Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Jan 03, 2022

As predicted, the global financial sector largely avoided major crises in 2021 (Lebanon standing out as the key exception). For 2022, risks and uncertainty remain heightened. The sizeable support measures introduced early in the pandemic are largely being phased out or have already been removed. Against a background of tightening global monetary policy and high inflation, alongside new COVID-19-related uncertainties, 2022 will test how successful these measures truly were - if they prevented businesses from failing or just delayed recognition of new non-performing loans.

1. Although liquidity conditions will remain loose by historical standards, rising inflation in many emerging markets and less-expansive monetary policy in advanced economies will raise funding costs.

At least 19 emerging market economies raised policy rates in 2021 and the overall policy direction is moving towards a global rate-tightening phase. Although well-communicated forward guidance should prevent major "taper tantrums", tighter liquidity will encourage investors to adjust risk pricing. This will raise borrowing costs for emerging market sovereign and bank borrowers, with more selective demand generally for higher-risk and long-duration assets throughout 2022. Many developing markets will also need to raise rates to defend their exchange rates, especially in economies with high fiscal deficits and those susceptible to currency fluctuations such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Singapore, Brazil, Argentina, and Indonesia taking some steam out of credit growth in those markets.

2. Trends in lending rates will vary, and in many cases be based on regional factors.

In 2022, rising interest rates and a more cautious stance by regulators towards household borrowing are likely to slow credit growth, although we expect it to remain higher than pre-pandemic rates across the globe and in nearly every region. So far, regulators in Europe have taken the most aggressive stance to contain household lending, with Bulgaria, Czechia, Norway, Romania, and Sweden phasing in higher countercyclical capital buffers from mid-to-late 2022. These and similar measures elsewhere should lower credit growth in Emerging Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States next year. By contrast, Latin America, which was the only region to record slower credit growth in both 2020 and 2021 versus the pre-pandemic period, should experience a strong rebound in credit growth in 2022, in part because of higher inflation.

3. Sovereign exposures are likely to continue growing in emerging markets, increasing bank-sovereign linkages.

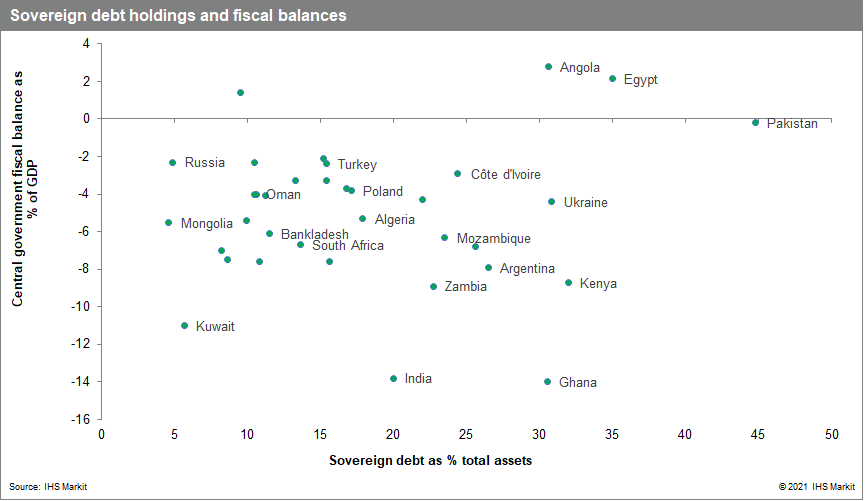

Delays in fiscal consolidation, especially in the Sub-Saharan Africa region, raise concerns for private-sector credit recovery and increase bank-sovereign linkages. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many banks globally diverted more of their portfolios towards the perceived safety of liquid public assets or expanded holdings in response to higher supply. This was particularly the case in Sub-Saharan Africa, where bank holdings of sovereign debt grew 23% in 2021. Economies likely to record sizeable central government deficits and where banks are most likely to increase their holdings of sovereign debt - thus increasing their exposure to sovereign risks - include Ghana, India, Zambia, Kenya, Argentina, and Mozambique.

