Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY

Apr 04, 2022

PMI at 18-month low as manufacturing disrupted by Ukraine war and Omicron wave

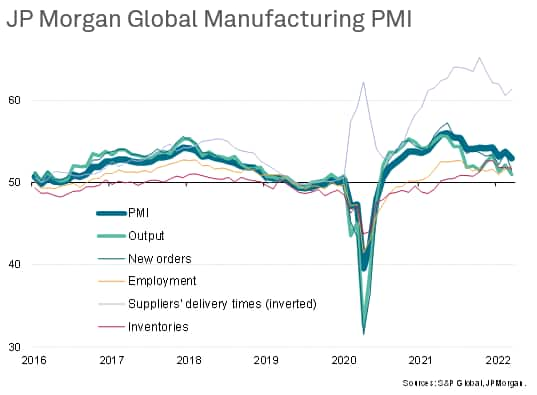

The JPMorgan Manufacturing Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™), compiled by S&P Global, fell from 53.7 in February to a one-and-a-half year low of 53.0 in March. Production and demand growth was subdued by a combination of headwinds, including the Ukraine war and new COVID-19 related disruptions - notably in China. These headwinds led to an intensification of supply chain delays and re-acceleration of price pressures, as well as a renewed fall in global trade flows. Business confidence also fell sharply, down to the lowest since September 2020, signalling downside risks to output growth in the second quarter.

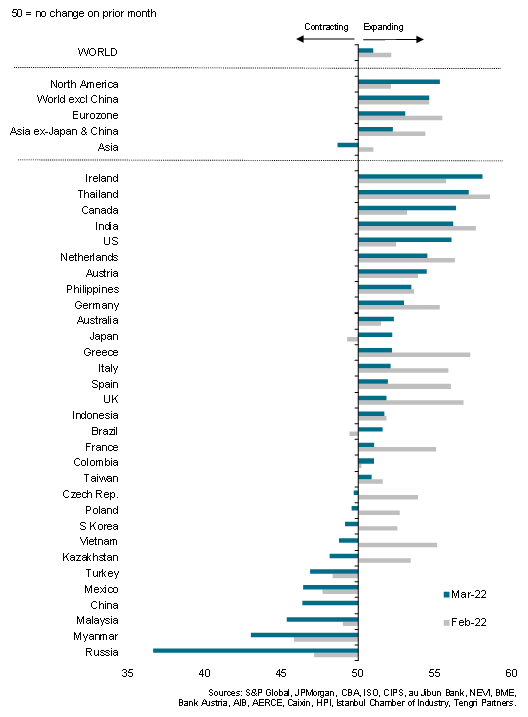

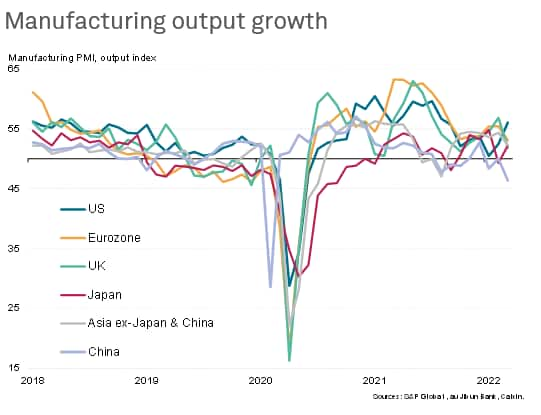

However, trends varied markedly around the world. Improved manufacturing performances in the US and Canada, linked in part to signs of the supply squeeze easing, contrasted with a deteriorating picture in Europe due to the war and in Asia due to the Omicron wave.

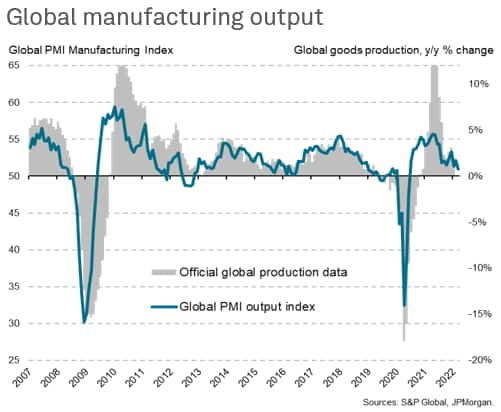

Output growth slowest since July 2020

Global manufacturing production growth slowed in March to the weakest seen so far in the recovery from the first pandemic lockdowns in 2020. The slowdown was led by the steepest collapse in Russian production since May 2020. Excluding the pandemic disruptions, the decline was the most severe recorded in Russia since the global financial crisis in 2008-9. However, output also fell in mainland China, dropping at the sharpest pace since February 2020, amid new COVID-19 lockdowns.

