth in the year ahead slumped to a level that, with the exception of the low seen in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 referendum, points to the gloomiest outlook since 2009. Business worries continued to centre on Brexit-related uncertainty, as well as more broader fears regarding the prospect of slower economic growth at home and abroad, often in turn linked to geopolitical tensions and trade wars.

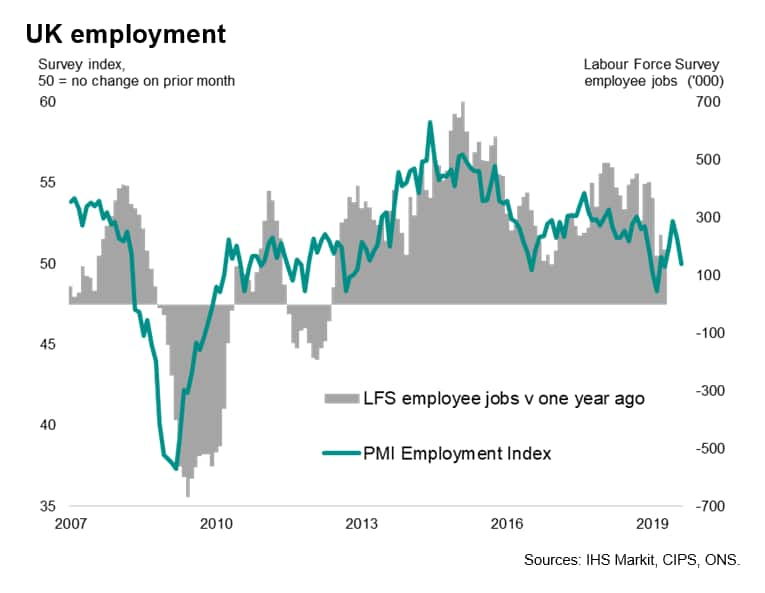

Employment stalls

Jobs growth meanwhile ground to a halt as worries about deteriorating order books and the gloomier outlook took their toll on firms' appetite to hire. Job losses in manufacturing and construction were offset by a marginal rise in service sector jobs, through even the latter was one of the smallest gains seen over the past seven years.

Selling price inflation at three-year low

While the weakened exchange rate showed few signs of helping boost exports, the detrimental impact of the drop in the value of the pound was seen in terms of import prices, with companies widely reporting that higher costs of goods from abroad had contributed to the sharpest rise in input costs for four months.

Despite the accelerated rise in costs, average prices charged for goods and services showed the smallest monthly increase since July 2016, primarily linked to companies reporting the need to offer discounts to stimulate sales in the face of weakened demand.

Looser policy bias

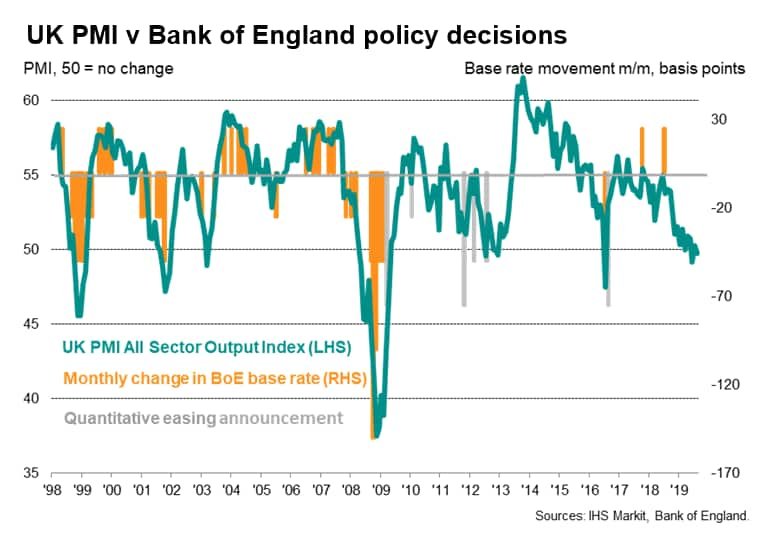

The August decline in the all-sector PM has pushed the surveys further into territory that would normally be associated with looser monetary policy. Such weak PMI readings have in fact never been seen before in over 20 years of history in the absence of either recent or imminent stimulus such as rate cuts or quantitative easing.

Our view is that, even if a no-deal Brexit is avoided, the uncertainty relating to the UK's trading position with the EU will spill into 2020, dampening demand, exports and investment. The risks are therefore tilted to the downside. We therefore remain unconvinced that the Bank of England will be in any position to hike interest rates at least until 2021, and the deteriorating data flow raises the possibility that, whatever happens in terms of Brexit, the next interest rate could be a cut.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS

Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2019, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-recession-risks-rise-as-pmi-surveys-slip-into-contraction-040919.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-recession-risks-rise-as-pmi-surveys-slip-into-contraction-040919.html&text=UK+recession+risks+rise+as+PMI+surveys+slip+into+contraction+territory+in+August+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-recession-risks-rise-as-pmi-surveys-slip-into-contraction-040919.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=UK recession risks rise as PMI surveys slip into contraction territory in August | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-recession-risks-rise-as-pmi-surveys-slip-into-contraction-040919.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=UK+recession+risks+rise+as+PMI+surveys+slip+into+contraction+territory+in+August+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fuk-recession-risks-rise-as-pmi-surveys-slip-into-contraction-040919.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}