4. Corporate debt is likely to remain a threat to asset quality, but recent improvements in corporate gearing are encouraging ahead of broader interest-rate increases.

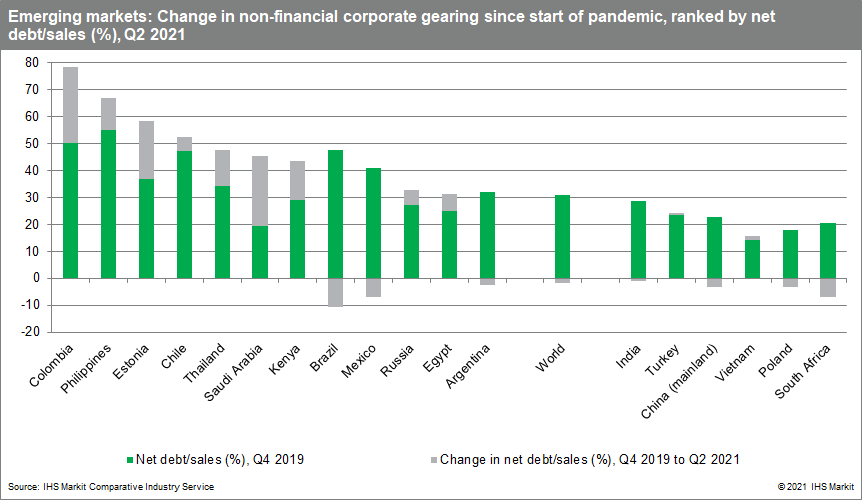

Global non-financial corporate gearing, as measured by net debt to sales, has trended down since the onset of the pandemic as companies undertook more cautious financial positioning. This applies in much of the developed world, including the United States, Canada, the European Union, Australia, and Japan. Nevertheless, overall debt levels remain high, and emerging markets present a more mixed perspective. Mainland China, India, Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa all reduced non-financial corporate gearing. Economies where companies assumed more debt relative to sales are concentrated in the Middle East and South-East Asia, namely Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the Philippines, and Thailand, signaling the potential for rising NPLs as debt service costs rise, global growth slows, and commodity prices cool. Colombia experienced the fastest growth of corporate debt within those emerging markets IHS Markit experts have reviewed, largely because of increased financial stress across multiple industries including airlines, energy, materials, construction, utilities, and media and entertainment.