Output also notably fell back into decline in South Korea and Vietnam due to the Omicron wave, with deepening contractions seen in Malaysia and Myanmar and slower expansions recorded in Taiwan and India, all of which contributed to the weakest production gain across Asia ex-China and Japan since last September, when production was hit by the Delta wave.

There was better news in North America, where output rose in the US at the sharpest rate since last August and production in Canada grew at a pace not beaten for a year. Mexico bucked the trend, however, with an increased rate of contraction.

In Europe, the Ukraine war took a toll on production growth, most prominently leading to renewed falls in output in Poland and the Czech Republic, as well as deepening the downturn in Turkey. However, eurozone and UK growth also slowed, with the former seeing the slowest upturn in output for 21 months, dampened by the impact of the war and, in the case of the UK, ongoing Brexit-related factors. In contrast, Ireland, benefitting from Brexit, led the global upturn in March.

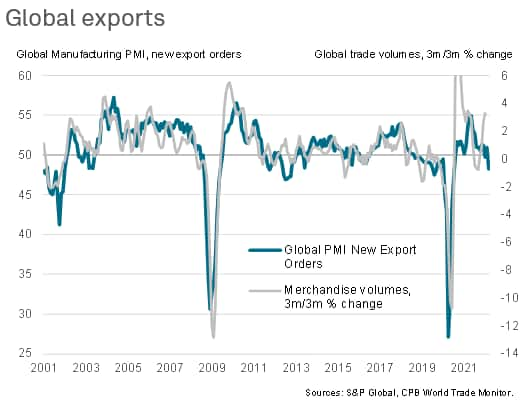

Global trade back in decline

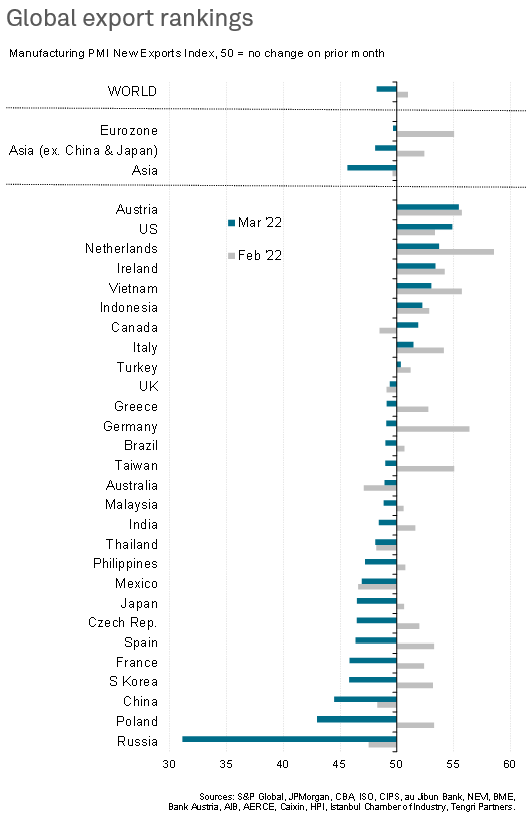

March also saw global export orders fall back into decline after a brief recovery in February, with the rate of deterioration the fastest since July 2020 due primarily to the combined impact of the Ukraine war and disruptions caused by the Omicron wave.