5. Non-performing loans could edge up but an NPL tsunami is unlikely.

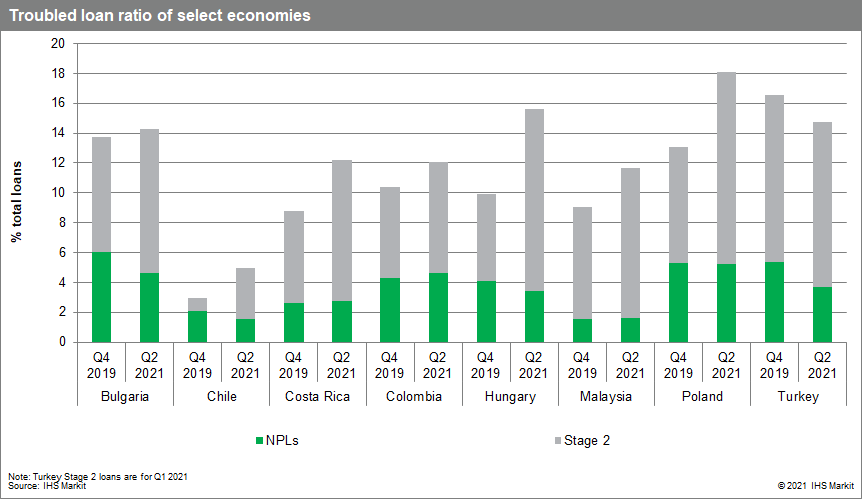

Forbearance and policy support measures have worked effectively so far. NPLs are estimated to have edged up marginally in 2021 but remain below pre-pandemic averages globally. The bulk of loan-payment moratoriums have now expired, although many only in late 2021, and as a result, we expect NPLs will edge up over 2022. However, faster than originally anticipated recoveries from the pandemic and encouraging data on the performance of loans that benefited from COVID-19-related support measures in many economies suggest that new defaults will be modest. Significant downside risks to this outlook exist in several economies, notably where Stage 2 loans remain elevated despite low NPLs (such as Turkey), where restructured loans account for an outsized portion of the loan book (Dominican Republic, Panama, and Peru), and where forbearance is likely to extend further and potentially mask true asset quality (Mongolia and Ukraine).

6. Broad-based support measures will be replaced with targeted support for priority sectors, particularly micro, small, and medium-sized enterprise (MSME) loans.

Although broad-based support measures will be rolled back, governments and authorities will continue to prioritize funding to strategic and important sectors, particularly small enterprises, to alleviate poverty, boost employment, and reduce the potential for social unrest. With borrower history still lacking in many emerging markets, banks themselves will remain reluctant to lend to MSMEs without added incentives. In some markets we expect international development agency-funded programs (Uzbekistan) and government credit guarantees to boost funding for MSMEs without significantly increasing risks to bank balance sheets. In others, such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia, banks will continue to boost lending to small and medium-sized enterprises to meet existing lending quotas. As banks expand MSME lending, overall NPL ratios will edge up in economies without significant credit guarantee programs in place as historically MSME impairment is higher than for the wider loan book.

7. Profitability will continue improving, but gradually.

Through the second half of 2021, multiple banking sectors have achieved a slow improvement in profitability ratios after the sharp decline observed in 2020 and early 2021. Most of this improvement has been led by reduced provisioning needs - which lowered costs - alongside higher interest rates and faster levels of credit growth, which raised overall income. Profitability ratios remain low by historical standards, however, and even with the recent improvement, they are still below pre-pandemic levels. We expect profitability ratios to improve gradually through 2022, particularly if provisioning needs remain low and rising interest rates improve net interest margins.

8. If a new shock, epidemiological or other, does occur, policymakers in emerging markets will respond, but measures will be less robust.

During 2020, most central banks, regulators, and governments reacted forcefully in response to the pandemic, instituting multiple measures including forbearances, credit guarantees, and liquidity support. While these measures helped banking sectors to contain the largest proportion of the COVID-19 shock, they induced additional costs to governments, led to looser standards of lending, and allowed some very weak borrowers to continue consuming resources. In 2022, governments will likely favor much smaller and more targeted measures that will likely place greater burdens on private-sector participants.

9. Expansion of sustainable finance products and further refinement of "green" policies for the financial sector will be a growing policy priority.

While overall policy will remain focused on post-pandemic recovery management, "greening" of the global financial sector will be a growing focus of central banks and policymakers in 2022. Although some banks have introduced their own green mortgage strategies and have successfully placed green bonds to finance climate-friendly projects, international pressure has continued to build for more formal action. We expect the European Commission to take the lead on facilitating the provision of green financing and lending in the coming year, setting a standard and paving the way for other regions to develop and formalize green initiatives.

10. Consolidation is likely to continue and could accelerate in key economies.

Larger banks will continue to focus more on gaining market share in priority markets and less on maintaining a broad geographic footprint, divesting non-strategic units. Small banks will seek to consolidate into larger and stronger entities through mergers and acquisitions. Consolidation in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly across borders, will expand the position of pan-African banks while pre-existing profitability pressures in Europe will continue driving consolidation there. Recent regulatory loosening relating to mergers and acquisitions in the Philippines, the inclusion of all banks in mainland Chinese stress tests, calls for an asset quality review in Mongolia, and ongoing distress in Lebanon are likely to drive the merger or closure of smaller and weaker banks in these economies as well.

Posted 03 January 2022 by Alyssa Grzelak, Director, Banking Risk, S&P Global Market Intelligence