Only nine of the 28 economies covered by the PMI reported higher exports, led by Austria, the US, the Netherlands and Ireland. By far the steepest reduction was seen in Russia, though an accelerating decline was recorded in China and renewed falls were seen in Japan, the rest of Asia as a whole, the eurozone and Brazil, as well as in the eastern European countries covered by the PMI

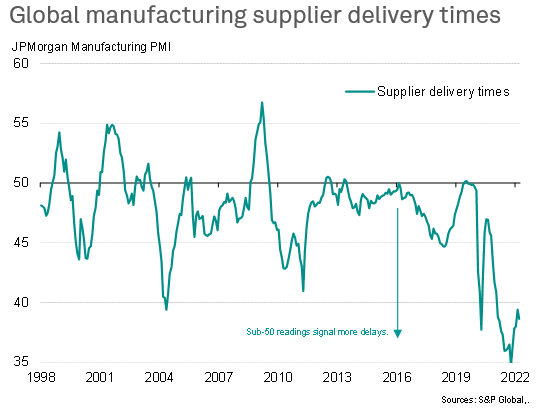

Supply delays worsen

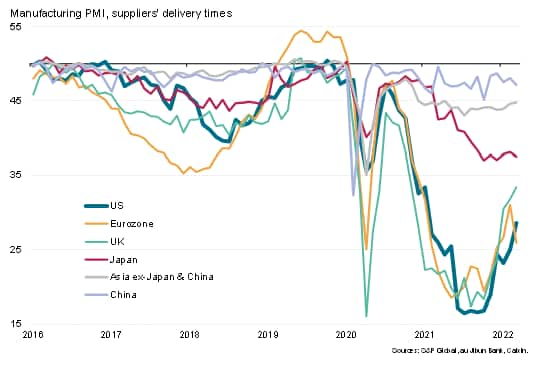

An additional impact from the Omicron wave in Asia and the war in Europe was a worsening of global supply chains. Average supplier delivery times reported by manufacturers lengthened to an increased extent in March, albeit with the incidence of delays remaining below the all-time highs seen in 2021.

There was a marked variation in supplier delays by region, however. The worsening of the supply situation was focused on Europe - and the eurozone in particular - due to the war. However, lead-times also lengthened to slightly greater degrees in Japan and China, albeit remaining far less widely reported than in the US and Europe. In contrast, an encouraging easing in the degree of supply chain tightening was recorded in the US and the UK, which saw the incidence of delays fall to 14- and 17-month lows respectively, thanks in part to the easing of shipping and other logistical issues.

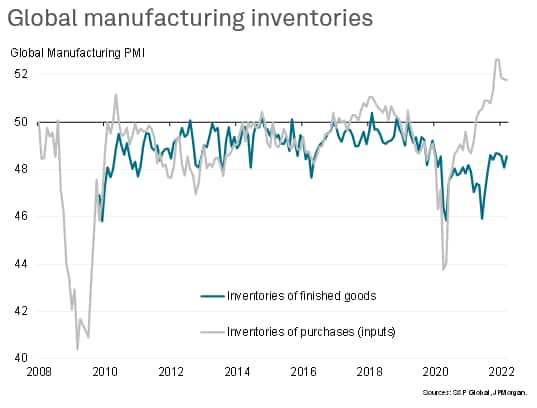

Stocks of goods for customers depleted further, but inventories of inputs rise sharply

The ongoing widespread nature of the supply chain crisis continued to affect inventories. First, curbed production capabilities resulting from shortages of certain key raw materials, notably semiconductors, as well as labour shortages, resulted in yet another steep drop in manufacturers' inventories of finished goods.

Second, manufacturers sought to boost inventories of other raw materials and components where supply permitted, often citing a desire to build additional safety stocks as a precaution against future potential supply disruptions. The incidence of input buying for safety stocks rose to the highest in the survey history. Although inventories of purchased inputs rose at a slower rate than the peaks seen in 2021, the rate of stock building remained among the quickest seen over the survey's quarter of a century history.

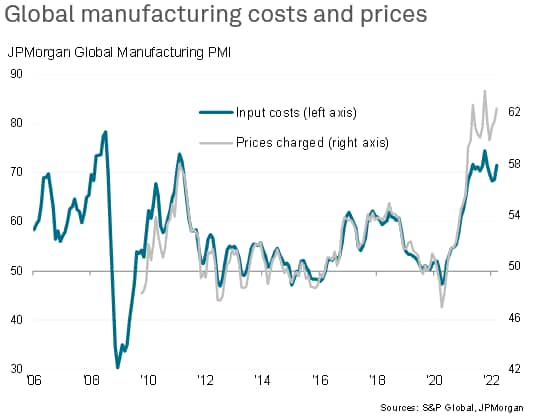

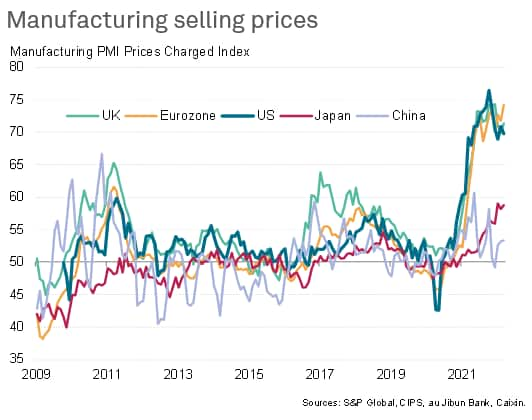

Inflation rates accelerate, led by surge in eurozone prices

The worsening supply situation and surge in energy prices associated with the Ukraine invasion meanwhile led to a further intensification of inflationary pressures. Average material input price inflation rose to the highest since last November while average selling price inflation hit the highest since last October's record, the latter buoyed not only by the rising raw material price increases but also buoyed by rising wage pressures.

Rates of inflation for goods leaving the factory gate were again highest where the supply crisis has been most keenly felt, namely the US and Europe. However, whereas the slight easing of supply pressures took some heat out of the rate of inflation in the US, the worsening supply crisis in Europe pushed prices up at an unprecedented rate in March.

Price pressures remained more muted in Asia, though both China and Japan saw increased rates of inflation, the latter close to January's multi-year high.

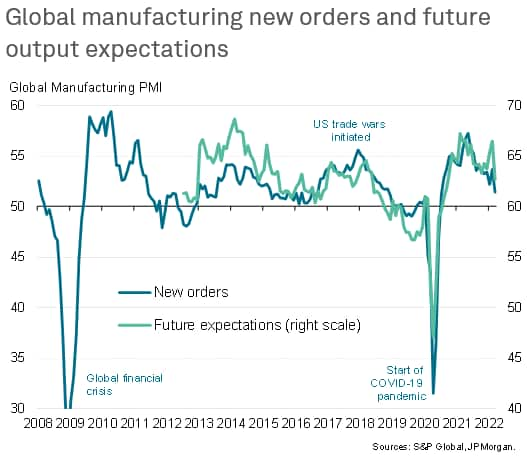

Forward-looking indicators deteriorate

The forward-looking indicators from the survey suggest that output growth could weaken further as we move into the second quarter.

First, the drop in exports recorded during the month added to a broader weakening of demand, which in turn resulted in the rate of growth of new orders slowing globally to the lowest since July 2020, rising at only a very modest pace. Although growth of new orders accelerated in the US and Canada, the UK reported only a modest increase and growth slowed to a 21-month low in the eurozone. Steep falls were recorded in Russia and China, and renewed reductions in eastern Europe, with a marked slowing linked to the Omicron COVID-19 wave also seen in the ASEAN region.

Second, the headwinds of soaring costs - especially for energy - tighter supply lines, cooling demand conditions, the Omicron wave, Russian sanctions and the broader geopolitical uncertainties caused by the Ukraine war led to a marked downshifting of companies' expectations for the coming year. Optimism regarding future output slumped globally to its lowest since September 2020, dropping to an extent not seen prior to the pandemic since comparable data were available a decade ago.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@spglobal.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole

or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-at-18month-low-as-manufacturing-disrupted-by-ukraine-war-and-omicron-wave-apr22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-at-18month-low-as-manufacturing-disrupted-by-ukraine-war-and-omicron-wave-apr22.html&text=PMI+at+18-month+low+as+manufacturing+disrupted+by+Ukraine+war+and+Omicron+wave+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-at-18month-low-as-manufacturing-disrupted-by-ukraine-war-and-omicron-wave-apr22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=PMI at 18-month low as manufacturing disrupted by Ukraine war and Omicron wave | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-at-18month-low-as-manufacturing-disrupted-by-ukraine-war-and-omicron-wave-apr22.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=PMI+at+18-month+low+as+manufacturing+disrupted+by+Ukraine+war+and+Omicron+wave+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fwww.spglobal.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpmi-at-18month-low-as-manufacturing-disrupted-by-ukraine-war-and-omicron-wave-apr22.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}